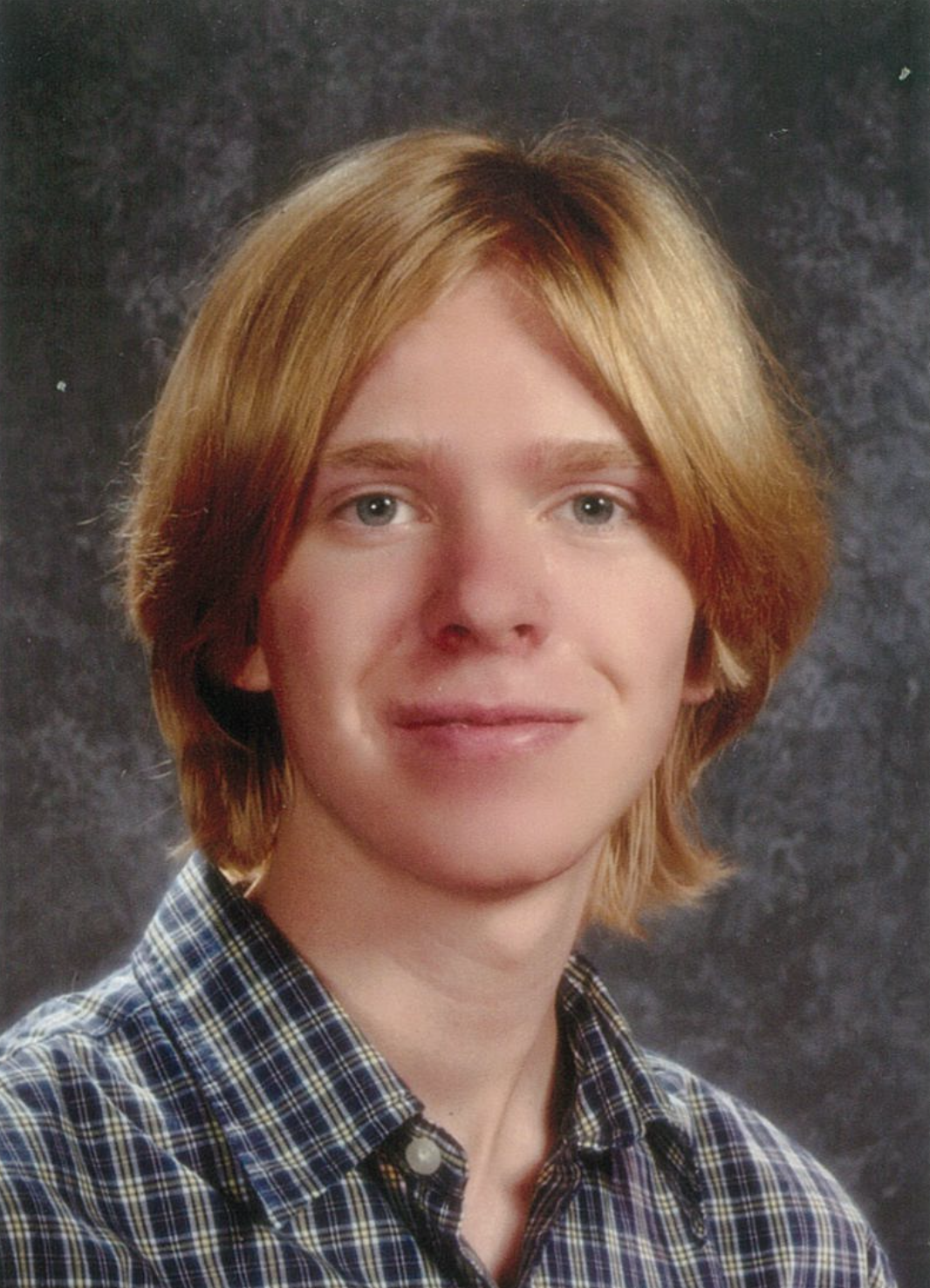

In December 2006, Brant Clark went to a party at a friend’s house. It was the 17-year-old’s winter break. He would be graduating high school soon, and like many teenagers, he enjoyed smoking cannabis socially.

Brant excelled in school and planned to attend college in the fall. He mowed lawns in his neighborhood and worked part-time as a busboy.

