The bustling city of Shanghai marks national celebrations with world-famous light shows, illuminating its skyscrapers with dazzling colors, like beacons of Chinese innovation.

It is here that scientists and engineers work around the clock to pursue the next big thing in global tech, from 6G internet and advanced AI to next-generation robotics. It’s also here, on an unassuming downtown street, a small start-up called Energy Singularity is working on something extraordinary: nuclear fusion energy.

US companies and industry experts are worried America is losing its decades-long lead in the race to master this near-limitless form of clean energy, as new fusion companies sprout across China, and Beijing outspends DC.

Nuclear fusion, the process that powers the sun and other stars, is painstakingly finicky to replicate on Earth. Many countries have achieved fusion reactions, but sustaining them for long enough to use in the real world remains elusive.

Mastering fusion is an enticing prospect that promises wealth and global influence to whichever country tames it first.

The prize of this energy is its sheer efficiency. A controlled fusion reaction releases around four million times more energy than burning coal, oil or gas, and four times more than fission, the kind of nuclear energy used today. It won’t be developed in time to fight climate change in this crucial decade, but it could be the solution to future warming.

The Chinese government is pouring money into the venture, putting an estimated $1 billion to $1.5 billion annually into fusion, according to Jean Paul Allain, who leads the US Energy Department’s Office of Fusion Energy Sciences. In comparison, the Biden administration has spent around $800 million a year.

“To me, what’s more important than the number, it’s actually how fast they’re doing this,” Allain told CNN.

Private businesses in both countries are optimistic, saying they can get fusion power on the grid by the mid-2030s, despite the enormous technical challenges that remain.

The US was among the world’s first to move on the futuristic gambit, working on fusion research in earnest since the early 1950s. China’s foray into fusion came later that decade. More recently, its pace has ratcheted up: Since 2015, China’s fusion patents have surged, and it now has more than any other country, according to industry data published by Nikkei.

Energy Singularity, the start-up in Shanghai, is just one example of China’s warp speed.

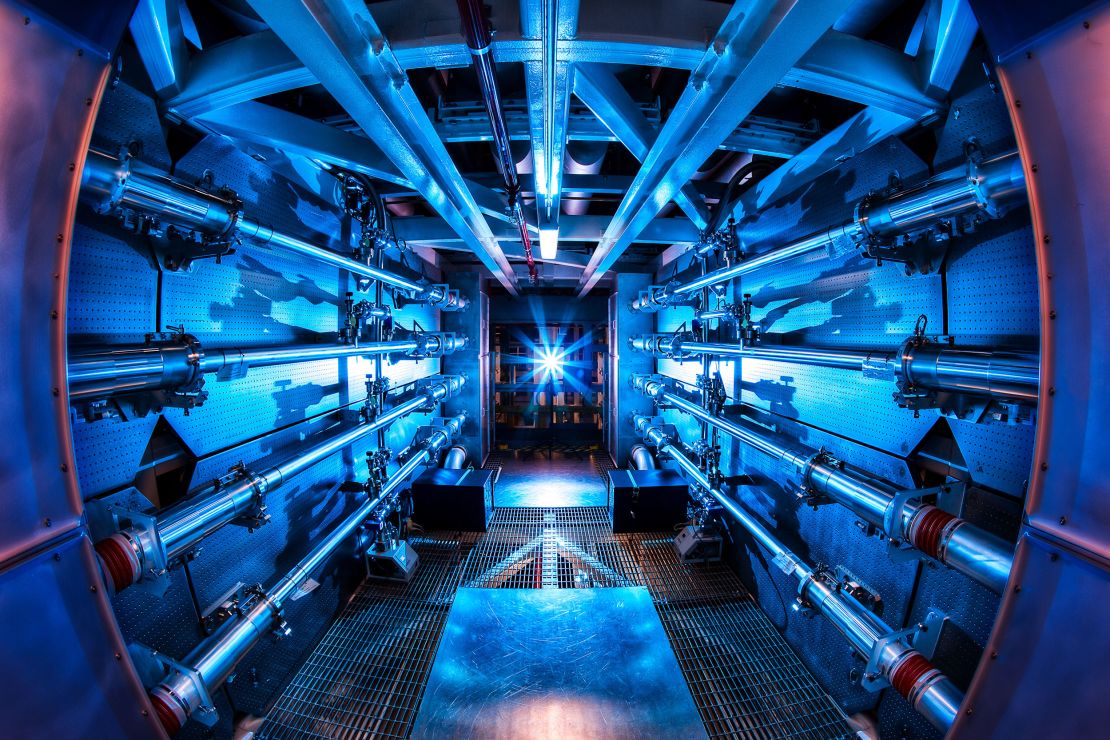

It built its own tokamak in the three years since it was established, faster than any comparable reactor has ever been built. A tokamak is a highly complex cylindrical or donut-shaped machine that heats hydrogen to extreme temperatures, forming a soup-like plasma in which the nuclear fusion reaction occurs.

For a fledgling company working on one of the world’s most difficult physics puzzles, Energy Singularity is incredibly optimistic. It has reason to be: It has received more than $112 million in private investment and it has also achieved a world first — its current tokamak is the only one to have used advanced magnets in a plasma experiment.

Known as high-temperature superconductors, the magnets are stronger than the copper ones used in older tokamaks. According to MIT scientists researching the same technology, they allow for smaller tokamaks that can generate as much fusion energy as larger ones, and they can better confine plasma.

The company is planning to build a second-generation tokamak to prove its methods are commercially viable by 2027, and it expects a third-gen device that can feed power to the grid before 2035, the company said.

In contrast, the tokamaks in the US are aging, said Andrew Holland, CEO of the Washington, DC-based Fusion Industry Association. As a result, the US relies on its allies’ machines in Japan, Europe and the UK to further its research.

Holland pointed to a new $570 million fusion research park in eastern China under construction, called CRAFT, on track to be completed next year.

“We don’t have anything like that,” he told CNN. “The Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory has been upgrading its tokamak for 10 years now. The other operating tokamak in the United States, the DIII-D, is a 30-year-old machine. There’s no modern fusion facilities at American national labs.”

There’s a growing unease in the US industry that China is beating America at its own game. Some of the next-generation tokamaks China has built, or plans to, are essentially “copies” of US designs and use components that resemble those made in America, Holland said.