Pulitzer Prize winning author Art Spiegelman discusses comics and identity

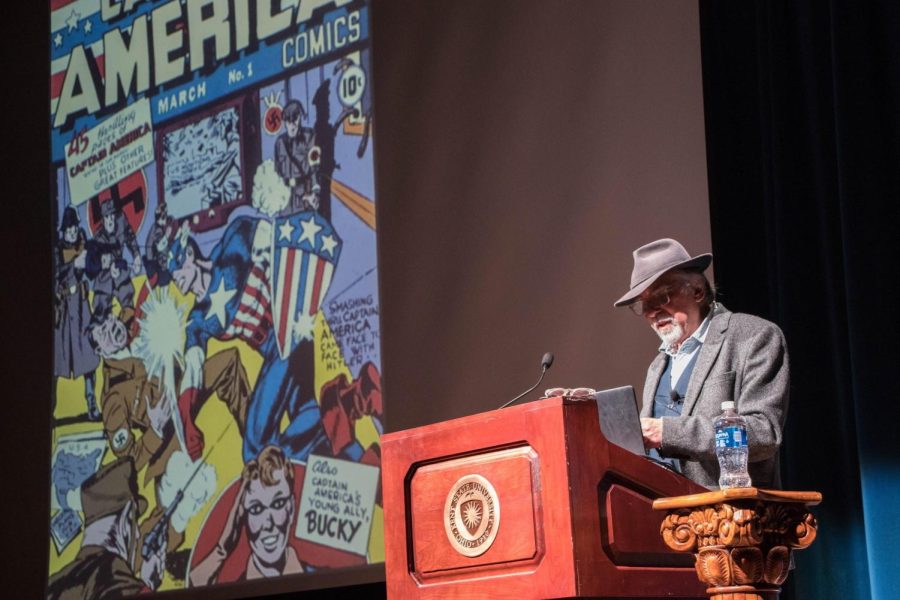

Pulitzer Prize winner, Art Spiegelman, discusses comic books during World War II at his program titled “Comix, Jews’n Art – Dun’t Esk” in the Kiva Tuesday, March 6.

March 7, 2018

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and graphic artist Art Spiegelman told students and members of the public just how comics, Jews and art align in a post-modernist world at the Kiva Tuesday.

Invited by Chaya Kessel, the director of the Jewish Studies Program, Spiegelman gave his free presentation titled “Comix, Jews ’n Art — Dun’t Esk.”

Spiegelman is best known for his highly acclaimed graphic novel and memoir, “Maus,” which won him a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

“I spent 13 years making ‘Maus,’ I spent the next 12 talking about ‘Maus’ to the public so I’m not sure what to do with comics, Jews and art,” he said.

Starting his career during the 1960s, Spiegelman went on to work for The New Yorker and is responsible for the creation of “Wacky Packages” and “Garbage Pail Kids.”

“Maus” is still an acclaimed memoir of Spiegelman’s father’s struggle during his time in a Nazi concentration camp, but the night wasn’t just about one award-winning piece.

Spiegelman warned the audience early in his presentation that the night would be spent discussing how exactly comics, Judaism and art (the practice and the man) have crossed paths in history and what their place in the world is today.

Spiegelman spent the better part of his public speaking time talking about the book since its publication.

Spiegelman explained how those topics made his head feel by playing a sound bite of the loud sound of glass breaking. A gag which he said was “a hint of all the facets” of his personality.

He said that he never aimed to create such a cultural statement with “Maus,” but rather to create a comic book long enough so that “it needed a bookmark and wanted to be reread,” a platform that didn’t have a strong foothold at the time.

To connect his style of comics with art and Judaism, Spiegelman said “comics are kind of the Yiddish of art,” as it operates as a vernacular, especially since the most popular comics back in the 1940s were those in the pages of newspapers.

Spiegelman went on to say to that while he finds himself to be Jewish by culture, he is not Jewish by faith like his father, the protagonist of “Maus.”

“I identify with the Judaism of Marx, both Karl and Groucho,” he said.

This introduced Spiegelman’s talking point on the current issue of identity politics and victim culture in the U.S. today. He cited a cover for The New Yorker he illustrated called “Family Values” where people of punk, hippy and beat culture sit around each other as a family of alienated outsiders — a group he said that he relates to.

“Ultimately, I identify most as a cartoonist-American rather than a Jewish-American,” Spiegelman said while going on to show a slide of a stereotypical Jewish caricature.

“This doesn’t mean I’m a self hating Jew. To quote Woody Allen, ‘I’m not a self hating Jew – I just hate myself.’”

Steven Selnik, a 40-year-long fan of comics, said his first time hearing Spiegelman in person was compelling and he was better than what he had assumed it to be.

“I thought he was going to be more of this poster boy for the Jewish arts but he was a cartoonist first and his heritage just happened to be a part of it,” Selnik said.

Despite this, Selnik is appreciative of what Spiegelman has done with his work.

“(Spiegelman) legitimized the art form to the masses, not only to the U.S., but to the world. It’s something that can be compelling or adult and not just a funny book or superheroes in tights,” he said.

Jarett Theberge is a visual arts reporter. Contact him at [email protected].