“He was the joy of my life,” said Ann Clark, his mother, “and then things went terribly wrong.”

When Brant returned home the next morning, his mother said something had noticeably changed in him. He had not slept all night, he told his mother, and he expressed a deep sense of emptiness and hopelessness. Over and over, he told his mother he made a mistake by smoking.

Two days later, his mother took him to the ER, and from there he went to an adolescent psychiatric care unit for help.

Three weeks later, Brant took his own life.

“I damned myself to hell,” he wrote in a note left behind. “I can only help my friends and pray. I killed my memory for no reason — now I’m just a burnt out star. I bit off more truth than I could handle. My eyes — I killed them. I shouldn’t let them open anymore — I’m a ghost. Why? No reason.”

According to Ann, Brant’s doctor said he experienced cannabis-induced psychosis. Brant believed God was angry at him for smoking marijuana, started reading the Bible obsessively and even thought he was the second coming of Christ.

“Sometimes those problems have resolved in a matter of months or a year, after the person has stopped using cannabis,” said Dr. David Streem, Cleveland Clinic Lutheran Hospital’s chief of psychiatry and medical director of the Alcohol and Drug Recovery Center. “Sometimes they don’t, and the person has lifelong psychotic symptoms as a result of cannabis.”

Some patients experience hallucinations that involve voices commenting on a person’s actions or saying insulting things about the person. Others experience paranoia such as delusions that they are being watched or are incapable of certain things.

According to one study, 30% of cases of schizophrenia among men aged 21–30 were linked to cannabis use disorder.

“You’re playing Russian roulette with your brain,” said Lori Robinson, director of Moms Strong, a parent support group that aims to educate families and young people that cannabis is not safe for everyone.

In 2009, Lori’s 23-year-old son Shane had just married his longtime girlfriend. Shane was a handsome, 6’4” young man with a “zest for life,” his mother remembered.

That same year, he suffered a knee injury while wakeboarding. While recovering from surgery, Shane developed an intolerance to his pain medications and started using cannabis. Despite his parents’ concerns, he insisted it was a harmless herb that helped manage his pain.

Then, Lori got a call that Shane was not acting himself and had been taken to a hospital. When she arrived, medical staff were already releasing Shane, unable to hold him because he did not pose a danger toward himself or others.

As she and her husband drove Shane home, he asked them if they saw the bombed-out buildings and said he needed to save President Barack Obama. At one point, he attempted to jump out of the moving car.

“I kept thinking, ‘Who is this imposter? It’s an alien. This is not my kid,’” Lori said.

Ultimately, Lori was able to admit her son into a private psychiatric hospital. There, Lori said Shane attempted to escape and had to be sedated by the medical team.

“He was very physically active, and very gregarious, outgoing, loved by pretty much everyone that ever met him,” Lori said. “A really good kid, and unfortunately, he made a fatal mistake.”

After a two-year cycle of relapse and hospitalization, including a second psychotic break, Shane took his own life at 25 years old.

Both of Shane’s out-patient psychologists were skeptical cannabis could cause psychosis, and cannabis-induced disorders would not be added until 2013 to the 5th edition of the DSM 5.

Neither Shane nor Brant had a previous mental health diagnosis, and there was no history of mental illness in either’s family. Their symptoms appeared rapidly.

For many years, the mothers said they felt like their concerns over cannabis were ignored.

Just three days after Brant’s death, Ann distributed flyers at his funeral sharing the role cannabis played in his suicide. The reactions varied, with the woman seated next to her calling the flyers crazy.

“In Boulder, and to this day, most people think marijuana is harmless,” Ann said.

Since their sons’ deaths, Ann and Lori have worked to raise awareness for what they see as a deadly drug. Often, they have been met with deaf ears.

But as cannabis becomes more widely available, with Ohio becoming the 24th state to legalize the drug last year, medical professionals are growing concerned over how cannabis affects young minds.

“Cannabis-induced psychosis is a public health concern,” said Samantha Holmes, project coordinator for Cleveland Department of Health’s Office of Mental Health and Addiction Recovery.

