House GOP tax bill could leave graduates with financial burden

December 6, 2017

The GOP-majority House of Representatives passed the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” bill Nov. 16 implementing a sweeping overhaul of the tax code with a vote of 227-202. No Democrats and only 13 Republicans voted against the bill.

The policy has yet to be codified into law, as the U.S. Senate passed a different, yet largely similar tax bill Nov. 30. In the coming weeks, the two bills will be combined and reconciled before heading to President Donald Trump’s desk for final approval, with a stated goal by the Republican president of finalization before Christmas.

The House bill has not gone without criticism, with opponents citing a massive increase to the federal deficit; a report from the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the bill would add $1.487 trillion to the national deficit.

Another facet of the bill, the attempted elimination of the individual insurance mandate, which is a product of the Affordable Care Act, is another reason opponents say the bill should not be passed.

When it comes to education, however, criticism of the bill is largely centered on a provision that would begin counting the value of tuition waivers for graduate students as taxable income.

“Right now, students are taxed on the income part of that, so, on the stipend part,” said Melody Tankersley, the senior associate provost and dean of graduate studies. “But the tuition is not treated as income. And what the proposed legislation would do, would be to put that in as income as well. So instead of just being taxed on (their stipend), they would be taxed on the whole package.”

At most, public university stipends are paid to graduate students who participate in assistantships, whether that be teaching courses in their discipline, doing research in a lab or working with the administrators in their department.

In a public letter sent to Ohio congressional representatives, Kent State President Beverly Warren expressed concerns with the provision, saying the following to demonstrate the value graduate students have to the university:

“Taxing graduate student stipends and waivers will materially impact Kent State University’s ability to advance our research enterprise, which depends on recruiting and retaining talented, research-focused graduate assistants and post-doctoral students. STEM education and research contribute to the economic vitality of our state and our nation. Taxing these earnings creates an undue burden on students whose contributions fuel our research growth and productivity.”

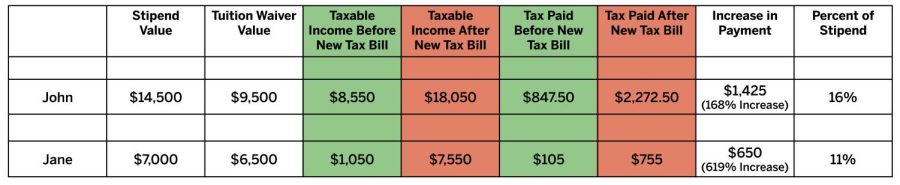

In the letter was a chart produced by Tim Rose, the Graduate Student Senate advocacy chair, demonstrating the potential impact the provision could have on a graduate student’s net income, or income after taxes.

For a hypothetical graduate student with a stipend of $7,000 with tuition valued at $6,500, they could see an increase in taxes paid from $105 to $755 — a 619 percent increase and 11 percent of their total yearly income.

Paula DiVencenzo, a tax manager in the business and finance department, said while the numbers aren’t a full reflection of the impact the House bill could have on graduate students’ income, it could still be harmful to their financial situation.

“It is not clear to me if the analysis reflected the increased standard deduction and the loss of personal exemptions and the change in tax rates,” DiVencenzo said via email. “For the average individual, the net gain would be about $2,000 (roughly $6,000 increase in standard deduction with $4,000 loss in personal exemption).”

The Internal Revenue Service describes standard deductions as a reduction in taxable income, which brings down the amount an individual pays in taxes at the end of the year.

“Regardless, I would still expect most graduate assistants/graduate students to have an increase in their tax liability as a result of the house provisions,” DiVencenzo said.

With the provision having the potential for an impact on graduate students’ financial stability beyond the cushion of standard deductions, Tankersley believes it could end in more people declining to continue their education into graduate studies.

“We, as a global society, need people who have advanced learning, advanced training, in all walks of our lives,” Tankersley said. “And the kinds of skills and experiences that people need every year increasingly becomes more demanding. This punishes people for advancing in their education.”

Tankersley believes, if the provision passes, it will be detrimental to graduate education across the country.

“So this would drastically, across the nation, decrease the number of students seeking advanced degrees, which ultimately hurts us,” Tankersley said. “Hurts us as a society, it hurts us economically, it hurts innovation, it hurts design and it hurts everything we want to continue to grow.”

Mark Rhodes, the executive chair of Graduate Student Senate, who is in his fifth year at Kent State and currently a Ph.D. candidate in the geography department, agreed, saying the provision could cripple graduate education in the United States.

“The idea that we’d be taxed on this tuition waiver as if it was income on this money that we never see, is ridiculous,” Rhodes said. “It will end up being that … richest individuals would be able to attend graduate school. Otherwise, you’d have to take out a loan, which graduate students, for the majority, don’t take out loans. The ideal situation is you’re able to get by on this meager amount — of course it doesn’t always happen — but that’s the ideal: You don’t want to pay for graduate school. That’s the first thing any professor will ever tell you, is ‘Don’t pay for graduate school.’”

The other possibility Rhodes mentions would be for universities to increase stipends.

“The university would end up losing a lot of money in order to increase stipends to compensate for this loss,” Rhodes said. “Without the number of graduate students, we have over 1,000 graduate assistants on this campus, … (the university) would have to rely on an increase in adjuncts, which nobody wants to see happen, or faculty — which we can’t afford, or administration — which we can’t afford.”

Kate Klonowski, vice executive chair of the Graduate Student Senate and a graduate student in the College of Education, Health and Human Services, expressed concerns for low-income people pursuing post-graduate education.

“Some people would argue, ‘Well, if you want to go to grad school you should be able to pay for it,’ but that’s not the case for many of us,” Klonowski said. “And those of us who are here for various reasons are … taking a great deal of financial sacrifice to be here anyway. Giving up decently paying jobs or are trying to work jobs on top of that, then we’re trying to make ends meet. So it’s detrimental, and basically we’re looking at taxing things that eventually, at the end of the day, are not going to really help the country financially.”

Through the criticisms, little has been offered to defend the provision. A spokesman from the House Committee on Education and the Workforce told the New York Times the bill would “provide more Americans with more opportunities of their choosing, including continuing education.”

Aside from that statement, another spokeswoman from the House Ways and Means Committee said, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is focused on providing tax relief and increasing take-home pay for Americans of all walks of life — including people working to pay off tuition and other education costs,” and little has been done to defend the provision that has seen increasing pushback since the bill was made public.

There is some hope for graduate students residing in the process of reconciliation: The Senate’s version of the bill does not feature this provision, and in the process of merging the two bills, the tuition waiver tax could be dropped.

Rhodes, however, said the Graduate Student Senate still intends to fight against it, mostly by informing people of the potential consequences. Graduate Student Senate launched a campaign in recent weeks to accomplish this, reaching out to Ohio Gov. John Kasich, Ohio Sens. Rob Portman and Sherrod Brown and the House representatives for each district a Kent State regional campus exists within.

“We’re just trying to get the word out, and get as many people to know about it and know what this is gonna do,” Rhodes said. “And we think that, if they know what it’s going to do, they won’t go through with it and in the compromise between the House and the Senate, they’ll keep the Senate’s portion.”

Klonowski also said the plan is not taking into account the long-term future of education.

“It looks very much like an attack on intelligence, on education, and that’s what I would look at it as,” Klonowski said. “From a fiscally responsible point of view, not investing in the future of education is an incredibly short-sighted, selfish act on anyone’s watch, and I think it’s going to manifest itself in very painful ways for the country and for the world.”

Nicholas Hunter is the academic affairs reporter. Contact him at [email protected].