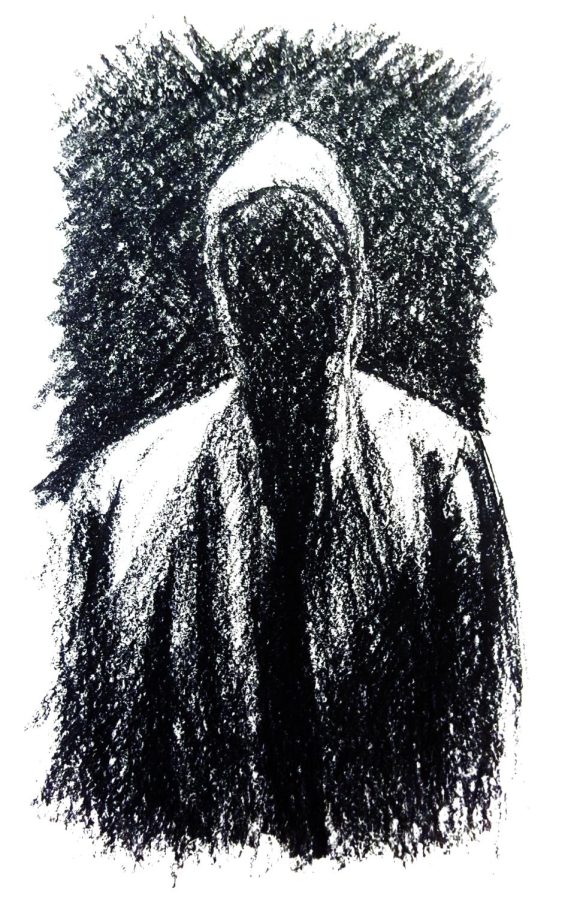

Hoodie. Male. Black: A university alert sparks racial profiling debate

March 14, 2017

On Feb. 24 at around 8:26 p.m., Kent State students, faculty and staff subscribed to Flash ALERTS received a text warning of a robbery on Summit Street near the Kent State Student Recreation and Wellness Center.

Instead of the actual robbery catching people’s attention, the description of the suspect angered members of the community.

Within the text message, the suspect was described as a “black male mid-20s in hoody/jeans.”

No other information was released via Flash ALERTS on the appearance of the suspect.

The description caused some to believe it to be racial profiling, while others only saw it as a way to identify the suspect.

Devon Childress, a freshman digital sciences major and public relations manager for Male Empowerment Network (M.E.N.), felt directly affected by the description.

“I was wearing a hoodie that day, so it could have been me that might have been stopped to be checked,” Childress said. “I didn’t even know what the situation was. I just saw the profiling.”

Childress thought that a description, like the one in the Flash ALERT, didn’t deserve to be sent out.

“If you don’t have a clear description, then there’s no point in putting one out because it’s ineffective because it’s so vague,” Childress said. “It alienates groups of people when you need the community to respond to that alert.”

Ben Smith, a senior applied conflict management major, took to Twitter to express his frustration, responding to Kent State’s tweet about the robbery with “racial profiling is not helpful and stupid.”

Smith was upset to see something he perceived as vague serve as the only clue in the robbery.

“It wasn’t descriptive in any way that was beneficial to finding a suspect,” Smith said. “It was technically a description. However, the only identifiable characteristic was their race. That is inherently racial profiling.”

Smith said he believed the Flash ALERT caused more issues than it was trying to solve.

“The information was a ‘mid-20s black male wearing a hoody and jeans.’ It was like 50 degrees in Ohio; literally everyone was wearing a hoody and jeans,” he said.

Ile-Ife Okantah, a senior journalism major and co-chair of public relations for Black United Students (BUS), was also disappointed to see the description.

“They pretty much just said a black man in clothes,” Okantah said.

Okantah said she believed it to be racial profiling as well.

“I don’t want to put it on the (police) department to say that it was intentional, but a lot of times many microaggressions we deal with are unintentional. I think it was a lack of sensitivity and that it does fall under the category of racial profiling because we are a minority on campus. I think their intent was to narrow it down, but they did it in a way that can be construed as racist,” she said.

