Liquid Crystal Institute explores improved food safety technology

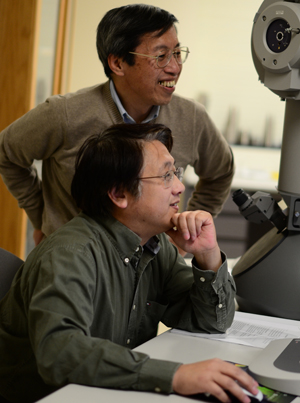

Qi-Huo Wei, associate professor of nano-biotechnology, examines the specimen in a microscope powerful enough to view a single atom, while Hiroshiv Yokoyama, director of the Liquid Crystals Institute, assists from over his shoulder. Photo by Jacob Byk.

January 12, 2012

Kent State’s Liquid Crystal Institute works to break through scientific barriers and most recently, pathogen detection in food and solar energy conversion.

Last July, Hiroshi Yokoyama was promoted to director of the institute, replacing Oleg Lavrentovich, and has since been working with graduate students and research associates to explore new possibilities of liquid crystal technology.

Previously, pathogen detection in food was a lengthy process that could lead to lower safety standards; however, given that the liquid crystals are extremely sensitive to external stimuli, researchers have an opportunity to develop ultra-sensitive sensors, which can make the process of finding pathogens in food much more efficient and straightforward.

Crystal Diagnostics, Inc., a start-up company using the LCI’s technology, recently launched an ultra-fast pathogen sensor system that will expedite the assessing of food quality. This is only one of many possibilities that the technology has in store.

“This application is just emerging and will create another surge of liquid crystal technology in (the) health care industry by providing fast, small, inexpensive real time monitoring devices. This makes the idea of personalized care a reality,” Yokoyama said. “The sensor can also detect E. coli contamination of food in half an hour. This is small and cheap and should be a competitive alternative to conventional detection method.”

In essence, this technology means hospitals can afford to give their patients personalized care that was not previously an option. It also makes for food that is cleaner at a lower cost and higher production rate.

The institute is also turning a focus to solar energy conversion, which could contribute a great deal to green technology opportunities. President Lester Lefton allocated what may be more than $1.5 million to fund research into organic photovoltaics, or the technology for solar energy conversion using organic materials.

“These investments in people and facilities will buoy all research and development activities in the Kent State liquid crystal community,” Lefton said in a press release.

Yokoyama plans to diversify and sharpen the institute’s goals and research as a result of a fast-paced and an already diversifying scientific climate.

“I plan to reestablish the facility infrastructure so that the LCI can serve a larger research community in Northeast Ohio, in collaboration with local industry and academic institutions, in such a way as to create a synergy in this area’s competitive domain of health care, sensors, polymers and liquid crystals,” Yokoyama said.

Contact Christina Suttles at [email protected].