What we see in the mirror: how gender dysphoria and body dysmorphia affect students

December 5, 2021

Social media and internet culture have allowed members of Gen Z to make strides in sharing their stories. From TikToks documenting untold queer history to recommending the best first date spots for queer people, an abundance of knowledge is being collected. But what about the issues that don’t see the light of day?

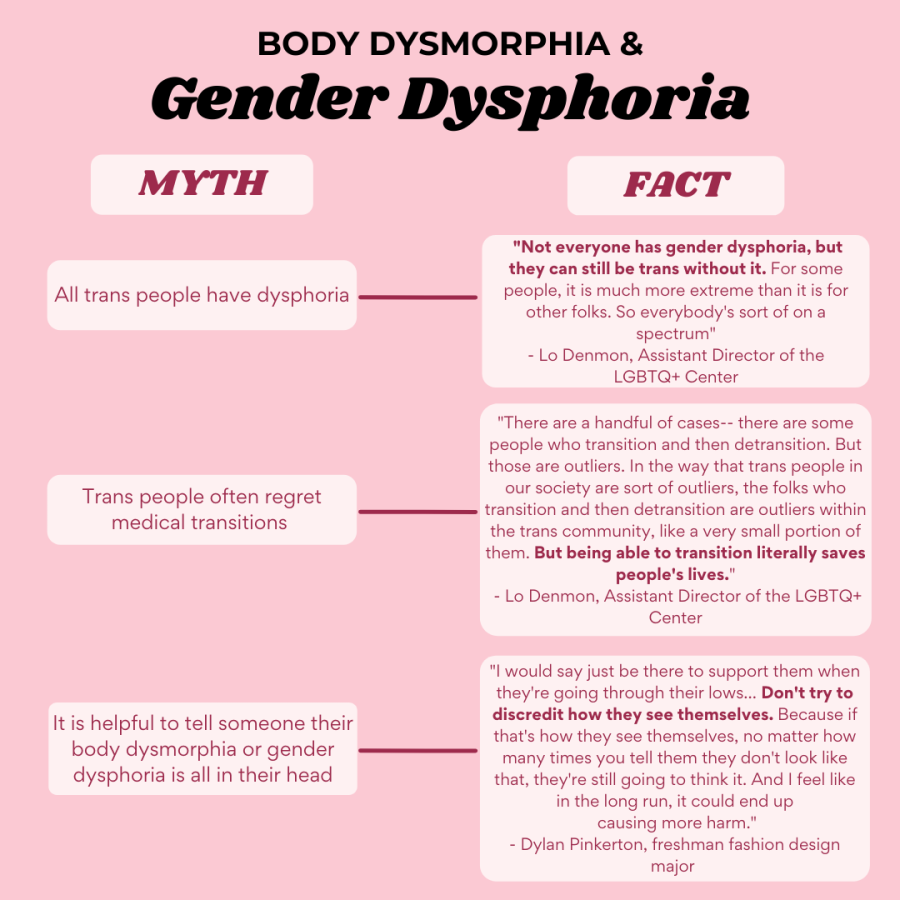

For example, gender dysphoria— the discomfort one experiences because their outward appearance and the way they are perceived do not align with their gender identity.

Although gender dysphoria is often compared to body dysmorphia, the difference is important to note.

“Body dysmorphia is a completely different thing,” Kent State psychologist Jennifer Grzegorek said. “It’s in the general category of obsessive-compulsive conditions and related conditions. So, it tends to have an anxiety component to it where a person is preoccupied with what they perceive as a flaw about their body.”

Gender dysphoria, on the other hand, is less about a perceived flaw and more about a disconnect between gender identity and gender expression. This disconnect is influenced not only by an individual’s personal perception of themself, but also by society’s standards of how someone of a specific gender should look.

“For a lot of folks that can also mean extreme discomfort with the shape of their face, distribution of body fat on their body, whether or not they have a chest, whether or not they have certain reproductive organs,” said Lo Denmon, the assistant director of the LGBTQ+ Center.

In some cases, social transition can be a way to relieve dysphoria – changing your clothing, your hairstyle, your name or your pronouns. Other options may even include legal or medical transitions.

Freshman fashion design major Dylan Pinkerton, also known as Kent drag queen Frutisha Punch, recommends drag as a way to play with gender expression.

“Because a majority of the time I do identify as more masculine, drag is an art form that I can express femininity through, and just have fun with it, and look a little dumb sometimes,” Pinkerton said. “So, it’s just like, I kind of party with it. And I think drag is a really good outlet for anybody who might be questioning their gender as a way to just express themselves as they want to see themselves.”

The media have a narrow viewpoint of what body dysmorphia and gender dysphoria can look like, and the depictions can be harmful. In particular, the way television details the transmasculine experience and binding for the first time is dangerous.

“In a lot of pop culture that gets used as symbolism. Like the slow wrapping of the chest, and it’s this big, dramatic thing,” Denmon said. “And Ace bandages are not good for you, they start to compress around your chest, and it makes it harder for you to breathe, they can damage internal organs. And some folks will get damage to their chests in a way that impacts their ability to get top surgery.”

Reinforcing these narratives also isolates individuals who don’t have similar lived experiences to those portrayed in the media. The internet primarily spotlights thin, white transmasculine people, Denmon said, but there is a world of people whose experiences are vastly different.

“[There are] plenty of trans women in the world,” they said. “So many trans femmes. Lots of people of color are trans. There are people who are not thin who are trans. There are people of different abilities who are still trans. But because we don’t see representation of them, we don’t talk about them.”

Because society continues to grasp onto the gender binary system, individuals with dysphoria try to understand their lived experiences through the lens of being cisgender, Denmon said.

“For some folks, it is hard to break away from that…Because they were told ‘No, this is who you are. Deal with it. ascribe to it.’ And it can feel really challenging to sort of fit into that. Until you realize that you don’t have to,” they said.

The pressure to conform to binary standards can be dangerous, and the lack of conversation, particularly in the queer community, leaves people in the dark.

“We don’t have enough of those conversations because we have to protect our wellness and protect ourselves from folks who wants to discredit. So, it’s a challenge to find community when you feel like you might be under threat all the time,” Denmon said.

And creating a safe space for queer people, especially those who experience gender dysphoria, is a journey in itself.

“It’s just good to go in with an open mind,” Pinkerton said. “When you think about gender, or body or whatever you are thinking about when it comes to people, be open-minded. You don’t know what people are dealing with inside their head, and you’re not going to know unless they tell you, so don’t assume.”

Reegan Saunders is a reporter. Contact them at [email protected].