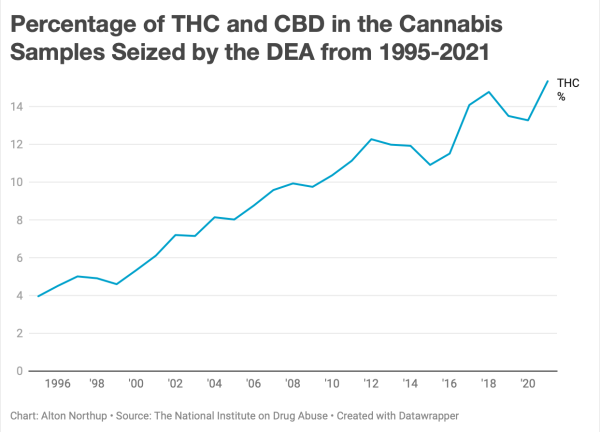

Both Holmes and Streem attribute the cause of cannabis-induced psychosis to the increase in THC content. According to a study from Yale School of Medicine, the average THC content in cannabis seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration increased by 425% between 1995 and 2017.

Streem said the risk of developing psychotic symptoms from cannabis with THC content around 10% is quite low. But in the recreational market, dispensaries often sell cannabis with THC content at 25% or 30%. Ohio law requires that THC content in cannabis should not exceed 35% for plant material or 70% for manufactured products.

Streem said he did not encounter a single case of cannabis-induced psychosis during the first 25 years of his practice. Now, he sees one almost every year.

“The risk of developing psychosis goes up as the percent THC in the cannabis goes up,” Streem said.

Those with a genetic predisposition to mental illness may be at a greater risk to developing cannabis-induced psychosis, Streem said. But he cautioned even those without a family history of mental illness, like Brant and Shane, are not safe.

“My recommendation is that there is no redeeming health value to cannabis that justifies or offsets the risk,” Streem said. “The risk is much higher than it was 20 years ago.”

Alton Northup is editor-in-chief. Contact him at [email protected].

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Gregory Clark • Oct 31, 2024 at 8:16 am

I have been accounted for smoker since 15 it’s the best medicine I’ve ever had that I am so sorry for your losses this is got to do with concentrates and things and and things that are just not right there’s something wrong and I don’t know what it is but it’s not cannabis not for me and not for millions and millions of others I am so sorry for your losses I’m a pastor and I say if you’re not going to do any drugs don’t do them if you’re going to smoke something the killer is tobacco tobacco was killed more people than all world wars combined ! I think there’s a lot more that needs to be done please watch the movie The God plant and understand that millions of people are being helped with convulsions it does far more good than it does bad and I am so sorry for your loss and in the name of our father been a beautiful way. ! And bless your sons this could be big business that I don’t know I’m not a doctor but I will tell you I got to say it again I’ve been Amsterdam five times it’s the best medicine I’m only on blood pressure medicine I was on every painkiller there was I’ve done every drug on the planet and the only one that’s any good is marijuana and I’m sorry for your loss!

Colleen • Aug 17, 2024 at 3:20 pm

My son started using cannabis at the age of 15, from then on it ruined his whole being. Countless trips to psychiatrist after psychiatrist.by the time he turned 20 he had 3 children unable to take care of himself let alone his children. After he turned 18 he tried getting himself help through different mental health institutes including lutheran and southwest and a long stay in van wert ohio treatment center. There was no one that could help him or figure out how to help him, he begged for help. At the age of 21 this past march he took his own life. There is not enough talk about the effects of cannabis as a child or young adult. How many parents have to go through losing a child like this

Matt Poling MD • Jul 11, 2024 at 11:06 am

I’m just a family physician in a college town and I’ve seen this multiple times. Young people supporting marijuana legalization makes much sense as chickens supporting Colonel Sanders.

Matt Brown • Jul 11, 2024 at 12:43 pm

Literally millions and millions of people consume marijuana without ill effects.

For decades and decades.

Ask Willie Nelson.

Physicians that overexaggerate and insert their biased opinion over unbiased research and evidence against their extreme opinion should have their licenses pulled.

Aubree A Adams • Jul 11, 2024 at 8:40 pm

Dear Matt Brown,

You’re an entitled, selfish jerk. How dare you deny and minimize Brant and Shane’s life. You’re lucky your marijuana use is only you to act like a jerk and that you haven’t experienced psychosis.