Remember the past, continue the struggle: the legacy of the Tent City protests at Kent State

April 27, 2020

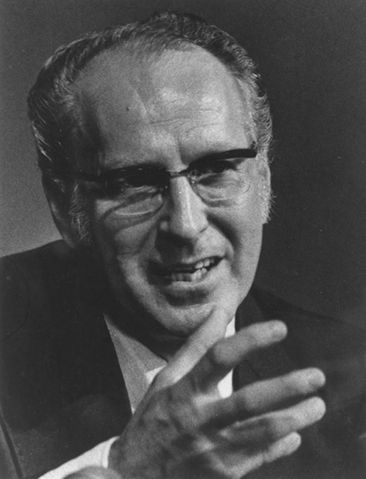

Alan Canfora hid behind an oak tree at the bottom of Blanket Hill on May 4, 1970. He had been shot through his wrist by the Ohio National Guardsmen, who opened fire on Kent State’s campus during an anti-war protest, killing four students and wounding nine. More than 60 shots were fired in 13 seconds. The tree shielded Canfora from other bullets that came his direction.

Approximately seven years later, Canfora would be one of 194 people who were arrested at Kent State for their roles in the Tent City protests. For two months, demonstrators camped in tents on Blanket Hill in opposition to the university’s decision to build a gym annex on part of the land where the May 4 shootings occurred.

Although the gym annex would eventually be built, the protests demonstrated how students, activists and May 4 survivors would shape the legacy of the tragedies and force the university to acknowledge the everlasting effect they would have on Kent State’s campus.

University distances itself

In the years that immediately followed the May 4 shootings, Kent State sought to distance itself from the tragedies that happened on its campus. Enrollment dropped 13% in the four years after May 4, according to Cleveland.com. Under Glenn Olds, president of Kent State University, the university decided in 1975 it would not commemorate the tragedies beyond the first five years. Many saw this as an attempt to erase history, Tent City participant Mike Pacifico says.

“Basically for five years, from 1970 to 1975, the university had had a commemoration every year,” he says. “And then in 1975, they said, ‘Enough is enough. We’re done memorializing. We’re done commemorating.’”

Pacifico was a high school senior and anti-war activist when the shootings occurred. He had already been accepted to Kent State.

“It was a pretty weird time for me, knowing I was going to a university who much earlier really held no significance on the international scene and now was somehow famous around the world,” Pacifico says.

Following the university’s decision, students and community members formed the May 4 Task Force, an organization designed to preserve the memory of the students who had been killed. The task force, which planned the May 4 commemorations from 1975 to 2019, emphasized the increasing role of students in the remembrance of the tragedies.

“That reinvigorated the importance of students commemorating because it showed for that crowd that the university could not be trusted,” says Mindy Farmer, director of the May 4 Visitors Center. “So I think that’s one way in which it affected commemorations. It made the push for students to lead the effort even stronger.”

The construction of the gym annex also renewed the community’s desire to keep the memory of those who had been killed on May 4 alive, Canfora says. When the university announced its decision to build the gym annex, it awakened the campus and prepared the community for action, he says.

Gym protest begins

Opposition to the construction of the gym annex developed throughout the 1970s. In 1976, several students went to a Kent State Board of Trustees meeting and expressed their concerns about the proposed site of the gym annex. However, the Board of Trustees voted to approve the building’s progress report and move forward with its plan to build on the site.

The university argued building the gym annex on part of the May 4 site would be cost-effective, because it could incorporate three existing walls into the facility, which would save money on heating lines, locker rooms and shower space, according to University Libraries. In addition, the proposed location required no new parking lots and would provide intramural and recreational programs with a centralized meeting location.

However, Farmer says this justification fails to make sense, because there were proposals to slightly turn the gym annex that would allow it to stay in the same space without encroaching on the site of the shootings.

“It’s another step in the legacy of mistrust for the people who participated in Tent City and the people who watched how the administration, especially in the immediate years following the shootings, reacted,” Farmer says.

Protesters learned the Board of Trustees was meeting in Rockwell Hall to discuss construction of the gym annex. Approximately 250 protesters marched to Rockwell Hall and occupied the second floor until the next morning. During this demonstration, they formed a new group, the May 4 Coalition, and created a list of demands to give the administration.

“We all came out of there unified as a powerful new organization called the May 4 Coalition,” Canfora says. “And we had listed eight demands. And we really started to bond, personally and politically.”

These demands included: never altering the site of the shootings, not punishing anyone for the demonstration in Rockwell Hall or missing classes on May 4, naming buildings for the four students killed, canceling normal university activities every May 4, acknowledging the shootings as an injustice, maintaining university status for the Center for Peaceful Change and reopening negotiations with the United Faculty Professional Association.

The university agreed on May 12, 1977 not to punish those who missed classes on May 4 or participated in the Rockwell demonstration, to reopen discussions with the United Faculty Professional Association and to keep full university status for the Center for Peaceful Change. It sent the demands to name buildings after the students killed and cancel university activities every May 4 to committees for further discussion and rejected those of never changing the site of the shootings and recognizing them as an injustice.

