Speaker series on opioids brings community closer through stories of addiction, hope for recovery

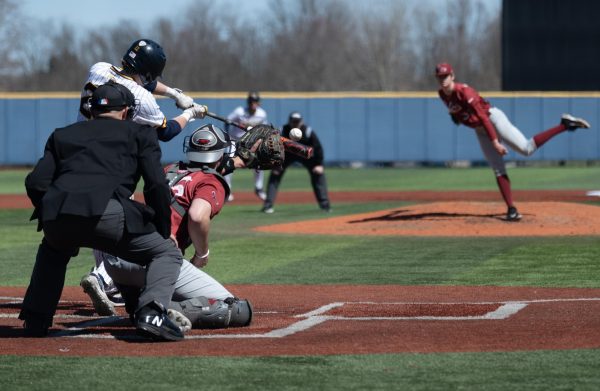

Veteran Josh Vandygriff talks about his time in the Army and his struggles with opioid addiction at the Nonprofit Spotlight Speaker Series event held at Henderson Hall on Thursday, Oct. 18, 2018.

October 19, 2018

Rachel Pike-Lee told the packed room in Henderson Hall on Thursday her family has tried “everything you can imagine” — hospital visits, drug court, Oriana House classes, Veterans Affairs services, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings — to help her brother. She said he is a veteran who struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder, alcoholism and violence.

“When I heard your story, I wanted to pass out because it was so similar, but a different form of addiction. … I just wish your story was my brother’s story,” said the Kent State graduate student studying vocational rehabilitation counseling.

Pike-Lee was talking to Josh Vandygriff, one of the Nonprofit Spotlight Series speakers that evening who told the story of how he served active duty in the Army, how he was deployed to Iraq, how he came home with severe PTSD, how taking pills escalated to heroin, how he almost lost his family to the drug, how he joined the Turning Point Program and, ultimately, how he’s now living in recovery.

Pike-Lee cried and shook as she spoke of her brother. Her father sat beside her, gently patting her with one arm and squeezing a stress ball in the other.

The room cried and shook with her.

The Nonprofit Spotlight Series focused on the opioid epidemic tearing the nation apart. According to a report released by the Ohio Department of Health in September, the state’s unintentional overdose deaths rose from 4,050 in 2016 to 4,854 in 2017.

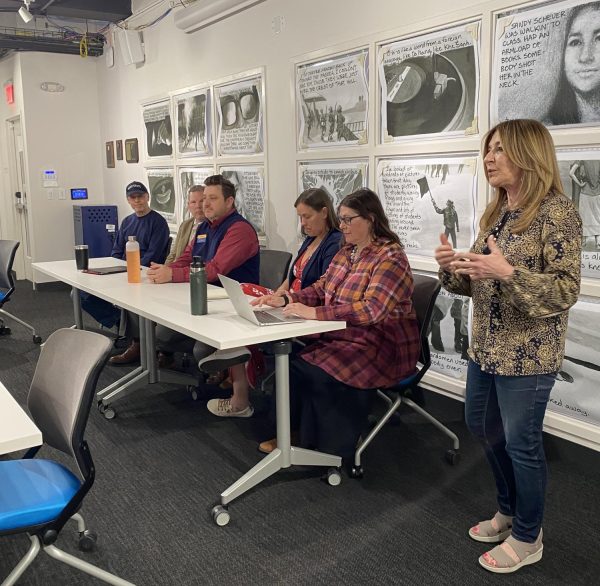

Close to 200 people gathered in the lecture hall to hear the three panelists share their stories, some of their endings happy and some sad.

Travis Bornstein, one of the founders of Hope United — a nonprofit organization serving Portage, Stark and Summit counties that works toward ending the stigma surrounding addiction — told the audience about his son, Tyler, who died of a heroin and fentanyl overdose in 2014 at age 23.

Bornstein and his wife, Shelly, founded Hope United two years later to help other families dealing with addiction. The couple is raising money to build a relapse prevention wellness center — the first in Ohio — which they plan to call Tyler’s Redemption Place.

“Sobriety is a long-term adventure,” Bornstein said. “We’re going to pick up right where traditional treatment leaves off, developing programs for people who just come out of treatment in an outpatient setting, continuing to work with them professionally for the counseling they need, helping them develop the coping skills they need.”

The video Bornstein shared with the audience showed the center will include cryotherapy, a salt cave, massage therapy, weight and cardio rooms, yoga classes and a multi-purpose gym.

Once the project raised $1.4 million, the Bornsteins realized the property they planned to build the center on was too small. The couple originally chose this location because in September 2014, the Summit County Sheriff showed up at the Bornsteins’ front door to tell them a body had been dumped in a vacant lot the night before.

The body was Tyler’s.

