EDITORIAL: Steroids strike out in MLB

November 21, 2005

On Tuesday, literally hours before Congress was set to vote on its own legislation about baseball and steroid use, Major League Baseball’s commissioner, Bud Selig, announced tougher penalties for steroid use and, for the first time, testing and penalties for amphetamine use, the newest form of performance-enhancing drugs.

The new penalties are a 50-game suspension for the first offense, a 100-game suspension for the second and a lifetime ban for the third. (An appeal for reinstatement can be made after two seasons of being banned.)

This editorial board supports Selig and Major League Baseball in taking the initiative to self-regulate and for leaving the federal government legislatively out of the issue.

After the Congressional hearings in March, which were largely in response to Jose Canseco’s confession of steroid use in his autobiography, Juiced, there was much discussion as to whether Congress should even interfere with MLB policy. However, enough bantering about athletes as role models and the unsaid feeling that baseball is America’s sport and should be protected even unto legislation, got a number of MLB players, past and present, testifying before Congress.

The result was a startling display of often angry rebuttal of any allegation, the most animated being Rafael Palmeiro who testified before Congress, “I have never used steroids. Period.” Palmeiro was suspended for 10 days in August, the previous first-time offender punishment, after testing positive for steroids.

Palmeiro, one of baseball’s greatest athletes with more than 3,000 hits and 500 home runs, is one of only four players to achieve such statistics with the list rounded out by Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Eddie Murray – all three Hall of Fame players. His suspension helped the MLB Player’s Association realize the problem was real enough that both Selig and Congress would continue to pursue it. As such, Donald Fehr, executive director of the player’s union, agreed to Selig’s proposal, and it will be ratified in time for the 2006 season.

Essential to baseball are the same ideas that are essential to all games of contest. There must be a skill involved that, through practice, can be increased. There must be some element of luck. Finally, there must be as fair a competition as possible. We try to make the competition as fair as possible by implementing rules that not only allow freedom to pursue new ways of improving, but that also rely upon agreement to not improve in other certain ways.

Games are only fun when the playing field is level. It wouldn’t be much of a contest to spot someone two “Xs” in a game of tic-tac-toe, just as it isn’t fair for some players to desire to destroy their bodies in an attempt to hit harder, throw faster or run quicker.

If baseball hadn’t made a stand on this issue, we could have forgot about athletes being role models, as no one would have continued to watch. If the playing field became too uneven, the excitement would have been taken out of the game.

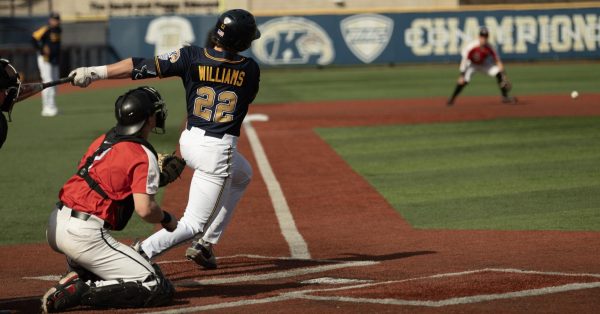

By baseball ruling as it did, it saved itself and allowed these players to continue to fill the minds of boys and girls around the world with dreams of cracking bats and roaring crowds.

The above editorial is the consensus of the Daily Kent Stater editorial board.