Dissatisfied with Kent State’s response, members of the May 4 Coalition gathered to discuss their next steps. They talked about creating a tent city to block the university from construction. “We had to do something about it,” Pacifico says. “So it was just simply trying to preserve the truth about May 4, 1970.”

That night, Canfora said he pitched the first tent on Blanket Hill. Over the next few days, more tents appeared. Soon more than 100 tents occupied the proposed site of the gym annex, the demonstrators determined to protect the area from construction.

Tent City

From May 12, 1977 to July 12, 1977, more than 100 protesters lived in tents on Blanket Hill. It was a diverse community in terms of both class and status, Pacifico says. Students, community members and people from across the country, including children, resided in the tents.

The sense of community quickly became an important aspect of the protests. Participants gathered for daily meetings that sometimes consisted of more than 100 people, Pacifico says. Tent City also had a health tent, daycare tent and kitchen. At the time, Blanket Hill looked more like a campground than part of a college campus. Brightly colored tents sprawled across the grass and lined the university’s walkways. Demonstrators sat on picnic blankets on the hillside. Laundry hung from clotheslines strung along the trees.

“We really did have what we call ‘Tent City,’ and we thought it was like a city,” Canfora says.

Pacifico remembers one day when demonstrators met to discuss whether they should continue to occupy Tent City. They knew they would be arrested if they stayed, he says. As they argued their positions, they decided to split into two sections. Those who wanted to be arrested moved to one side and those who did not went to another. When it became clear the majority intended to stay until they were arrested, Pacifico was overcome with emotion.

“We went back to our tents and that was a very emotional moment for me,” he says. Police arrested 194 demonstrators on July 12, 1977, including the parents of Canfora and of Sandy Scheuer, one of the students killed on May 4.

“There was such a beautiful sense of community and also a sense of political solidarity,” Canfora says. “We knew that our cause was important and justifiable, even to the point where on the day of July the 12th, when KSU got a court injunction and they had the Portage County sheriffs come there and arrest us.”

The aftermath

Construction for the gym annex began in September 1977 despite continued opposition. Canfora, who was on a lecture tour of East Coast colleges at the time, heard about it through a phone call. He was devastated to learn bulldozers knocked down dozens of trees on Blanket Hill — the same hill where he hid from bullets seven years earlier. Although the tree that shielded him still stands, it was difficult to know the others had been removed, he says.

“I saw the real sense of personal loss when those trees were knocked down. It was very sad,” Canfora says.

By the summer of 1979, employees moved into the gym annex. Kent State’s response to May 4 did not see significant improvement until the 1990s, when the university began to embrace its responsibility to educate future generations on the shootings, Canfora says. Kent State opened the May 4 Memorial during the 20th commemoration in 1990. Nine years later, the university placed markers in the spots in the Prentice Hall parking lot where the four students had been killed.

As the years progressed, Canfora says he believes the university developed a sense of understanding for the activists and their mission. “I think they did learn to respect the May 4 activists and the families and the victims and our determination to fight for truth and for justice,” he says. “I think they realized we weren’t going away […] that we were being advocates on behalf of those four students who were silenced forever in 1970.”

Pacifico also thinks the university’s reaction to May 4 has evolved over time. He says the opening of the memorial was the first time he and many of the other demonstrators felt like they achieved a major victory.

“It [Tent City] kept alive the memory of May 4, 1970. It enabled us to today have a 50th anniversary, to have a visitor’s center […] If that didn’t happen, nothing after that we take for granted would have happened,” Pacifico says.

Some feel Kent State’s efforts to commemorate May 4 improved, others see the gym annex, which houses classrooms and athletic facilities, as a physical reminder of the years of hostility. The university held a community feedback session in 2018 to discuss plans and gather ideas for the 50th commemoration of May 4. The number one suggestion it received was to tear down the gym annex, according to Farmer. “It’s a major scar for the May 4 community, and it’s a source of mistrust,” Farmer says.

Pacifico participated in the feedback session. He was at a table with other Tent City participants when the suggestion was proposed. Although it was somewhat tongue in cheek, he says they hope to see the gym annex removed.

Canfora also believes one day the facility will be torn down and the area preserved. “Hopefully the beautiful terrain, the land, the sacred area there where the May 4 tragedy occurred will be restored to its 1970 look,” he says.

Graffiti has appeared on the gym annex during many previous May 4 commemorations, Farmer says. She expects the 50th commemoration will be no different. The university has taken more accountability for the shootings, she says, but what has not changed is the cause for the building to come down.

Tent City can serve as a reminder that if students feel strongly about something, they can find others who share their values and work together to fight for justice, especially at Kent State, Pacifico says. The legacy of May 4, 1970 includes the struggles the community went through to see that the tragedies were remembered, and it will continue to transform as new students learn about the shootings and react to them in the years that come.

“You’re just not remembering history or reciting history,” Pacifico says. “You’re living and making history.”

The article above is from this semester’s special edition of The Burr that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the May 4, 1970 shootings. To read more, visit the full magazine on TheBurr.com.

Paige Bennett — [email protected]