However, according to KSUPD Community Resource Officer Tricia Knoles, it’s not the police department that determines the description of the suspect.

“We have to go by the descriptions that the victims or witnesses give us,” Knoles said. “We can’t make up the descriptions because we didn’t see the person, so the witness or victim that saw the person would be the ones giving us the description.”

The Clery Act requires colleges and universities to inform the community of crime occurring in the area in a reasonable amount of time. Before the warning can be made, police must check multiple factors to make sure the alleged crime happened.

After the victim or witness makes the first call to the dispatcher, an officer goes to the scene and speaks with whoever saw the suspect. The officer asks the witness what they remember and then makes sure the suspect isn’t still in the area, Knoles said.

Information that victims have on a suspect vary, especially after a serious crime that could have shocked them. Knoles said she believes this is a reason behind vague descriptions of suspects.

“Victims may or may not remember everything because they just experienced a traumatic event, so sometimes their process is fragmented. Whatever they can remember, the officer lets the dispatcher know that this is all the victim can remember for the description, and they put that out,” Knoles said.

Valerie Callanan, a sociology professor who studied the effects of race, crime and media for over 20 years, does not see the Flash ALERT as targeting a specific race.

“When somebody creates a description like that and the police put it out — it’s a very vague description — but I wouldn’t call that racial profiling because someone saw someone who was black,” Callanan said. “Racial profiling is when police pull people over who fit a certain demographic they have a suspect for. This is not an example of racial profiling insofar that what they did was publish a description.”

Callanan used to perform an experiment on her classes where she would have a graduate assistant of hers randomly interrupt her class, shout an obscenity and run away. She would then have her class describe what the interrupter was wearing or looked like.

“I’d see huge variations. The reality is that we’re not paying too much attention to what the person is wearing and more attention to what’s happening,” she said.

“As human beings, we’re notoriously awful at describing what somebody looks like when there’s this kind of moment. This is exactly the same for victims. You have less time to formulate what that person looks like in your mind because you’re reacting to the event more and trying to figure out how to survive whatever the fear is,” she said.

David Kessler, associate professor of sociology, said he believes that, despite the apparent rush of racially-charged cases within the past few years there hasn’t been an actual increase of these instances.

“What we saw, we didn’t always talk about,” Kessler said. “There were a lot of things we saw but never hit the newspapers until now.”

“You’re seeing more people detecting it and documenting it with video, so we think it’s going up, but no, we’re just exposing what has been there for a long time,” he said.

On April 2, 2014, the Kent State main campus went under lockdown after someone reportedly fired a shot near Bowman Hall and then fled the scene.

The 2014 description mirrored the Feb. 24 alert: a black man wearing gym shorts and carrying a silver handgun.

Traci Easley Williams, senior lecturer of journalism and pan-African studies, recalled the moment the warning was sent out.

“I was with students, and I personally dropped them off at their homes because they were scared to walk on this campus, and that’s ridiculous,” Williams said. “I will always remember the look on my African-American students’ faces when they were so terrified to walk out of the building they’re taking classes in just to walk to their dorms.”

Williams was out of town when the Feb. 24 alert was sent, but she was upset to hear that a similar event to 2014 happened again.

“I immediately saw my students’ faces, and I felt it in my stomach,” she said. “Especially since I have a son, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘Wow, am I going to send my son to a place where he does not feel safe with the people who are supposed to protect him?’”

Williams doesn’t necessarily believe the descriptions to have been intentionally insensitive, but that they were “descriptions of ignorance put out by people not understanding basic cultural competence.”

While she doesn’t approve of the current methods of alerting the Kent State community, Williams does believe there are ways for it to be done correctly and safely.

“We have to protect our students. If there is a crime on this campus, yes, we should be notified. But we should be careful with how to notify people because in the racial climate that we’re in today, things are not getting better,” she said.

In response to those who believe the description of the robbery suspect was racial profiling, Knoles said:

“We put out information as we receive it for the safety of our community. Regardless of what the witness or victim says: black male, white male, female – they give us the description.”

“We are more concerned with the safety of our community. We want to make sure that our community is safe, so we are going to put that description out,” she said.

McKenna Corson is a diversity reporter, contact her at [email protected].