When he overdosed, the person he was with didn’t call 911. Instead, he took his lifeless body to the lot.

In October 2017, the Summit County Council donated 10 acres of land to build the center. On Sept. 28 this year, the four-year anniversary of Tyler’s death, there was a groundbreaking ceremony for the center.

Bornstein said part of his mission, which the center will encourage, is showing people to embrace pain.

“Every single person who struggles with mental health or the disease of addiction had some form of trauma in their life, whether that pain is physical pain, emotional pain, mental pain, spiritual pain,” he said.

He urged the audience to start altering conversations about the epidemic. He said too many people view addiction as a choice instead of what it really is — a chronic brain disease.

A recent Ohio Health Issues Poll found six in 10 Ohio residents said addiction is a disease. Three in 10 people surveyed said addiction is not a disease, and 7 percent were uncertain.

Interact for Health, a nonprofit organization that promotes good health in 20 counties around Cincinnati, sponsored the study.

“Until we understand this as a society, we’re never going to solve this problem,” Bornstein said.

Bornstein added older generations focus a lot on the stigma associated with addiction, often sitting on their “judgement seats, judging everybody up.”

“What you guys do a good job of is you have a lot more mercy and grace,” he said, referring to the younger, college-age audience members. “My guess is every one of you know somebody who’s been impacted by this thing, right?”

After almost everyone in the room raised a hand, Bornstein challenged them: “Let’s get the conversation going. Let’s respond with love and compassion. If we do that, I believe we can start changing this thing.”

Thomas Teodosio, a judge from the Akron-based Ninth District Court of Appeals, spoke next. He used to preside over the Summit County Court of Common Pleas’ Turning Point program, a 12-month drug court designed for those struggling with substance abuse.

Teodosio said once people are evaluated for their substance abuse and mental health issues, the drug court sets them up with a treatment plan. The drug court focuses much on rewarding good behavior and provides an immediate sanction to bad behavior.

Teodosio said many of the people who came into his drug court were “no doubt in my mind, the best manipulators in Summit County.” If they were honest with him and admitted to their mistakes, Teodosio would still give a sanction, but it wouldn’t be as severe as someone who lied to him. Consequences included jail time, inpatient treatment and tasks like writing essays and obituaries.

“My goal is not to punish; it’s to provide them a safe environment to move forward,” Teodosio said of the program. “Almost every time that I would take someone into custody, and they’d go kicking and screaming with the deputy and cursing at me sometimes, inevitably, they would come back and say, ‘Judge, I apologize. I realize now that if you hadn’t taken me into custody, I’d probably be dead today.’”

According to Cleveland.com, Common Pleas Court Judge Joy Malek Oldfield, who now presides over the program, said Turning Point “served 439 people with drug and alcohol issues, and 103 people graduated from the program.”

Teodosio then introduced the third speaker, Vandygriff, a graduate of the program. He asked Vandygriff how long he’s kept up his sobriety.

“Five years, five months, four days,” Vandygriff answered. The audience roared in applause.

Vandygriff shared the story of when, a year into his marriage, his wife announced, with a huge smile on her face, she was pregnant. He was a daily heroin user by then, but he hid it well from his family and friends.

“That should’ve been awesome,” he said. “And it was for the first 10 seconds. How the hell am I going to raise a kid when I’m addicted to heroin, smoking pot every night, drinking every night?”

Later, Vandygriff said he was spending so much time at work that he spent $2,200 on a pickup truck for his dealer so he could deliver him his heroin.

On the night before his wife’s scheduled c-section, Vandygriff tried to take his life. He felt the thing that was going to hurt her most was him. A veteran friend kept him on the phone all night until it was time to go to the hospital.

Right after the birth, Vandygriff met his dealer in the parking deck of the hospital. He arrived in the pickup truck, and just as Vandygriff bent down to snort his heroin, a car pulled up beside them — it was his parents, there to meet their granddaughter for the very first time.

Vandygriff sought help and was in recovery for six months before he relapsed. He calls the day he sat in the back of an Akron Police Department car in handcuffs the best day of his life. Drug court saved him, he said.

Vandygriff encouraged the audience members to seek help if they or someone they know are battling with drugs. He added they should lock up prescription drugs at home so visitors don’t have access.

“I just want everybody to know there’s hope,” he said. “There is hope. I wasn’t using to get high; I was using to try to feel normal. … The key to beating addiction is to tell on your own addiction. When you need help, you have to be strong enough to ask for it. Secrets keep you sick.”

Pike-Lee and other audience members lingered after the event, asking Bornstein, Teodosio and Vandygriff for advice on how to talk to people in their own lives who are facing addiction. Vandygriff offered to meet with Pike-Lee’s brother.

Valerie Royzman is the features editor. Contact her at [email protected].