KSU professor’s research says “acting white” accusations cause anxiety

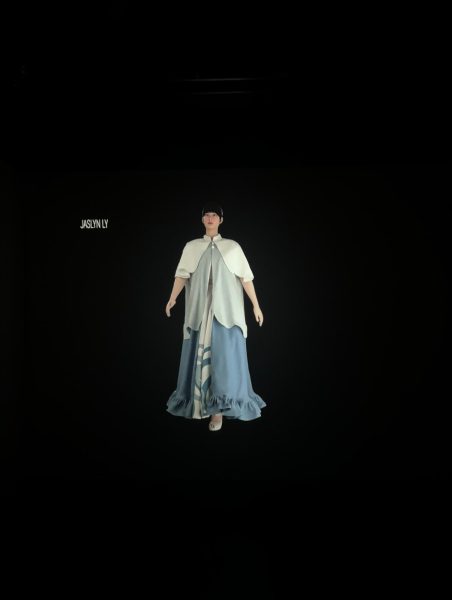

Avery Bounds, a sophomore entrepreneurship major, standing in Oscar Ritchie Hall on Sept. 6. Bounds feels as though the phrasing and bullying should be taken seriously and avoided and has personally encountered it in her life. Photo by Jacob Byk.

September 12, 2012

“Acting white” is a negative accusation African-Americans face that can lead to social anxiety later on in life, according to research done by Kent State University psychology students.

In a study published in the May 2012 issue of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders, KSU researchers found that receiving the accusation of “acting white” can create distress in some African-American adolescents.

The study, led by 2011 KSU doctoral graduate Marsheena Murray, surveyed 110 low-income adolescents from predominantly African-American high schools who completed questionnaires measuring anxiety. Angela Neal Barnett, a Kent State psychology professor who has studied black anxiety disorders for over 25 years, supervised the study.

“Kids who had faced the accusation frequently were more anxious than kids who had heard it once,” Neal-Barnett said. “It’s just that their definition of being black is different from the person making the accusation’s definition. So that can create anxiety if your identity is being attacked.”

Neal-Barnett has also studied the issue pertaining to college campuses, she said, and although the characteristics of “acting white” are different, the accusation can make college campuses an uninviting place for some African-American students.

People who make the accusation are usually making a joke or are jealous of the other person, she said.

“If you don’t fit the criteria, you get the accusation and get somewhat pushed away or pressured to be like the rest of us in college,” Neal-Barnett said. “They see the other person receive high accolades from a professor, and they think they can’t achieve it because they are looked on as a stereotype.”

Neal-Barnett said one of her undergraduate students, 2011 grad Brittney Williams, studied black students on college campuses who make the accusation for her honors thesis. She found that when asked about making the accusation, people felt ashamed for doing so yet knew it was harmful in the first place.

“While people are quick to make the accusation, they express great discomfort in talking about their reasons for making the accusation,” Neal-Barnett said.

She said the basis for both studies came from her research working with African-American adults who had social anxiety. She said many of them could trace their anxiety to an incident in high school or middle school when they first began to receive the accusation they were “acting white.”

Scott Campana, a sophomore history major, said he received the accusation but felt it hadn’t caused anxiety in his life. His junior high friend, however, was a different story.

“They were expecting him to fit this mold,” Campana said about his friend who received the accusation. “He felt he had to act a certain way and that gave him anxiety. Now that he is in college and I know him better, it affected him a lot.”

Avery Bounds, a sophomore entrepreneurship major, said she also received the accusation and was “hurt” at what others thought was a joke.

“Both black and white people will be like, ‘who are you kidding, you’re not really black,” Bounds said. “It means more than you think it does. I shouldn’t have to live up to a stereotype of being black.”

Immanni Golphin, a freshman education major, said she has accused people of the accusation but didn’t mean it.

“It’s rude,” Golphin said. “You can’t act a color. If they’re raised a certain way and raised to be proper, that’s just how they are.”

Contact Madeleine Winer at [email protected].