Sochi Olympics audit finds inequality in games

November 3, 2015

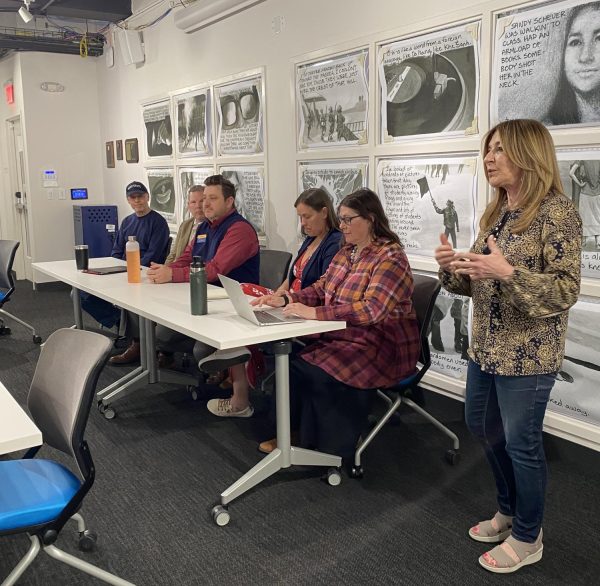

Kent State researchers recently found that the 2014 Sochi Olympics saw a decline in female participants.

The research, conducted by Kent State Researcher Michele K. Donnelly and University of Toronto researchers Mark Norman and Peter Donnelly, was entitled,“The Sochi 2014 Olympics: A Gender Equality Audit,” and found that the Winter Games were the first since 1988 to see a decline in female representation, with just over a 40 percent participation rate in 2014.

The research continued the work of a 2012 paper, also by Donnelly and counterparts, which was an audit of the 2012 London Olympics.

The goal of the papers is to observe the differences in men’s and women’s sports, and to assess “what’s left to do” to promote gender equality in the Olympics. The team found the study’s value in both awareness and global importance.

“Sports are such a large part of society, whether we realize it or not,” Donnelly said. “Success in the game can influence heavily the way countries fund their athletes.”

Norman, a professor at University of Toronto, contributed to the study for the first time this year after observing the research work and results of 2012’s audit.

“The goal going forward is to continue to do these reports at the Olympics and other international sports games,” he said. “Sports are very visible. They serve to highlight and amplify lots of trends that are happening in society, including in gender.”

The paper looked at all 98 events at the Sochi Olympics to determine differences in “rules and structures” in the events. Sections ranged from uniform differences, such as required gender specific costuming in Ice Dancing to differing competing venues.

The study found that although the 2014 Olympics have been the latest in a succession of increasingly equal games, there are still many large disparities between men’s and women’s opportunities and experience in the competition.

Interesting results supporting the conclusion included that 7.1 percent of the events were gender exclusive, all of them “men-only,” and that there are no women at all competing in the Nordic Combined, the last sport not to feature any female competitors.

The study concluded that only 14.3 percent of the events at the games could be considered truly equal.

The ultimate hope of those who conducted the audit is for an equalized Olympics. However, sports are one of the last remaining areas in which a “separate but equal” approach can be taken seriously.

“It’s such a complex problem. I don’t think it can be solved overnight,” Donnelly said.

“I’m not optimistic that we’ll see complete equality in the near future. What I would hope, though, is that reports like this and other prominent voices will continue to advocate for a greater awareness of gender equality and work towards creating that change,” Norman said.

While acknowledging that Sochi took positive steps in adding a women’s ski jump competition for the first time, the paper also included recommendations toward further equality in the form of two main goals: equalizing the number of men’s and women’s events, and equalizing the number of male and female competitors.

Donnelly hopes that the audit can help refocus the public’s lens on gender issues in the games and as a societal whole. She acknowledges that progress has been made, but during progress, we tend to lose sight of what is left to reach.

“There was so much celebration (in the 2012 Games), which was warranted. There were really huge achievements. But that celebration needed to be talked about in a larger context,” she said. “Adding women’s events is a great step, but when only a handful of women are competing, that isn’t a problem solved.”

Cameron Gorman is a General Assignment reporter for The Kent Stater. Contact her at [email protected].