What are they going to call us next?

February 6, 2022

The English language enveloped words from other cultures just as European nations enveloped “discovered” countries into their empires. As a result, English-speakers are left with phrases that are a mish-mashed, melting pot of influences. But some words carry their meaning along as they evolve.

Slurs, hate speech, pejoratives, ethnophaulisms – all are synonyms for expressing racially-motivated hatred. In the United States, the history of derogatory language mirrors the country’s own history.

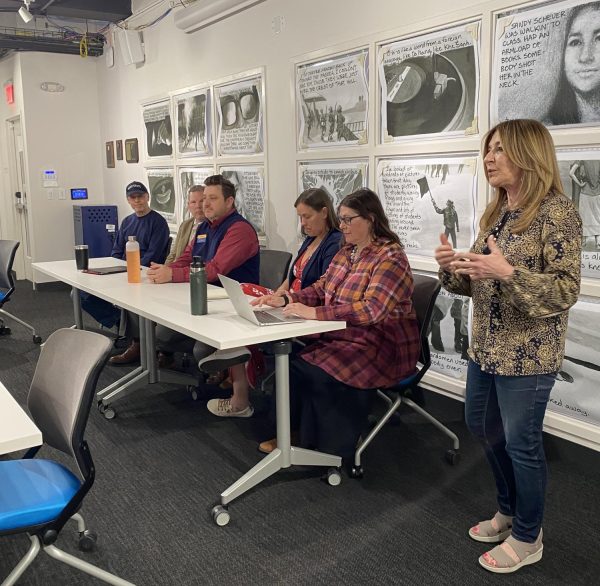

“One could say that derogatory language began with Europeans in their exploration of the planet … and the idea that they as Europeans were superior to the ‘savages’ that they discovered,” said Mwatabu Okantah, associate professor in the Africana Studies department at Kent State University. “As a result of that, Europeans developed an attitude toward the people that they claim to have discovered.”

In 1619, Portuguese slavers stole 350 Africans from their homes, forcing them to march to a port where they would board the San Juan Bautista. The ship was attacked by the White Lion and the Treasurer, pirates who stole 60 of the surviving 150 Africans.

The White Lion landed in Point Comfort, Virginia, on August 20, 1619. Settlers traded food for 20 of the captured Africans, marking the historical beginning of centuries of slavery in America.

These African people were called by the Portuguese and Spanish word for the color black, a word which would end up twisted and mispronounced on Southern lips. Latin and French adjectives contributed to the etymology, with the phonetic spelling of Americans unable to pronounce French words resulting in the N-word we know today.

Okantah, who likes to call himself “a poet disguised as a college professor,” said his experience has been “typical of what so many Black people experience.”

“I’ve been called names,” he said. “I’ve been in situations where I’ve been marginalized, been made to feel unwelcome.”

Growing up in suburban New Jersey, Okantah went to a predominantly Black elementary school. He became a minority in a white community when he started junior high in the 1960s. Although he had positive relationships with white classmates, “the specter of race was always present.”

“I went to school with kids whose parents owned businesses that were burned out during the Newark riots,” he said.

These deadly riots broke out in Newark in 1967, a reaction to police beating a Black cab driver. Over 700 people were injured, and 26 people were killed – many of them Black.

Okantah said this made school “intense, and stressful.”

An athlete in his youth, Okantah eventually came to Kent State University to run track. Classmates often treated him differently as an athlete, suggesting that he was “somehow different from other Black kids in the school.”

He continued to speak of history he lived through, moments that continue to impact him: the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.; the Black Power salute Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised at the Mexico City Olympics; the announcement of Muhammad Ali’s new name.

Muhammad Ali refusing to use his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, particularly resonated with Okantah, who would later change his own name to an African one.

“It was part of the enslaving process. African people were renamed, and we were given the names of our slave masters,” Okantah said. “As a college student, it allowed me to see how important names are. If African names were not important, we would still have them.”

Okantah changed his name forty years ago, which he described as a liberating experience. For him, the conversation regarding slurs is really about diversity.

“The planet has always been racially diverse, there’s nothing new about that,” he said. “White people are being forced to recognize that they can no longer dominate the planet and … that the people that they’ve conquered and have defined are pushing back.”

All of the labels, slurs and names that white people created for the Black community are words that he says African people never called themselves. Okantah spoke of the “devastating” effect these words have on Black people psychologically, spiritually and physically.

“Large numbers of us have bought into the impressions that were imposed upon us,” he said. “Which is to say, we view ourselves the way white society sees us.”

David Pilgrim, professor of sociology, and Phillip Middleton, professor of languages and literature, at Ferris State University wrote a piece for The Jim Crow museum explaining how the history of the N-word is tied to racial caricatures.

Pilgrim and Middleton list examples of how these slurs and ethnophaulisms were used: in book titles, as a common pet name, in music and even in the names of towns and locations. Four geoscientists, who are also women of color, wrote an opinion piece explaining that they still see racist place names today.

Representative Debra Haaland introduced bill H.R. 8455 in 2020, which “would create a committee and a formal governmental process to identify and change racist place names.”

“The historical relationship between European Americans and African Americans was shaped by a racial hierarchy which spanned three centuries. Anti-black attitudes, values, and behavior were normative,” said Pilgrim and Middleton, giving background to the continued use of slurs.

Okantah recounted when he first started studying the history of Africans in the United States, spinning around in his desk chair to grab a book with his name printed at the bottom. He quoted lines of his poetry, “I was in college when I met my first African from Africa African. I remember being confused. If he was from Africa, what did that make me?”

Okantah traveled to the South, where his maternal family lived in South Carolina. He went to plantations in South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana and Tennessee, absorbing information along the way. In 1998 he made his first trip to Africa, where he traveled to Nigeria.

He spoke of one moment he remembers as a paradigm shift: when he first heard James Brown’s song “I’m Black and I’m Proud” at a party. The lyrics made him listen.

“Up until that moment, we weren’t proud of being Black. If anything we were derisive about it,” he said. “So again, my experience with this African has made me question the labels that society has imposed on Black people.”

Okantah raised a question to encourage Black people to rethink those labels:

“What are they going to call us next, instead of asking us, ‘Who are you?’”

Sophie Young is a reporter. Contact her at [email protected].