State support dwindles, students pay

May 4, 2005

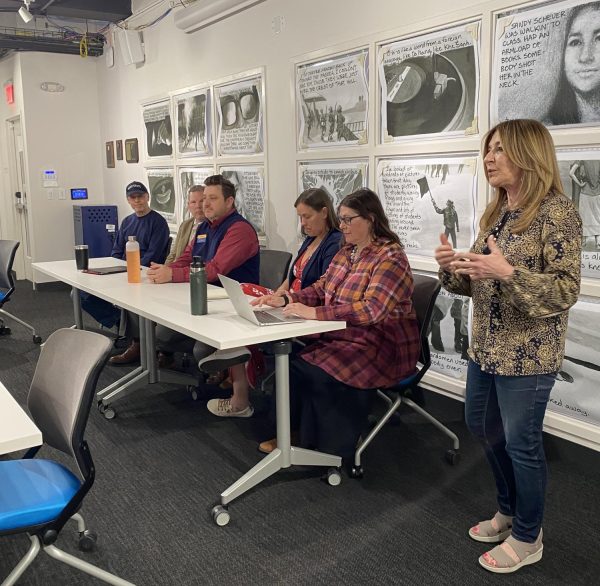

When Vice President for Administration David Creamer proposed a 6-percent tuition increase Monday, he cited less state support for higher education as the major cause.

Money from the state, he said, has remained flat this year, and an increase in tuition was necessary to cover “what state support hasn’t provided.”

Ohio has gone through a depression with its funds, said Pat Myers, director of Government Relations. Declining state revenue has coupled with an increase in costs for K-12 education, prisons and Medicaid.

“Which leaves very few discretionary dollars for other state agencies,” Myers said. “It’s a matter of balancing the state budget. We can’t overspend like the federal government. We have to have a balanced budget.”

Creamer cited a faltering manufacturing economy with few available jobs as a major reason he does not expect Ohio’s economy to improve soon.

“Most of the budget is being tied to entitlement programs, namely Medicaid,” he said, which has created a “structural problem” with the way the state government is handled.

“Those entitlement programs are eating up a greater and greater amount of the budget,” Creamer said, “which leaves little left for higher education, unless there’s a willingness to increase taxes. It’s not that there isn’t an understanding of the importance of higher education or an appreciation of the problem that tuition increases have for families. It’s just that there isn’t the money without raising taxes.”

President Carol Cartwright said although states are pressed for revenue because of Medicaid and prison funding, finding money for higher education is about convincing lawmakers it is a top priority.

“I think there are some people who consider universities to be unwilling to be accountable,” Cartwright said. “It’s harder to make the case of the importance of higher education because it plays out over time.”

Higher education has not been made a priority by lawmakers in Ohio, State Rep. Kathleen Chandler (D-Kent) said, and consequently “students are getting such an unfair burden.”

Effects of less funding

Currently students pay for 65 percent of the cost for their education, a far cry from decades ago, Creamer said.

“That’s a change from 30 years ago when it was 30 percent, and a change from seven years ago when it was a little over 50 percent,” Creamer said.

For fiscal year 2001, Ohio provided $5,695 per student in state operating support, while in 2004 only $4,736 was provided.

Next year, students will pay closer to 2/3 of their education, Creamer said, and less state support means higher tuition for students.

In a draft document that will be presented to the Board of Trustees May 26, tuition per semester for a full-time Kent campus undergraduate will increase to a proposed amount of $3,977 — $225 higher than the current $3,752 rate.

The state’s budget has a large effect on the university’s budget, as state appropriations provided more than $110 million of the university’s total $377 million available in fiscal year 2004.

But when less of that state money is provided, the university must balance its budget.

“The university has cut significantly in order to balance its budget,” Cartwright said. “We’re at a point where there will be significant effects no matter what we do. Something has to give. In some cases its convenience, but we’re worried about crossing that line where we see quality slipping.”

Kent State has a much smaller custodial staff than in the past, Creamer said, who are maintaining 20 percent more space. The groundskeeping staff has also been reduced because of budget cuts.

“That staff is only about 2/3 or less of what it was back in 1990,” Creamer said. “We are offering many of our services with fewer people performing them. We’ve been having to adjust to this for some time, and that’s why each round of this is more difficult, more challenging.”

Creamer said a tighter budget means hiring faculty at the assistant professor level, as hiring senior faculty is more expensive. Recently, about $2 million was saved in staff layoffs.

What happens next

“It’s tight economic times,” said State Rep. Matt Dolan (R-Geauga County). “Do we throw a lot of money at higher education? No, we don’t. But there’s not a lot of money to throw around.”

Dolan said that while he understands frustration over less money being provided, what’s important is controlling state spending and spurring Ohio’s economy, which “was the focus of this budget.” After the economy is improved, so will funding for areas like higher education.

Cartwright disagrees, saying the state should not wait to improve higher education.

“We’re falling further behind every year,” Cartwright said. “And I think we’re to the point that affordability issues are of such great concern that some students are choosing not to go to college, and that’s counterproductive to the state of Ohio. We need to step up to this.”

Universities have had to find dynamic ways to replace revenue, Cartwright said

“I think most university presidents and boards I’ve talked to have done that,” Dolan said.

Finding new revenue includes new investment policies and regional development initiatives.

“What we have to remember is that those opportunities may be more volatile than state support,” Creamer said. “We rely so much less on state support. We have to find ways to replace those dollars.”

Contact administration reporter Ryan Loew at [email protected].