The spacecraft was expected to conclude its truncated, 10-day journey around 4 p.m. ET Thursday as it smashed into the Earth’s thick atmosphere over a remote area of the South Pacific Ocean, due east of Australia.

Astrobotic Technology, the Pittsburgh-based company that developed the Peregrine lander under a contract with NASA, confirmed the spacecraft’s demise, saying it lost contact with the vehicle moments before the planned reentry time, which “indicates the vehicle completed its controlled re-entry over open water in the South Pacific.”

However, the company added in a social media post, “we await independent confirmation from government entities.”

Officials from NASA and Astrobotic are expected to speak publicly on the mission during a news briefing at 1 p.m. ET Friday.

The failed mission is a setback for Astrobotic and NASA, whose overall goal is to create a stable of commercially developed, relatively cheap lunar landers capable of completing robotic missions to the moon as the space agency works toward a crewed lunar landing later this decade.

Critical setbacks after launch

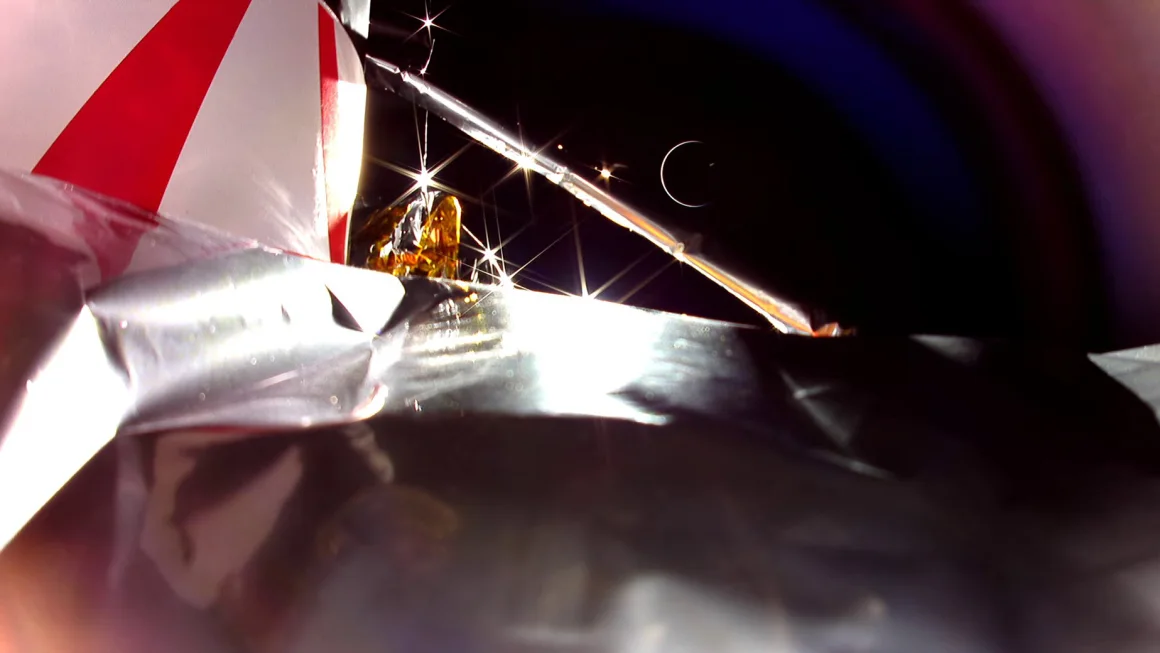

The Peregrine lander launched January 8 atop a Vulcan Centaur rocket, a new vehicle developed by United Launch Alliance, a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing.

The launch went off without a hitch, safely delivering the Peregrine lander into Earth’s orbit on a path toward the moon. If the spacecraft had been successful in reaching the lunar surface, it would have been the first US mission to soft-land on the moon since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

But hours into its solo flight, the Peregrine lander encountered critical setbacks. Astrobotic confirmed the spacecraft suffered a severe issue with its onboard propulsion systems and was leaking fuel, leaving the lander without enough gas to make a soft touchdown on the moon.

Astrobotic then shifted course. The company directed the spacecraft to operate more like a satellite, testing its onboard scientific instruments and other systems as it flew thousands of miles through the void.

Ultimately, Astrobotic determined that it would dispose of the vehicle by crashing it into Earth’s atmosphere at high speeds.

What Peregrine’s failure means

The loss of the Peregrine lander is a blow to Astrobotic and NASA.

A deal inked between the two organizations made this mission possible, with NASA handing over $108 million to aid Astrobotic with its development effort and fly five payloads. That price tag is a roughly 36% increase over the original contract value, with the deal being renegotiated amid pandemic-related supply chain issues, according to Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s science mission directorate.

The US space agency does not consider the Peregrine spacecraft its only option for conducting robotic research on the moon. NASA also has partnerships with three other companies developing robotic lunar landers — including Houston-based Intuitive Machines, which could launch its first mission in mid-February.

Through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, NASA designed those lunar lander contracts as “fixed price” agreements, meaning the space agency hands over one lump sum of money rather than continuing to pay a company throughout the development process as hiccups arise.

“This is one of many relatively cheap missions that are going to be sent to the surface of the moon to try to break the paradigm to try to get to a new price point,” Thornton told CNN earlier this month.

The deal is also structured so that the companies maintain complete ownership over their own vehicles, and NASA becomes just one of many customers flying cargo on the landers.

A proving ground for commercial lunar landers

A private lunar lander has never safely reached the moon’s surface — though other companies have tried. In 2019, a spacecraft built by Israel-based company SpaceIL smashed into the moon during a landing attempt. And again in 2023, Japan-based company Ispace lost control of its lander as it careened toward the moon’s surface.

SpaceIL, Ispace and Astrobotic all have roots in the same competition: the Google Lunar X Prize, which ran from 2007 to 2018 and offered a company that could reach the moon a $20 million grand prize. But X Prize concluded with no winner since none of the teams had launched by the final deadline.

Whether a commercially developed lunar lander can reach the moon’s surface remains to be seen — and perhaps an even more intriguing question is whether moon missions offer a financially sustainable business model for these companies.

Apart from money from NASA and other government space agencies, Astrobotic’s revenue for the Peregrine mission was generated by partnerships that included space burial companies that send human remains to the moon as well as packaged trinkets, plaques, a bitcoin, and other commemorative objects for customers.

Astrobotic’s Thornton admitted to reporters that the Peregrine mission cost his company more money than it made. However, a failure would not mean the end for Astrobotic, he said in remarks to CNN.

“It’s certainly going to have some impact on our relationships and our ability to secure additional missions in the future,” Thornton said on January 2. “It certainly wouldn’t be the end of the business, but it would certainly be challenging.

“We’re in a high-risk space venture, and this is just the nature of space businesses.”

Astrobotic already has a contract to fly another robotic lunar lander mission for NASA later this year. Called Griffin, that lander — a larger model than Peregrine — will aim to put a rover near the moon’s south pole.