Gender disparity apparent among KSU faculty

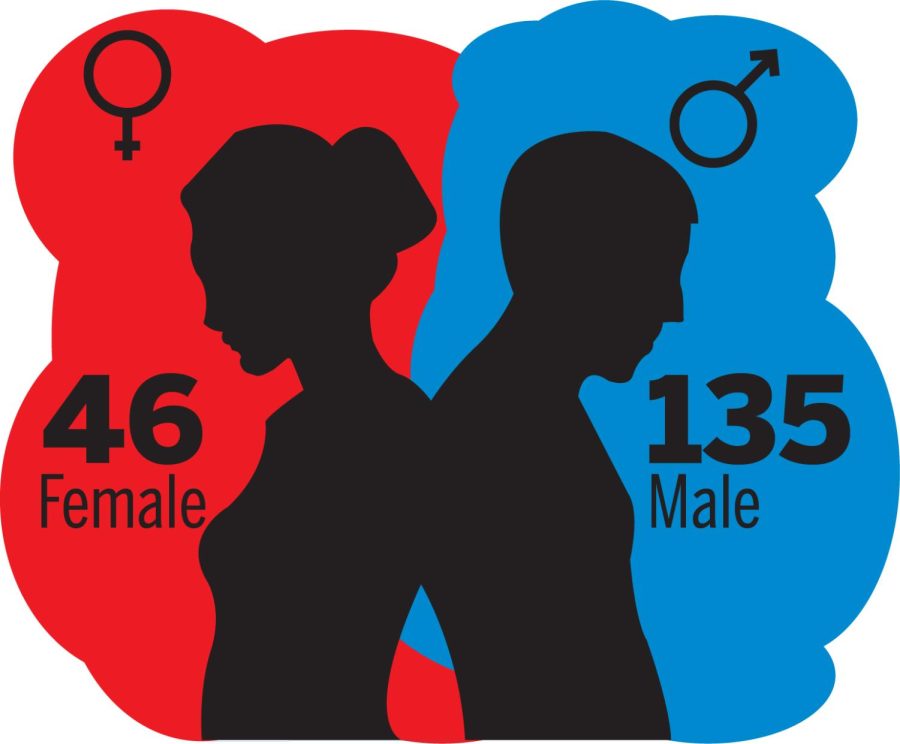

Women make up only 25 percent of the full professors on campus, according to information provided by Kent State University’s Chapter of American Association of University Professors.

April 4, 2017

Dianne Kerr, a health education professor at Kent State for 27 years, said she isn’t surprised to learn that only 25 percent of full professors at the university are female. The disparity is one baked into the culture of academia; it’s as a much a product of the system as individual circumstance.

“I did not apply to be a full professor until 2015,” Kerr said. “I bring that up because I think that I’m typical of a lot of women faculty who feel they have to have every qualification to get promoted, whereas male faculty will put their file in early and say, ‘If I get turned down, so what?’”

There are only 46 female full professors at Kent State compared to 135 of their male counterparts, according to information provided by the Kent State Chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP-KSU). This data only represents full professors at the university, which is the highest academic designation a professor can attain.

Kerr said it’s a combination of cultural and systemic forces that make women feel unqualified compared to men. She said she has seen women leave the university after being turned down for a promotion.

“There is still a bit of, I think, the ‘good old boys’ network in most institutions,” Kerr said. “It just seems that men get promoted more. I think it’s also a function of women not putting up their materials earlier.”

The disparity at Kent State is more striking when considering the makeup of the university.

According to the recent Kent State Campus Climate Assessment Project, more than 19,000 — approximately 60 percent — of students at the university are female.

“It’s incumbent on these universities to become more representative — to look more like America looks,” Navjotika Kumar said.

Kumar was an art history professor at Kent State until her contentious and racially-tinged tenure case resulted in her leaving the university.

Kumar was denied tenure by Todd Diacon, senior vice president for Academic Affairs and provost, after receiving nearly unanimous positive votes from her colleagues. She alleged discrimination and the AAUP took the case to arbitration. It remains unsettled.

“It’s very weighted by race. It’s hard for faculty of color to basically enter the halls of academia,” Kumar said. “(Universities) have the responsibility to their students, who are increasingly diverse … They have to have faculty that cater to the needs of those students — who those students can identify with as models.”

After she left the university, her job was given to a white male, Kumar said. While her situation is certainly circumstantial, within it are trends that reflect a broader disparity in academia.

A study by the Chronicle of Higher Education shows disparity between genders when considering representation, pay and professor rank. The study, published in 2014, says “male full professors make up 26 percent of total full-time faculty, while female professors are only 8.4 percent.”

This disparity holds at the associate and assistant levels, although at smaller gaps. Women actually outnumber men at the lecturer and instructor levels, something Linda Hoeptner-Poling, an associate art professor, said speaks to part-time faculty being largely female.

“There are more non-tenure track and adjunct female professors than there are male,” she said. “That is in connection to that caregiving. They cannot do this grueling, full-time tenure track life because of caregiving responsibilities.”

Although data specific to Kent State couldn’t be obtained to substantiate the adjunct demographics, Hoeptner-Poling said academic literature suggests this is a nationwide trend.

Hoeptner-Poling delayed her attempts for promotion for 15 years after she was hired at Kent State as an evening adjunct while teaching grade school during the day. Her promotion was put on hold because she had to shoulder the caregiving duties of her two young children and dying parents.

“I knew male faculty in a similar situation — with young children, dying parents — their wife did it,” Hoeptner-Poling said. “They were able to focus on their research because they knew their wife would go take care of everything.”

For his part, Diacon is trying to be intentional about increasing gender diversity among the faculty at Kent State.

“I’ve always said that at a minimum, (a university) should reflect the diversity of the state,” he said.

Right now, Diacon said Kent State falls short of that goal, but that hasn’t deterred the university from working to develop female leadership.

“We started sending our female faculty — two or three a year — to the (Higher Education Resource Services ) Institute,” Diacon said. “This is a very intensive three-week workshop that’s held in the summer to develop leadership amongst female faculty.”

The institute claims to have trained nearly 5,000 female faculty and staff members since 1976 to enhance and enrich their leadership capabilities. Its website describes the institute’s mission as “advancing women leaders and advocating gender equity.”

The provost isn’t the only campus leader working to increase female representation on campus; Kerr said she sees solutions on the horizon and is actively working in pursuit of them. She suggests universities do more training of doctoral students to negotiate with administration and ultimately demand more in terms of wage and status.

Kerr has also helped lead faculty workshops to help female professors navigate the promotion process, and she said this effort needs to increase for those seeking full professor status.

Despite the hurdles women in higher education must navigate as they ascend in their careers, Kerr said she’ll remain an active advocate and willing participant in the fight for equity.

Andrew Keiper is a senior reporter, contact him at [email protected].