A ‘low-key’ revolution: 50 years of Title IX at Kent State

Part one of three: Judy Devine, a pioneer in women’s sports at Kent State, played and coached during the beginnings and through the growth of collegiate women’s athletics.

Kent State’s 1975 field hockey team poses with Coach Judy Devine, center back, in front of a homemade goal cage. Each athlete is wearing her own practice gear and holding hockey sticks that were borrowed from the physical education inventory.

When Judy Devine came to Kent State in 1969, women’s athletics barely existed.

There were no scholarships or varsity letters for women athletes. There were no paid coaching positions. There was no Mid-American Conference play for women’s sports.

For decades, there were only intramurals — and cheerleading, which was managed under the male-sport-only athletic department.

“We didn’t have any experience with having uniforms or having schedules or having awards,” said Devine, who was one of the university’s first women’s varsity coaches and went on to be Kent State’s top woman administrator until her retirement in 2000. “None of that was even a possibility in our minds, because it hadn’t been a possibility at all. The girls wanted to have team rules, and they would have loved to have uniforms and come in and practice for a preseason. It was all the things the boys had been doing for 80 years.”

Then came Title IX, the groundbreaking 37-word law banning sex-discrimination in publicly funded education, which passed in 1972. After years of fighting to compete beyond intramurals, Kent State women athletes started to get some of the opportunities the men already had.

But the changes were gradual.

A ‘LOW-KEY’ REVOLUTION

Title IX was never solely aimed at sports.

The legislation followed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial and other forms of discrimination. Feminists lobbied, and in 1967, sex discrimination was added as an amendment. But women were still not treated the same as men.

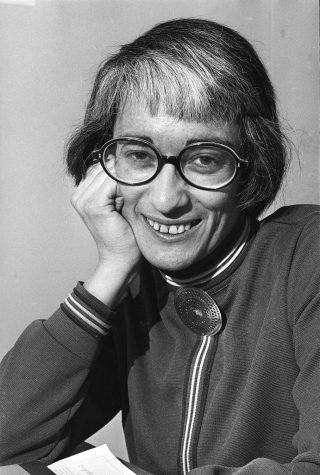

In 1969, Bernice Sandler, a part-time teacher at the University of Maryland, was struggling to get tenure. After filing complaints against the university and other schools about sex-based discrimination, she began working with U.S. representatives Edith Green of Oregon and Patsy Mink of Hawaii to give more legal protection to women in education and the workplace.

After hearings about equality in the workplace led by Green’s Subcommittee on Higher Education, Mink and Green drafted Title IX. Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana introduced the legislation in the Senate.

President Richard Nixon signed the Education Amendments, which included Title IX, in 1972.

Devine said she thought the law was deliberately low-key.

“That was partially by design of the legislators who were trying to get it through Congress,” Devine said. “[Green] realized the impact it was going to have on women faculty in colleges and universities, and she knew if she could get it through as an amendment without any hoopla that the male members of Congress would not realize the impact the legislation was going to have.”

BRING YOUR OWN: COACHES, UNIFORMS AND TRANSPORTATION

In 1969, Devine came to Kent State as a graduate student and began volunteer coaching for three women’s club teams. At the time, women’s sports were a part of the intramurals program under the Department of Women’s Physical Education.

“They had real informal organization and faculty who served as advisers for their student-run programs,” Devine said. “My first thought was, ‘Well, gosh, it would seem to me that if they had just a little bit of organization and a little bit of coaching, what might they become?’”

In her first year at Kent, Devine saw that Kent State’s female athlete experience was similar to her time as an athlete at Colorado State University.

Players had to find and purchase their own uniforms, go without a preseason and even drag their own bleachers to the fields so spectators could watch them play. Coaches drove their teams to games. Practices were scheduled when men’s sports weren’t using their facilities.

Coaches all had other university jobs or were volunteers. None were paid for supervising their teams.

“We had fairly loosely organized sports but great coaches,” said Debbie Moore, who played field hockey for Devine from 1971 to 1973 and later was associate commissioner at the Ohio High School Athletic Association for 32 years. “We didn’t have much money for uniforms or good equipment. We had to pile into cars to travel to compete. At one point, our coaches basically said, ‘You know what, we’re not doing private cars.’ There was some real trouble brewing because the people that were coaching us and administratively responsible for our programs recognized that this was wrong.”

To get any kind of funding, Devine and the other volunteer coaches needed to go through the student government, since the teams were student organizations. In 1970, they were given $12,000 to divide among 15 sports.

A year later, the first organization to solely govern women’s college sports nationally was created: the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, which organized schedules and championships.

Schools were not divided into divisions, so colleges played each other regardless of size or funding. Only a few AIAW tournament matches were televised, and no scholarships or outside recruiting was allowed.

“We thought you should invite students to come to your campus and choose your campus for academic reasons, award them academic scholarships and then say, ‘Would you like to play on our sports team?’” Devine said. “We thought that was more sound educationally than choosing a school because you wanted to play on its basketball team.”

Isabella Schreck is sports editor. Contact her at [email protected].

Part two: From intramurals to 11 varsity teams, women’s athletics struggle, grow and evolve.

Part three: The path to equality for women in Kent State’s athletic department is not always smooth. A new director is charting a new path.

Izzy is a junior journalism major who loves reading, writing, talking — and most importantly, asking a lot of questions. She previously was Sports Editor...