Keeping up with compliance

May 3, 2017

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 mandates that public universities report sexual discrimination, assault and harassment on campus. When universities do not comply with these regulations and Title IX complaints are not reported, cases can end up in court.

To view an interactive Title IX complaint process, click here.

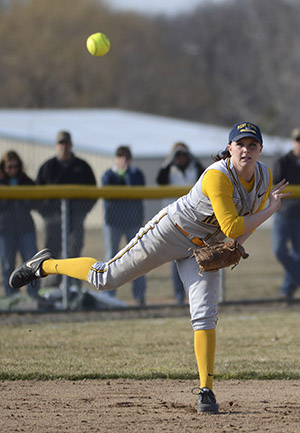

In February 2016, former Kent State softball player Lauren Kesterson filed a complaint in an Ohio district court. Kesterson alleged former baseball player Tucker Linder raped her. Linder was the son of Karen Linder, then coach of Kesterson’s softball team. The crux of the case rests in the university’s non-compliance with Title IX reporting procedures.

Kesterson claimed she told coach Linder about the rape in mid-May 2014 and tried lodging a formal complaint. Linder acknowledged that she must report Kesterson’s complaint under the Title IX policy at Kent State, but is quoted in the court case as saying: “I would appreciate if you would not tell anybody else, and that we keep this between the people that know.”

Linder said her son, Tucker, “is not right,” citing a previous alcohol-related arrest that past St. Patrick’s Day.

Linder did not comply with Kent State’s Title IX procedure and never filed the complaint, according to Kent State’s legal response to the initial suit. Title IX compliance dictates that faculty or staff members are required to report any and all complaints to a Title IX coordinator on Kent State’s campus.

The United States Department of Education has its hands full with these cases. A backlog of 329 Title IX suits, some dating back to 2012, wait to be investigated. Since 2011, only 62 cases have been resolved. At this rate, the department will need at least 30 more years to get through the remaining cases, as long as no more are filed.

In 2011, Russlynn Ali, then assistant secretary for civil rights of the Office of Civil Affairs within the U.S. Department of Higher Education, penned a letter imploring for the redefinition of Title IX to encompass sexual assault and harassment.

The letter’s opening takes a direct approach to the proposed changes:

“Education has long been recognized as the great equalizer in America. The U.S. Department of Education and its Office for Civil Rights (OCR) believe that providing all students with an educational environment free from discrimination is extremely important. The sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination and, in the case of sexual violence, is a crime.”

The changes were abrupt. Title IX would no longer be leashed to discrimination but include all forms of sexual harassment and violence.

Records obtained from Kent State show a dramatic difference in documentation following the publication of Ali’s letter and the broadening of Title IX’s reach.

Prior to 2011, records kept in Kent State’s Title IX office lacked any detail and only pertained to discrimination. Reported offenses were relegated to non-descript and esoteric numbers. Locations of discrimination were provided, but there was no documentation of the nature of the offense, no resolutions were recorded and names of the accused were oddly absent.

The abrupt changes in data keeping provide a look into sexual harassment cases on Kent State’s campus. While some seem frivolous — filing complaints after being asked out on a date — others showcase the depravity of some individuals. From dealing with cases of cyber stalking to forced anal penetration, Kent State’s Title IX officers have been diligent in their record keeping.

“The 2011 letter was a call to action,” said Bonita Prewitt, a gender, equity and compliance officer and Title IX coordinator at Kent State.

Prewitt’s name and initials are peppered throughout Title IX investigations. She helped oversee and investigate many cases as they went through the compliance efforts of the university.

While numbers don’t tell the whole story, the records kept by Kent State show a dramatic increase in Title IX complaints after the 2011 letter from Ali and redefining of the title.

From 2011-13 a total of 20 complaints were filed through the university. The years between 2014-16 total 147. The broadening of the definitions provided an influx of complaints to the university and began a push for more awareness and compliance. The information accompanying complaints changed drastically, as well.

Statements such as an August 2012 complaint: “Denied reasonable accommodation (pregnancy)” and a March 2011 complaint: “Alleges harassment from Assistant Manager of Parking Services” can be found in records prior to the changes. After the changes, complaints became much more egregious and sometimes difficult to read — the details can be graphic.

One November 2014 complaint claimed: “Student states she went to Respondent’s apartment. He performed oral sex and began intercourse. She said they should stop, but he only stopped after she began crying.” Another complaint from February 2015 recalls: “Student alleged that she allowed a drunken [REDACTED] player to stay at her house and that he later came to her room and anally penetrated her.”

The university offers many avenues of Title IX compliance, including the implementation of Affirmative Action Facilitators.

One facilitator, Amanda Leu, said the liaisons are trained yearly, including how to handle Title IX complaints.

“With a Title IX complaint, we connect (the complainant) with the Title IX office. There are such strict guidelines with reporting. We act as a support person; we must keep a neutral standing (during complaint interactions),” Leu said.

