Former professor writes book about Vietnam War, PTSD

March 13, 2019

In the winter of 2015, Barbara Child was seeking clarity. Why had she been plagued with phobias for most of her life? Was there a meaning behind them? She signed up for Pacifica Graduate Institute’s four-week-long course on analytical psychology called, “Alchemy, Romanticism, The Red Book and the New Myth of Our Time” in hopes she’d find the answers she needed.

The book “Memories of a Vietnam Veteran” is the result of analysis Child underwent during the course. As she visited with a psychologist for Jungian analysis (an analytical form of talk therapy designed to bring together the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind) during the course, Child’s memories led the way to her writing the book about her late partner Alan Morris, and his own recounting of his time spent in Vietnam.

“I had lived with the memories of my partner Alan Morris for two decades after his suicide,” Child said. “And for the 10 years we were together before he died, I had lived with the results of his memories of his experience as a medic in Vietnam. And then I began an analysis with a Jungian psychologist. I was planning to address issues that had nothing to do with Alan, but it was as if my dreams had their own agenda.”

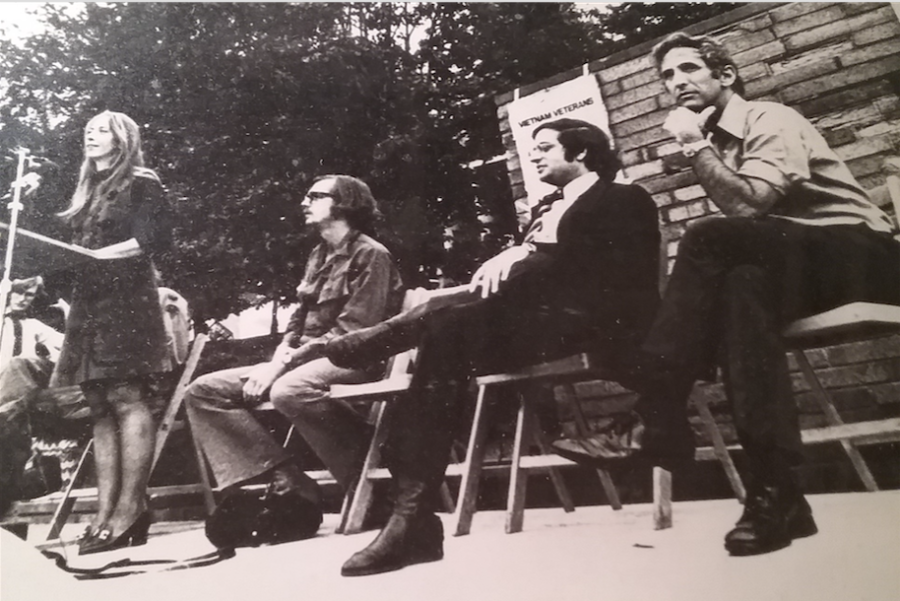

Child first met Morris in 1972 while she was teaching in the Kent State English department. She chaired the Portage County American Civil Liberties Union and he was a leading member of the Kent Vietnam Veterans Against the War. But the pair didn’t become close until the summer of 1986 when Morris called Child out of the blue at her house in Gainesville, Florida. She remembered him from her days in Kent, and said yes when he’d asked to visit her.

“One fine day during the summer of 1986, well over a decade after I had last seen him, Alan Morris called me and asked if he could come visit, and then appeared in my office,” Child wrote in the memoir.

Soon after his visit to Gainesville, Morris moved down. What followed was a 10 year relationship that was often haunted by Morris’s struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by his years in Vietnam.

While Child was away in California for her graduation from ministry school, Morris ended his struggle with PTSD in May of 1996 when he committed suicide.

The story of Child and Morris’ time together is told in the book’s first part, “A Lifetime is Too Narrow to Understand It All.” In the same section, Child ties in writings done by Morris recounting his time in the war as a medic to illustrate how much his time in Vietnam affected not only him, but their time together.

Part two is called, “I Will Wait for You,” and offers insight on what it’s like to endure a partner’s suicide, and takes you through Child’s dream work with Jungian analyst Tom Elsner during her four-week course at Pacifica.

The memoir is accompanied by a prologue and epilogue that carry heavy importance. The prologue sets the premise for the memoir and introduces both Child and Morris at the very beginning of their story at their first meeting at Kent State.

In the prologue, Child mentions a letter she wrote to Morris during the time she was studying in California and he was living in Florida. The letter was a product of Child’s seminary course on war, and titled “An Open Letter to a Vietnam Veteran.” Little did she know then, the letter would expand to something much bigger almost twenty five years later.

The epilogue adds a special kind of closure to the memoir by bringing the readers to Child’s present-day life, and how it relates to having known Morris and having lost him.

In addition to the prologue and epilogue, there’s a hopeful afterword. In it, Child recounts her recent trip to Vietnam. In November 2018, she traveled along with a friend and ministerial colleague, Jan Carlsson-Bull on a healing trip to Vietnam. The trip was led by Edward Tick, a healer, psychotherapist, writer and educator, who had been guiding groups of veterans and loved ones of veterans on healing journeys to Vietnam since November of 2000. What Child was searching for when she traveled to Vietnam, she wasn’t quite sure.

“When I did go, (to Vietnam) I was not consciously searching for any particular thing,” she said. “As a result, even though I could not have known to say so at the time, I had reached a point where not searching allowed me to be open to whatever might present itself. What presented itself, unbidden, unsought, was release.”

“Memories of a Vietnam Veteran” uses Child’s personal story and relationship with a Vietnam veteran to enlighten readers on the issues that come along with being in war. She hopes by sharing her and Morris’s story, readers will finish the book with a better understanding of just how harmful war is on the people involved.

“I hope readers will take away a deeper understanding of the ravages of war on the body, mind and soul of those who serve in battle zones,” Child said. “I hope readers will see that writing this off as some vague medical condition called PTSD is a travesty of the truth and have a new appreciation of the complexity of human relationships and how much more important meaning than ‘happiness.’”

Toward the end of the book, we are given an excerpt from the poem “Having Loved Enough” by Mark Nepo. The excerpt embodies Child’s outlook moving forward.

Having loved enough and lost enough,

I’m no longer searching,

Just opening…

Abigail Miller is a feature writer. You can contact her at [email protected].