Jobs not necessarily made in America

October 19, 2005

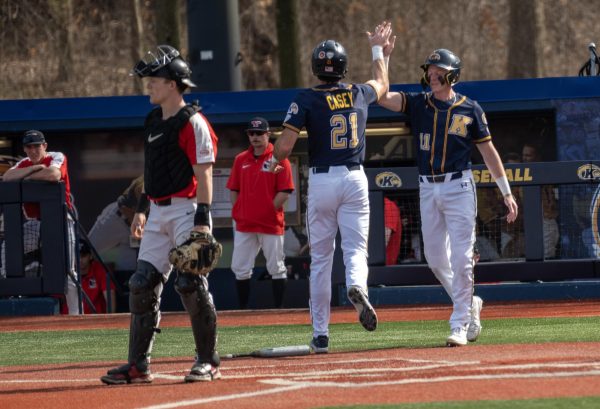

Ziyoda Abdushaidova, graduate assistant in the Gerald H. Center for International and Intercultural Education, sorts handouts to be given to students for their upcoming trips to Italy and Ireland on Tuesday. Abdushaidova has been working at the center in

Credit: Steve Schirra

If it hadn’t been for a friend from the Peace Corps and his mother, Ziyoda Abdushaidova said she might never have come to Kent State. The cultural foundations graduate student found her job when her friend’s mother heard about a graduate assistantship opening at the Gerald H. Read Center for International and Intercultural Education.

“Since I’m an international office, I figured I should give it to an international student to support the work we do here,” Academic Program Director Linda Robertson said.

But the wait wasn’t over. Abdushaidova still had to obtain the I-20 form and visa that would permit her to work in the United States. She didn’t even tell her former employer she was leaving Uzbekistan until a month before her departure.

“I wanted to make sure I had my I-20 and my visa,” Abdushaidova said. “It was very scary getting my visa because you always fear not getting one. It’s very hard to get an American visa. People gossip and say this person was crying after their (visa) interview; there were 50 interviews today, and only 10 got visas.”

Job searches are seldom easy for any student. For an international student, the process can be especially difficult and confusing.

“I think they struggle a bit with the multi-step process,” said Julie Stieber, associate director of the Career Services Center. “It involves a lot of steps and going to a lot of different places to get done what a domestic student could do with one visit here – and it has to be done in order.”

To help international students through the job process, the Career Services Center offers a list of guidelines that show the steps in order.

“We do what we can to help them understand what they need to do and the order in which they need to do it,” Stieber said. “We also have some resources in our Career Services Library directed to international students about finding your way through the U.S. job process.”

Depending on planning and how quickly each of the forms is completed, the whole process can take international students anywhere from two days to two weeks, Stieber said.

It took two weeks when technology graduate student Gonul Arslan came to the United States from Turkey last year.

“It was challenging; everything was new to me,” Arslan said. “Last year when I came here there were three or four Turkish people here who helped me. We went to the Social Security office together, and they explained the procedure.”

The language barrier

The paperwork challenges are not the only ones faced by international students seeking a job. Language also is an obstacle.

“Although you learn the language in your country, when you come to the country that speaks the language, it’s very different,” Abdushaidova said. “You feel like you don’t know anything.”

After working as an interpreter and teaching study abroad students from America, Abdushaidova’s English is nearly flawless, but she said she still has difficulties.

“I might understand on the surface but not the bottom – or even that there is a bottom,” Abdushaidova said. “When I write a letter, I have to ask how to say something or ask, ‘Is this OK?'”

One of the challenges Abdushaidova faces is determining how to address professors and what level of familiarity is appropriate.

“I got into trouble a little with one professor who I called Mr. instead of Dr.,” Abdushaidova said. “He e-mailed me back. Later, Linda told me I should always call them Dr. to be safe, and if they aren’t and want to be called something else, then they can tell me.”

Employment difficulties

According to jobweb.com, some employers are reluctant to hire international students because they are concerned about the student’s ability to communicate, don’t want the hassle of extra paperwork or feel international students take jobs away from Americans.

“It is more competitive,” Abdushaidova said. “For example, with the graduate assistantship I see it’s more competitive because I’ve come from a very different background. I’ve not worked with college students. I felt no one was going to hire me because all I’ve done is office jobs, and that’s kind of easy.”

Arslan, who has worked at the Kent Market II, Rosie’s Diner and Einstein Bros. Bagels, said she has had mixed experiences with her employers.

“If you are an international student, some employers will behave differently toward you,” Arslan said.

In her experience, some of her employers gave international students the hardest jobs and showed little concern for them.

“I’m strong enough to handle that stuff,” Arslan said. “They have to know this isn’t my language. It’s hard because it’s not my culture. I had to work there because I had to earn money.”

Job constraints

Money is often a difficulty for international students, said Debra Lyons, immigration assistant for International Student and Scholar Services. By federal law, international students cannot work off campus unless they have been in the United States for one year and are working as part of their practical career training. According to the 2004-2005 Kent State Fact Book, 222 of the 915 international students enrolled at Kent State last year worked on campus.

International students also may not always arrive early enough to get the best on-campus jobs, Robertson said.

That was the case for Arslan, who originally hoped to get a graduate assistantship but worked in Kent Market II her first year.

“By the time I came here it was a little late to find a job somewhere else,” Arslan said. “I applied for a job in the library but nothing happened, and one week later I started in the cafeteria.”

Another difficulty international students face is that the federal government limits the number of hours they are allowed to work.

“International students are limited to 20 hours a week, whereas domestic students can work 30 hours a week,” Lyons said.

During the school year, international students are eligible for gradudate assistantships, which give students free tuition and a stipend. But during the summer these assistantships don’t apply.

“When I came, I didn’t ask my parents for money because they can’t afford that all the time,” Arslan said. “So that was hard to get your budget for one month. I was kind of starving, I can say. I had to pay my rent, my insurance and my groceries, and I had a little money I couldn’t spend after this.”

Abdushaidova said she hopes to stay in the United States and work after graduation but wonders how it will work out.

“Because I’m not a citizen in the States I feel I don’t have enough experience to work in this field,” Abdushaidova said. “I will seek companies nearby to get an internship to gain experience. It’s still scary. Each time you go, you fear, ‘Am I going to get this job?'”

Contact alumni affairs reporter Joanna Adolph at [email protected].