CNN– Fall has only just begun, but it’s not too soon to look ahead to winter, especially since this one may look drastically different than recent years because of El Niño.

This winter will be the first in a few years to feel the effects of the phenomenon, which has a sizable impact on the weather during the coldest months of the year.

El Niño is one of three phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which tracks water temperature changes in the equatorial Pacific Ocean that can have rippling effects on weather patterns around the globe. The El Niño phase occurs when these ocean temperatures are warmer than normal for an extended period.

This year’s El Niño began in June, is expected to be strong this winter and last at least into early next spring, according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

El Niño’s cooler counterpart, La Niña, played a huge role in the past three winters across the US, keeping the South dry while parts of the West received a lot of much-needed snow.

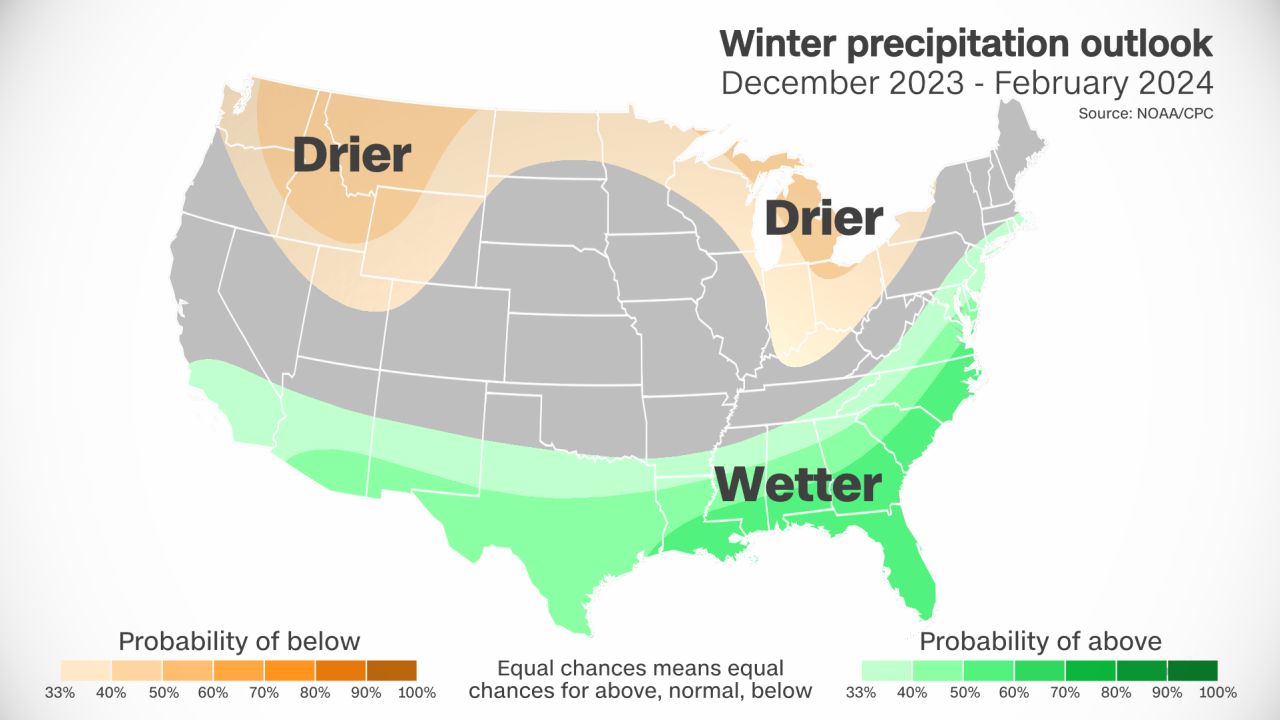

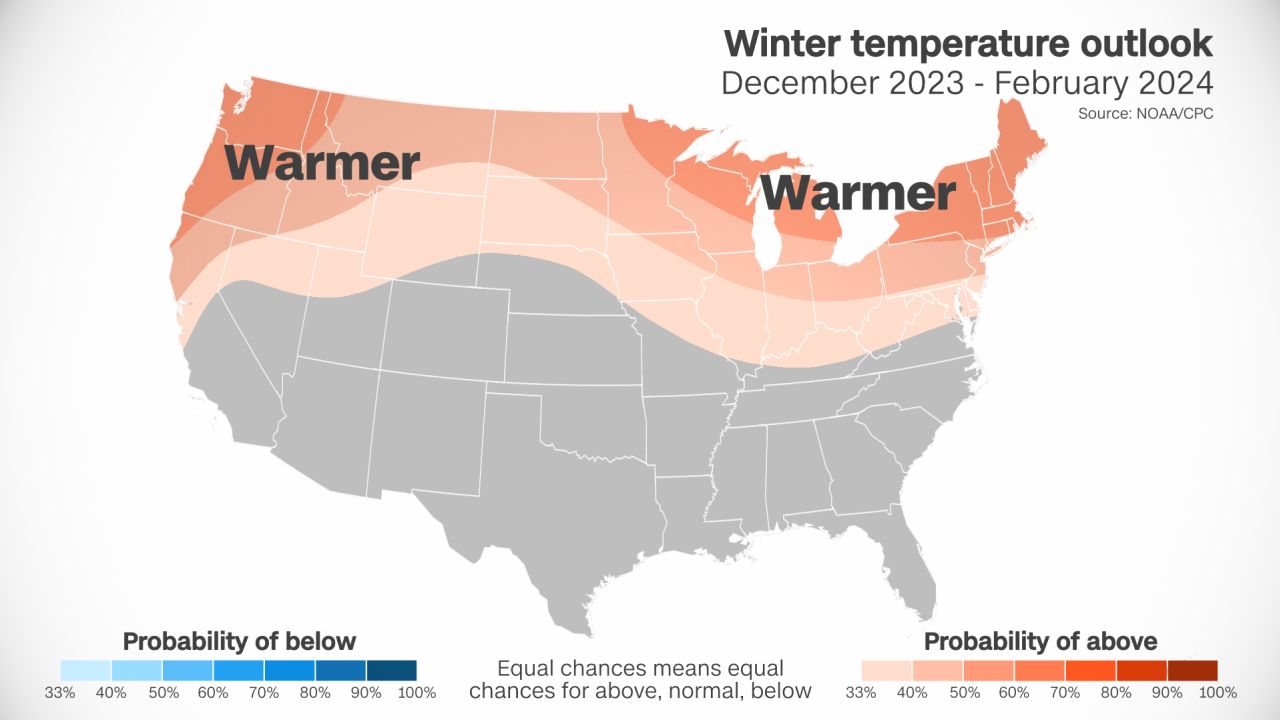

Early winter predictions from the Climate Prediction Center have many of the hallmarks of typical El Niño winters, auguring changes to come.

What could this winter look like?

No two El Niño winters are the same, but many have temperature and precipitation trends in common.

