Faculty and students have studied wetlands on campus for years so they can understand the history to better preserve and protect the environment for the future.

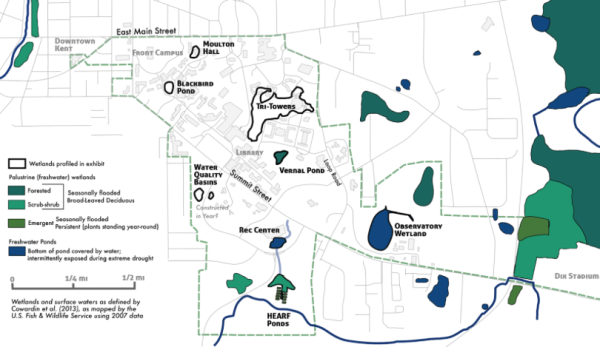

Originally, the wetlands were low-lying areas that would flood for all or part of the year and a fair amount of the land around campus consisted of farm fields and forestry. Although, when the campus was in need of expansion with its further growth over the years, most of the wetlands were drained and built over top of, leaving a significantly smaller number of wetlands and a change in the environment around them, as explained by associate professor of the Department of Geography, Jennifer Mapes.

While looking at the history of the diminishing number of wetlands over the years, Mapes explained the main reason why.

“They mainly focused on ‘what do they need’ on Kent campus,” Mapes said. “In each case, it is really just about the expansion of the university, the need for parking, the need for construction and you can’t do any of those things if you have the wetland.”

Mapes, one of her masters students and graduate assistant of the Department of Geography, Seth Rainey, and associate professor of Biological Sciences, Lauren Kinsman-Costello, looked into the archival research at Kent State and delved into the masterplans, photographs, old books and documents that were preserved.

“Efforts to restore wetland generally began around the time of the environmental movement in the [70s],” Kinsman-Costello said. “On-campus wetland construction, restoration and management at Kent State has recently been driven by a need to manage stormwater flows and mitigate flooding.”

The “Observatory Wetland” behind the University Facilities Management experienced some restoration in the 1990s and prairie restoration in the early 2000s, Kinsman-Costello explained.

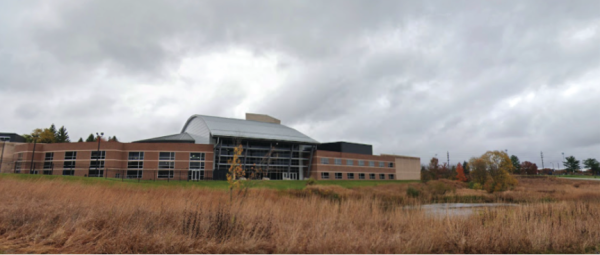

The wetland behind the Student Recreation and Wellness Center was also built in the early 2000s. A different wetland had inhabited the land prior to construction, although it got drained in the process, Rainey explained. So, the campus created another wetland downstream.

Other places that used to be considered wetlands before they were drained were Blackbird Pond and the land located where Tri-Towers was built, as explained by Mapes. Although, they too were drained and filled for further construction and expansion of Kent State main campus.

The main campus is not the only location trying to preserve the wetlands in their area. Stark campus has put forth involvement in taking care of the environment around them, regarding their Pond and Wetland Research Area.

The research area is used as an educational resource space as described by associate professor of Biological Sciences at Stark Campus, Robert Hamilton. A variety of groups use this space for classes like biological science, arts and creative writing classes, to name a few.

“Students are really getting a lot of use out of this space,” Hamilton said. “From a chemistry point of view, there is a lot of water chemistry analysis that goes on. From a geology point of view, there is a lot of water level monitoring. From a biological point of view, there is a lot of vegetation and aquatic surveys and both by the students and the general public, there is a lot of bird watching.”

At Kent State’s main campus, the Center for Ecology and Natural Resource Sustainability has also put forth more effort for education with its students involving the surveying of the environmental sites that Kent State owns, Rainey said. Students have been able to survey the plants and animals in the various ecosystems on and around the campus and take into account more sustainable methods to keep the environment clean.

“We’re very fortunate at Kent State to have such a diversity of aquatic ecosystems literally in our backyards,” Kinsman-Costello said. “It’s a fantastic resource for research and education, and we have a meaningful opportunity as a campus community to be responsible stewards of our environment.”

At Kent Stark, numerous animals and wildlife has been reintroduced or just reinhabited on its own to the wetlands and land around the Pond and Wetland Research Area.

Originally, the pond was stocked with a variety of fish like bluegill, smallmouth bass and catfish. A lot of this area of northeast Ohio used to be considered prairie land used agriculturally but mostly abandoned and turned into forest. So, the Stark campus cut down some vegetation and turned some of the areas back into prairie, causing prairie plants like Little Bluestem to reappear, Hamilton said.

Little Bluestem is not the only thing to inhabit the research area. The Canton Audubon Society (CAS) counted and found a variety of 37 bird species that inhabit this area, Hamilton said. Other animals that had been spotted were red foxes, geese, deer, ducks, red-tailed hawks and some other exotic wildlife.

This could leave you to wonder, why wetlands are so good for the environment, since many ecosystems inhabit it, Rainey said.

“Wetlands are one of those land types that some people may think of as disgusting, but they actually provide a lot of good ecological functions,” Rainey said. “They help filter groundwater, so rainfall can go through different levels of the wetland, which can provide better water quality. It also helps promote biodiversity with plants and animals.”

Involving better water quality, Kinsman-Costello supervised a couple of different student projects monitoring the campus center drive water quality basins. The students found preliminary results that suggested these water quality basins are effective at minimizing road salt concentrations, at least in surface waters, which could lead to constructed wetlands to improve water quality for campus.

Even with its successes, there are sometimes struggles with preserving the wetlands on the main campus or restoring them on Stark campus, Hamilton said.

“Ponds fill in over time,” he said. “So, if you want to keep the pond for a longer period of time, the pond needs to be dredged, but that is both expensive and needs to be disposed of in a proper manner.”

Hamilton also explained there are high expenses overall, which limits Kent Stark’s budget to maintain this environment. With help from Dominion Energy for the past five years, they were able to help fund their wetlands, outdoor features and projects that are put towards their overall education for students.

“Having a basic passion for the environment and wanting to preserve the natural landscape and its beauty is amazing,” Rainey said. “You want to be able to protect things like wetlands to keep the environment safer for people down the line to use.”

Ella Katona is a reporter. Contact her at [email protected].