Court reporters crucial to judicial process

February 20, 2006

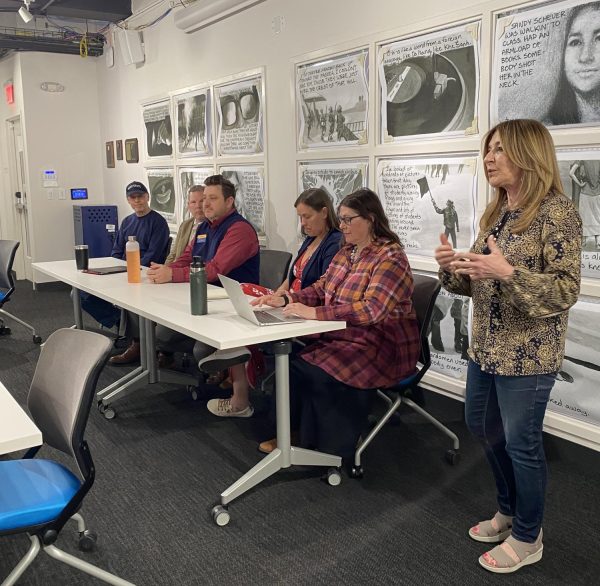

Rebecca Park has been a court reporter for 31 years. She has worked many high-profile court cases, including the James Trimble trial last fall.

Credit: Carl Schierhorn

Every single word spoken in Judge John Enlow’s common pleas courtroom is filtered through one person.

This person must type at least 225 words per minute and understand medical and legal terms without skipping a beat.

Job demands

As the official court reporter, Rebecca Park is up to the task. She has the sole responsibility of putting all court proceedings on paper.

Park, 50, has been a court reporter for 31 years and worked with Enlow for nine years. She has assisted with trials ranging from medical malpractice to murder, most notably the James Trimble trial last fall.

Park’s job is not the typical 9-to-5 kind. In addition to recording court proceedings, she also organizes evidence and provides transcripts – copies of everything said at trial – to those who ask for them. Attorneys commonly ask for a transcript to use for an appeal. To finish these transcripts, which are sometimes hundreds of pages long, Park will come to work early, skip lunch or stay late.

“It gives me a sense of satisfaction to be able to finish something like that,” Park said.

Training for the job

Becoming a court reporter is not as easy as being able to type fast, Park said.

“We have to look unbiased and detached,” Park said, “It doesn’t mean I don’t feel anything, but when I am working, I can’t show it.”

In addition to being unbiased, aspiring court reporters are required to type at least 225 words per minute and complete a program accredited by the National Court Reporters Association. It is typically two to four years long, but the actual length of the program may vary because it’s based on skill level, Park said.

Multivoice training courses are also required, which help the reporter figure out who is saying what when everyone is speaking at the same time.

“I can’t take the record if everyone’s yelling over each other,” Park said. “I’m allowed to stop people and ask them to repeat themselves, but I try to stay out of it as much as possible.”

Many court reporters also have to pay for their own equipment.

A stenography machine, the miniature typewriter reporters use, can cost about $4,000, plus the transcription software, which turns a jumble of letters into words. The software costs about $4,000 as well.

Enlow said Park’s software can save him from legal troubles.

“If we plug in her computer, you can see everything on the screen,” he said. “That’s so, on appeal, they can see if I did anything wrong.”

The benefits

Park said she enjoys her job most of the time.

“I get to see the best and worst of people with my front-row seat,” she said. “If I don’t like what I’m doing today, it will change tomorrow.”

She said the downside is that what she hears in the courtroom can be sad.

“You see some things you wish you didn’t know about,” she said. “It’s also a small town, and you see people you know.”

Although Park spends most of her time in court, that is not always the case for others.

Marshall Jorpeland, director of communications for the National Court Reporters Association, said most reporters do not work in court.

“We have about 20,000 working reporters in our membership and estimate that there are in the neighborhood of 45,000-50,000 reporters in the United States,” Jorpeland said. “But many are independent and do work outside the courtroom, as opposed to being employees.”

Enlow said he is glad Park is one of his employees.

“We have fun,” Enlow said. “You have to be able to laugh in this kind of job. And she’s very professional.”

Courtroom bailiff Bob Burns agreed.

“She really knows her stuff,” he said. “She’s the best.”

Contact public affairs reporter Erin Hopkins at [email protected].