When a complaint is not put through the standard compliance procedures, the alleged victim of sexual discrimination, harassment or abuse can take the university to court. Kesterson’s lawsuit remains in the court system. It is set for a final pretrial conference in October 2018 and a jury trial beginning Dec. 3, 2018. The court did decide, however, to put the case through mediation in May of this year.

Linder resigned in August 2015, and the university agreed to “waive its option to collect early termination costs” and pay 25 percent of her base salary, according to her resignation letter.

Still, Kesterson and her lawyers continue to pursue legal action against Kent State.

Kesterson’s lawsuit brought another Title IX issue to light within Kent State’s athletic department.

An unnamed complainant filed a sexual harassment case against Senior Fiscal Manager Colin Miller in July 2016. The name of the complainant has been redacted, but she alleged Miller regularly harassed her by using his master key to enter her office and leaving unwelcome “risque notes and candy,” as well as other unwanted advances.

A compliance coordinator at Kent State’s Office of Compliance, Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action (EOAA), Katie Schilling, stated in the investigation’s report that the relationship between Miller and the complainant wasn’t mutual.

She goes on to claim Miller would “(position) himself behind female athletes to look at their bodies or butts. … It’s a running joke in Athletics that if you can’t find Mr. Miller, look in gymnastics and you’ll find him there.”

Kent State’s EOAA recommended Miller receive a 10-day unpaid suspension, an office relocation, a no-contact order, a revocation of his master key and a management referral to IMPACT Solutions for counseling. EOAA also warned that another violation be met with immediate termination.

Kent State provided information on proposed resolutions to Title IX complaints in a records request, but these resolutions are sometimes extremely vague. Some incidents had resolutions marked only as “SART.”

The SART, or Sexual Assault Response Team, is a service provided to the Kent State community.

Jennifer O’Connell, director of the Office of Sexual and Relationship Violence Support Services (SRVSS), said the SART is a committee of first responders at Kent State who help facilitate Title IX complaints and make sure complainants get the help they require; It is not a resolution.

“We’re making sure that the student is being offered and has access to the different accommodations — whether that’s academic, counseling, advocacy support, criminal process, university process,” O’Connell said. “As far as resolving actual Title IX cases, Title IX would get the complaint, if an actual complaint is filed, and they would do the investigation and move it forward in the process.”

A SRVSS office support service coordinator is the driving force behind all those different pieces, O’Connell said. SRVSS will help a student withdraw from a class or receive an excused absence, if needed.

“The student never really meets with the SART. The SART is just representatives from different groups — Kent State Police, the Student Conduct Office, Health Center — and we’re just there to say ‘OK, this student is struggling in this area, how best can we at the university serve that student,’” O’Connell said.

The resolutions in the Title IX records provided little to no details of investigations or sanctions based on the actions of the accused.

Some alleged offenders, however, are held accountable for their actions if Title IX coordinators and investigators do find them at fault.

In a heavily redacted April 2015 sexual harassment complaint filed, the only information provided about the incident is “video, FB posts.” Findings indicated “EOAA interviewed character witnesses for both complainant and respondent and reviewed videos provided by [REDACTED] campus security. [REDACTED] security did not have video of parking deck for Feb 4, 2015.”

The respondent (or accused offender) was found guilty of sexual harassment and referred to the Office of Student Conduct. The accused received a disciplinary action of a two-year suspension, a no contact order until May 2017 and counseling. The accused appealed and had his suspension reduced by half.

Other accused offenders voluntarily resigned, received “remedial training” or “disciplinary probation.” A large portion of cases went through the initial filing stages, but the complainant stopped responding to Title IX coordinators and the case was dropped. Resources are sent out to each complainant, including packets of information and links to outside services.

Prewitt said that after a complainant is contacted three times and still does not respond, the Title IX office will no longer reach out.

Kent State would not comment on individual Title IX cases, citing privacy and FERPA laws.

In an effort to further comply with federal standards for Title IX, Kent State is taking steps to make Title IX procedures known to students and faculty.

The Title IX office is planning to roll out a new program designed to educate incoming students about the process. During initial enrollment, incoming students must complete an online checklist. The checklist currently contains items such as immunization forms, transcript requests and the like. Prewitt said a Title IX worksheet will be added to the checklist.

Other items are on the office’s agenda. See It, State It, Stop It is an initiative aimed to provide Title IX workshops to the Kent State community. Workshops are set to be held monthly for faculty, staff and students.

In February, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rolled back previous advances made by the Obama administration. The new guidance diminishes Title IX coverage for LGBTQ students and gender-neutral restrooms and facilities, ceding oversight to individual states.

With a possible erosion of federal oversight for Title IX, it’s hard to say what efforts will be maintained. The Department of Higher Education is already bogged down with cases where universities are not in compliance with federal regulations or have neglected duties in reporting.

Kent State’s push for awareness may be curtailed by a growing movement to hand oversight to states. The slowly scaling back on regulation and diminishing definitions in Title IX seem to fly in the face of the efforts put forth by the university.

Karl Schneider is the senior editor, contact him at [email protected].