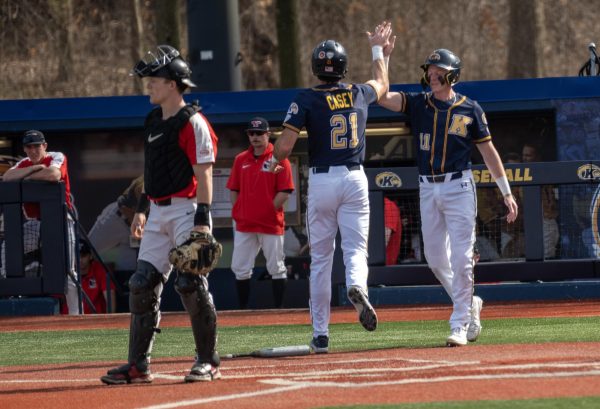

First-generation students face challenges

September 8, 2005

Raven Montanez, freshman nursing major, is the first of her family to go to college. First-generation students, like Montanez, face challenges, such as relating their college experiences to their families.

Credit: Steve Schirra

Raven Montanez’s mother always encouraged her to go to college.

Her mom never attended and always tells Montanez how hard it is without a degree.

As the oldest of five children, Montanez said her mother has a lot of expectations for her to be successful. Montanez has cousins who have gone to college, but she is the only person in her immediate family to go.

“I have to explain everything, detail for detail, to my mother about the college process because she never went through it. Everything that’s new to me is new to her,” said Montanez, a nursing major and first-generation student.

A first generation student is one whose parents or guardians did not receive a bachelor’s degree, said Gary Padak, dean of Undergraduate Studies.

Some people think the number of first-generation students should have dramatically decreased since the academic revolution of the 1960s and 70s, but Padak said the federal government strictly defines them. Even if parents had attended some college or received an associate’s degree, a student is still considered first generation.

Providing a jump start

The university takes more time and effort with first-generation students, Padak said. Financial and social issues, such as lack of support at home, can cause problems.

Parents who did not complete college may not be able to earn the higher income of their peers with degrees, making it harder for their children to go to college.

“You may be able to get into college, but you may not be able to attend,” he said.

Kent State offers programs to first-generation students to help them overcome such challenges. The Upward Bound program prepares high school students for college, said Geraldine Hayes Nelson, associate dean of undergraduate studies.

Many first-generation students do not realize college is an option, and the program helps prepare them for the possibility, with prep classes and scholarship searches.

Upward Bound is a TRIO program funded by the U.S. Department of Education, according to the undergraduate studies Web site. First-generation students and students with financial needs can be assisted by TRIO.

Another TRIO grant sponsors tutoring at the Academic Success Center. Aside from first-generation students, the grant can be used to help students with low incomes or those with disabilities, said Christopher Tokpah, student success specialist.

The grant funds services for about 300 students, Tokpah said, and the university provides additional money for all-access tutoring. Students sign up at the beginning of each semester. If there are more than 300 students, the Academic Success Center will try to accommodate them by giving them other options, such as open tutoring provided by the university.

From information students provide at PASS, the department can seek out students who may be in need of its services. Tokpah said the center will begin sending out information to the three target groups of students before classes start, so they can know what programs are available to them.

“We’re trying to be a little more pro-active,” he said.

Dissolving the gap

Montanez said she had never heard of the programs, but she also said she does not feel she needs them. Academically, she said she has support from her teachers and her mother backs her decision to attend school.

Not all first-generation students have this kind of support, Padak said. Some parents dismiss college as an option, telling their children that it is an unnecessary step in the working world. Most fall between these two extremes, he said.

The main problem is that no one at home has the experience to guide them through common college problems, Tokpah said.

“They’re trying to blend into an environment where they have no support from home,” he said.

This gap can dissolve when students have siblings who attended college, Padak said. They are still considered first generation, but have someone to show them the ropes.

Peer groups pose another social challenge, Padak said. If a student is from a lower-income area and classmates are not attending college, it is likely that the student will also not attend.

However, the opposite also applies. If everyone in a student’s peer group is attending school, the student may find a way so he or she can also attend.

Across the nation, the amount of people without a bachelor’s degrees still outnumber those with a degree almost 3-to-1. According to the 2000 Census, about 24 percent of the population ages 25 and older had at least a bachelor’s degree, and about 21 percent of people in Ohio had attained such a degree.

The amount of first-generation students, while falling, is still high, Padak said.

In 2003, 42 percent of students at public universities were the first generation for their fathers’ side of the family and about 45 percent were for their mothers’ side, according to the Cooperative Institutional Research Program, an annual study of incoming college freshmen across the nation.

The statistics were higher at Kent State, with 57.5 percent as first generation for their fathers’ side and 59.9 percent for their mothers’ side in 2003. That was the most recent year Kent State had participated in the survey, Padak said.

While Padak said he does not know why Kent State’s statistics are higher than average, students like Montanez are helping to drop the numbers.

Contact administration reporter Rachel Abbey at [email protected].