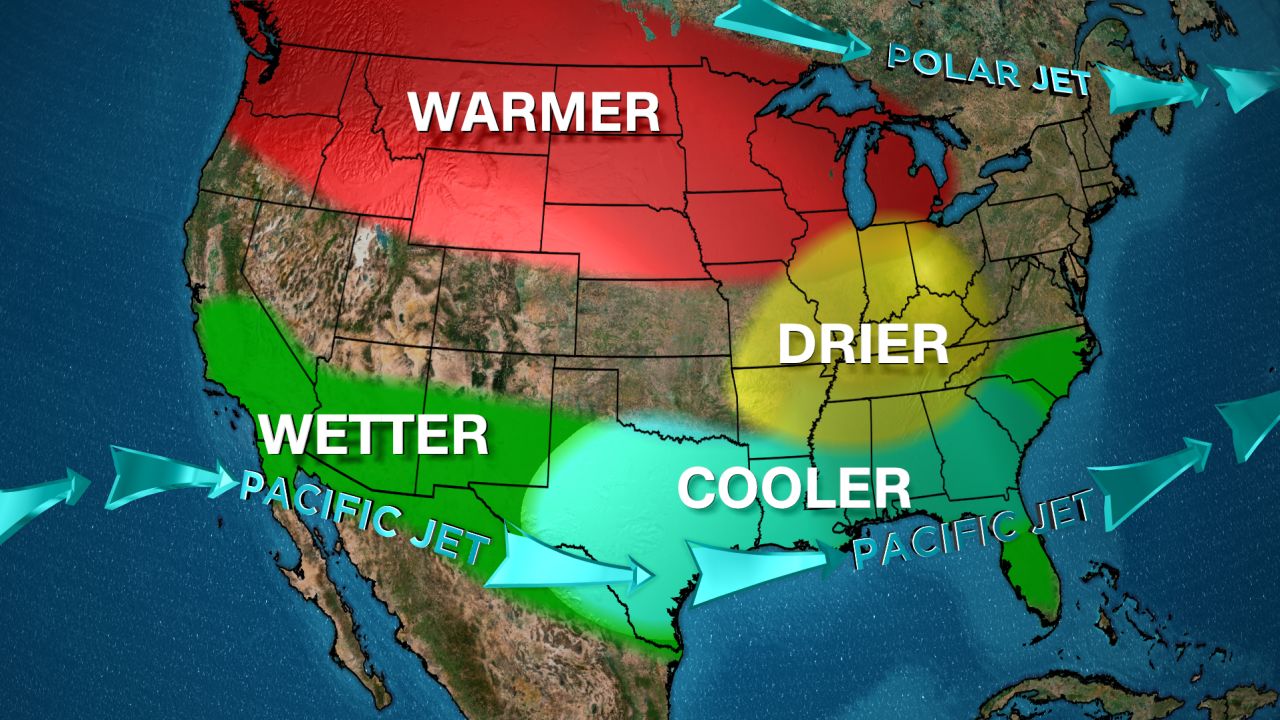

One of the major reasons is the position of the jet stream, which often shifts south during an El Niño winter. This shift typically brings wetter and cooler weather to the South while the North becomes drier and warmer, according to NOAA.

Because the jet stream is essentially a river of air that storms flow through, they can move across the South with increased frequency during an El Niño winter. More storms means more precipitation, typically from the southern Plains to the Southeast. This could be crucial for states like Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi plagued by drought.

The combination of cooler weather and more frequent precipitation may also increase the chances for wintry precipitation like freezing rain, sleet and snow to fall in the South.

El Niño typically leads to a milder winter in the North, from the Pacific Northwest to the Rockies, Plains and Midwest. Individual storms can still form and deliver bouts of brutal cold or heavy snow to these regions, but they are typically less frequent.

This would be bad news for portions of the Midwest also dealing with extreme and exceptional levels of drought, and for snowpack in the Pacific Northwest – a key water source for the region.

El Niño winter patterns are less regular in California, the Southwest and the Northeast.

The frequency of storms and uptick in precipitation across California and portions of the Southwest may depend on the overall strength of the El Niño. A stronger El Niño may lead to more storms, low elevation rain and high elevation snow, while a weaker version could hang the Southwest out to dry.

The Northeast doesn’t have a well-defined set of expectations during an El Niño winter. The region can be milder overall like its other northern counterparts, but it can also be at the mercy of robust coastal storms moving along the Atlantic Coast.

Looking back at recent El Niño winters can also help visualize what the upcoming winter may have in store:

- A weak El Niño during the 2018-2019 season had several notable storms, including one in December that brought snow and ice from Texas to the Carolinas. The season was also the wettest winter on record for the US mainland and featured above-average temperatures across much of the East, according to NOAA.

- A very strong El Niño during the 2015-2016 winter contributed to the warmest winter on record for the US mainland, according to NOAA. The warm winter didn’t prevent massive snowstorms, including a deadly blizzard that brought East Coast travel to a standstill.

- The 2009-2010 winter was the last with an El Niño of the same forecast strength as this year. It was quite cold across the southern and central US and very wet and snowy along the East Coast, according to data from NOAA. The season was notorious for multiple blizzards slamming the Northeast in rapid succession.