Composing from Cairo to Kent

March 4, 2008

At 87, Halim El-Dabh continues to teach students, and the world, to see beyond the music

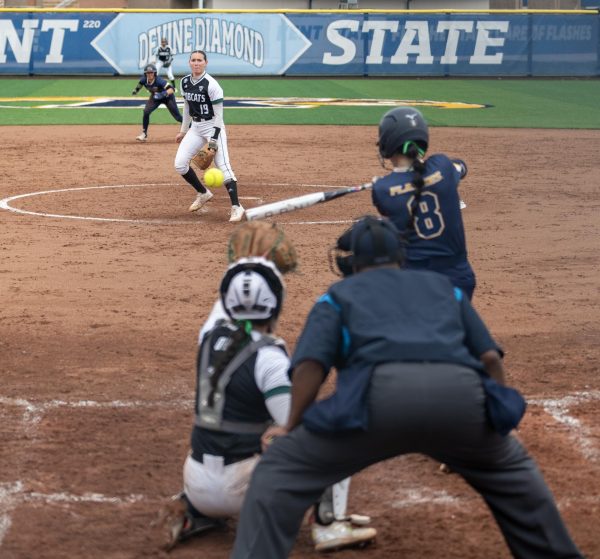

Pan-African Studies Emeritus professor Halim El-Dabh discusses a native dance with his class.

DANIEL OWEN | DAILY KENT STATER

Credit: Ron Soltys

Halim El-Dabh smiles as he sings and dances along with the students in his African Culture Expressions class.

“Where are your voices?” he asks. “You guys are dying.”

With El-Dabh’s encouragement, the students in the class pick up their energy. They are performing a ceremonial Southern Ethiopian dance. But what they are doing is more than just dance, their instructor tells them.

“Your body is a gesture,” El-Dabh says. “The way you walk, move and sit tells about your history.”

El-Dabh, university professor in music, turns 87 today. He was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1921, where his own history began — the history that would lead him to become one of Egypt’s most well-known composers.

Young beginnings

El-Dabh admits to always being on the go as a young boy.

“Even when I was five,” he said, “I always wanted to listen to the radio and dance around. My mom would say, ‘Boy, settle down.'”

But he was first thrust into the musical world when he was 11, and the king of Egypt invited composers from all over the world to come to Cairo for a festival of music. One of El-Dabh’s older brothers brought him along to this festival.

“He said, ‘Come on boy — let’s go,'” El-Dabh remembers. “I said, ‘Where are we going?’ He said, ‘There’s a festival.'”

And so he went — and the whole world of music was at his fingertips, with great composers such as Béla Bartók of Hungary and Paul Hindemith of Germany right there for him to see.

“I ended up meeting those guys,” he said. “I didn’t have to travel to Hungary; I didn’t have to go to Germany; I didn’t have to go to France. Here I am, 11, my big brother carrying me onto the scene. The world was there for me. I was exposed to an incredible tradition.”

From that day forth, El-Dabh took an interest in music, but composing was only something he did for fun.

He earned a degree in agriculture from Cairo University. And as he was pursuing a career in agriculture, he said he was exposed to vast cultures and traditions. Something about those traditions struck him — something that would later influence the music he composed.

The “Destiny Piece”

The way El-Dabh became a world-renowned composer was by accident. In 1949, while he was comfortably pursuing agriculture, he said a friend of his took one of his pieces he wrote for fun to a cathedral to be performed. The work was titled “It is Dark and Damp on the Front.” He calls it his “destiny piece.”

“I was unknown,” he said. “They had to fight to get my name in there. After the performance, I go out, and the (next day) the newspapers say, ‘Halim El-Dabh is an international composer’ — and I haven’t done anything.”

That piece brought him invitations first to Italy and France and then to the United States shortly after. The message of that special piece — about wartime — is one he said still resonates with him today.

“The real war is not on the front. It is inside the human being,” he said. “I still believe that. I don’t fight anybody unless I’m fighting myself.”

David Badagnani, a doctoral candidate studying ethnomusicology who is writing his dissertation on El-Dabh, said this particular piece is one of El-Dabh’s more modern pieces.

“People realized that this guy — not only is he an incredible pianist, he’s using sounds and aesthetics that are quite innovative,” Badagnani said.

The tone clusters and modern techniques link the piece to its wartime theme, Badagnani said. But at the same time, that particular piece is without the overt African and Egyptian influence of the rest of El-Dabh’s work.

Cultural Influences

El-Dabh is an ethnomusicologist, meaning he studies music and its relationship to culture. But El-Dabh’s work goes beyond just that, in that he has traveled and actually lived with people of different cultures.

“You can be an ethnomusicologist without traveling,” he said. “You can go record in the field and not be involved. My work is like a combination of an ethnomusicologist and an anthropologist because I lived in the culture.”

And when he was studying and living with these cultures, he realized there was something special about the continent of Africa.

“Africa has a lot of hidden and buried knowledge that people don’t know,” he said. “It’s not the gold, it’s not the diamond, it’s not the pearls. It’s that what we haven’t really found – because there’s something there that we are blind to. Few people, maybe like me, recognize that. And that’s what drove me to travel there.”

While there, he looked at the art, architecture, dance and songs of the country to gain insight to the people. He said he also studied residues of sound.

Residues of sound are like ancient artifacts, he said, and may be on historical temple walls and ancient work sites or on something as simple as a rock. He said he has a kind of sensitivity to sound that allows him to feel the vibrations of peoples’ voices from long ago.

“I pick that up from the people who are there today working,” El-Dabh said. “I feel that the sound is retained in their throats, in their vocal cavity, in their abdomen, and then it comes back to me.”

His favorite places in Africa to experience and study are the pristine areas that haven’t been exposed to the modern world. He said he loves seeing artistic elements of culture come together to make the society healthy.

“That’s what really was the most fantastic thing for me, to see all these things work together,” he said.

When he would enter a village for the first time, El-Dabh said he would always allow himself to be vulnerable.

“I lived in thatch-roofed houses,” he said. “I lived in whatever they lived in. I ate whatever they ate; I slept where everybody slept. If I was in Ethiopia, they called me Ethiopian.”

From ancient culture to modern instruments

Badagnani said El-Dabh combines African elements into his music in a unique way. For example, he composes for the piano in nontraditional ways by tapping the wood and plucking the strings, along with playing the normal black and white keys.

Badagnani said this is called African Pianism.

“He’s one of the pioneers to take African aesthetics and put them into Western music,” he said.

And though his work is often described as avant-garde, Badagnani said El-Dabh strikes a balance between composing music that is ahead of his time and resonating with today’s audience.

“Even though it pushes your ears a little bit,” he said, “it’s still something you can really enjoy. It’s accessible to listeners.”

In the room next to his office in the Lincoln Building, El-Dabh sits at his piano, the strings exposed, playing in a way unlike any other. He begins by playing a melody like any other pianist would, then creates drum-like and exotic sounds by hitting, plucking and strumming the piano strings. He taps the side of the piano, creating a sound resonating from the wood.

“You have a whole range of what you can do,” he says.

He’s currently working on a piece for the Korean drum and an orchestra of 18 gayageums, which are Korean string instruments. But for him, composing is never a chore. Even when he’s working at three in the morning, music is like a friend to him, he said.

And through his journeys in Africa, his years spent living in other cultures, he said one of the most important things he learned was about himself.

“You find yourself,” he said. “You learn about yourself. You learn about what you’re doing. You learn about who you are. You learn about the make-up of yourself — what it means to be a human being. I learned that we are all one. There’s no difference between me and you and everyone in the world.”

Contact minority affairs reporter Christina Stavale at [email protected].