From health to obsession: When clean eating goes too far

October 25, 2017

Deanna Lavanty was hungry all the time.

She started to feel this way after cutting out fat in her diet. In order to supplement her lack of nutrition, she found herself eating up to nine bowls of cereal per day. Pair this with quinoa, fruits, vegetables and lean, dry-cooked protein, and she thought she was living a healthy lifestyle. But eating to these extremes had the opposite effect.

“I would sit down in a restaurant, read the menu and leave because there was nothing I could eat,” said Lavanty, who is now a Kent State dietitian. “If friends were with me, they’d leave the restaurant too, not willingly though. My thoughts were preoccupied with food as I continued omitting fat from my diet. I was anxious. I became depressed. I was lethargic, and eventually my menstrual cycle stopped.”

Orthorexia nervosa, though not formally recognized as a clinical eating disorder in the fifth addition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, has been a condition discussed among the medical community since the late 1990s, Lavanty said.

“For people with orthorexia, eating healthily has become an extreme, obsessive, psychologically limiting and sometimes physically dangerous disorder, related to, but quite distinct from anorexia,” said Steven Bratman, the medical director of Prima Health Care based out of Northeast Ohio. He coined the term orthorexia in 1996.

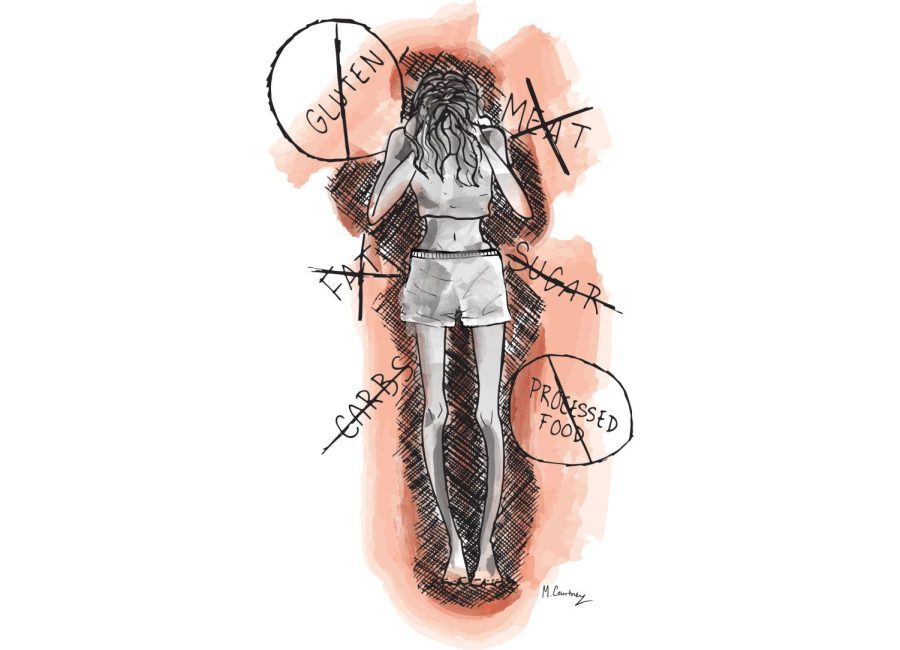

While anorexia nervosa and bulimia cause those suffering from the disorder to obsess over weight and calories, orthorexia is the fixation of eating only healthy, or so-called “pure,” foods.

The psychological condition has been popularized in recent years due to organic and whole food trends, and it can be easy for people to succumb to this disorder. What normally starts out as an innocent attempt at eating healthy can turn into food choices becoming so restrictive it can have serious health consequences.

Lavanty decided to eat less meat because she had a hard time identifying it in the cafeteria in college. With all of the new knowledge on fats coming out, she began to cut that out of her diet as well.

“To achieve that took discipline, but the discipline was really a response to what became almost a phobia of dietary fat,” Lavanty said.

It follows the same pattern as any other eating disorder. Kelsey Ravin, a Kent State alumna, wrote a thesis on orthorexia during her time as an undergraduate.

She found the characteristics of people suffering from orthorexia are similar to those with eating disorders. People develop depression, mood swings and anxiety. They constantly think about food every day and feel guilty when they eat food outside of their diet. Eating out becomes almost impossible, which affects personal relationships.

“Every day is a chance to eat right, be good, rise above others in dietary prowess and self-punish if temptation wins,” said Karin Kratina, a registered dietitian for the National Eating Disorders Association.

When Lavanty went to the doctor for her amenorrhea, which is one or more missed menstrual periods, she was referred to a dietitian. This confused her because she thought her diet was perfect.

After filling out a three-day food log, the dietitian was impressed with the types of foods Lavanty was consuming, except for one problem: no fats. She described to her the difference in healthy and unhealthy fats and recommended 70 grams per day.

“There was no way, after four years of avoiding fat like the plague,” Lavanty said, “and practically developing a phobia against it, that I was going to consume 70 grams of fat per day.”

Some studies are finding that media has a big role in orthorexia. The rise of lifestyle books, magazines and websites producing misinformation about health can lead to unhealthy diets consisting of only certain food groups.

“People with eating disorders know a lot about food and food science,” said Marjorie Nolan Cohn, former Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics spokesperson. “They don’t always have accurate information. Sometimes their sources are magazines or blogs that might not be reputable.”

However, when the dietitian asked her to try out her method for just one month, Lavanty changed her mind.

“I unintentionally lost ten pounds,” she said. “I was energetic and, eventually, the amenorrhea was resolved. I never felt better, physically and mentally. It became obvious to me that food has a medicinal effect on the body.”

Unlike other eating disorders, orthorexia equally affects both men and women.

“Society pushes healthy eating and thinness, so it’s easy for many to not realize how problematic this behavior can become,” Bratman said.

Some medical community members are now pushing to get orthorexia classified as an eating disorder, but it may take time, as more research still needs to be developed around the issue.

“Like so many girls and women, I’d had an eating disorder when I was younger, from age 10 until I went vegan when I was 20,” Ravin said. “If you really want to psychoanalyze that, I imagine I just found a new way to have control over my eating behaviors.”

One of the best ways to avoid orthorexia is to know what a truly healthy diet looks like.

“Knowledge is power,” Lavanty said. “Go to experts to learn how to be healthy, rather than succumbing to what you read on the internet. Striving to be healthy is good, but obsessing over it will affect your mental health in the long run.”

She encourages people suffering from orthorexia or other eating disorders to see a skilled practitioner.

“See a dietitian to develop a diet that is right for you,” she said. “See a personal trainer for advice on fitness. Your mind and body will thank you.”

Dylan Thacker is the recreation and fitness reporter. Contact him at [email protected].