Losing Dylan: A mother’s story

May 4, 2016

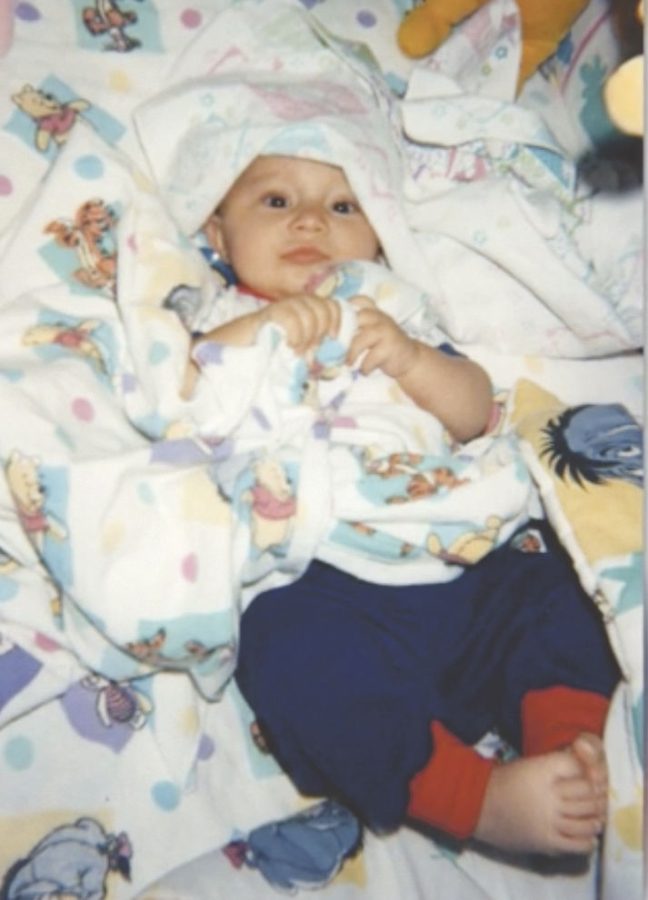

Editor’s Note: Dylan Stone, a Kent State business major, lost his life to heroin. Dylan’s mother, Juli, agreed to tell the story of her son’s addiction in her own words.

My son died alone after a 6-month battle with heroin.

It was March 11 and my husband, Robert, and I were at an appointment when he tried calling us. He left a message, but wouldn’t pick up when we tried calling him back.

Instantly, I was sick because I knew. He didn’t answer. We flew home and I knew.

On his voicemail, all we could hear was him rustling around. We think we were listening to his last breath.

Our world is destroyed forever.

- When Dylan was in fifth grade, his travel baseball team won the state title because of him. His teammate hit a single and they put Dylan in to pinch-run. Before you knew it, he had stolen from first to third base. It was a tie game, with two outs—his coach told him, ‘Don’t steal.’ Well, he stole anyway.

They won.

While his teammates were carrying him on their shoulders, the coach was screaming, ‘I told you not to steal!’

That was always kind of him—he was always going to push it.

Everything came easy for Dylan: teachers loved him, he was good at sports, girls liked him, he had plenty of friends—he had it all.

He was the oldest of our kids. I used to always think, when he was younger, how happy I was that he was the oldest, because he was very responsible. I was on bedrest my entire pregnancy with my 13-year-old daughter Audrey. Dylan was only in kindergarten, but he did the laundry, washed the floors and waited on me hand-and-foot. Dylan treated our one son like his own baby—he didn’t walk until he was 16-months-old because Dylan carried him all the time.

I was always so thankful for him.

Dylan did everything early. He stood up and took his first steps at eight-and-a-half-months old. I remember, when he was in grade school, he broke his arm playing football and the doctors had to put a hard splint on his arm. One day, he climbed up a tree and fell and broke his cast. I had to explain to the doctors how my son, with a broken arm, had broken his cast. But, he was always so adventurous; he always wanted to have fun.

He just always was very funny. He could make me laugh no matter what. If I was in a good mood he knew. If I was in a bad mood he knew.

For the last year-and-a-half of his life, Dylan took care of my 101-year-old grandpa—cooking his dinners and doing laundry. They’d have outings for ice cream and hardware store trips—Dylan never missed a day no matter what because family was very important to him.

He loved old cars. He used to attend car shows with my mom and stepdad; I used to joke that they loved him more than they loved me, but it’s true. They really did.

Dylan always excelled at sports, too. He played football from age six all the way through high school. He was always pretty shy, but coaches said he was a whole different person on the field.

- His substance abuse issues first started in high school. There were upperclassmen using drugs: smoking weed and snorting Adderall and cocaine. Dylan was the kind of kid who wouldn’t smoke cigarettes; he’d always say they were bad for his body. But, to him, smoking marijuana was OK. We fought about it all the time and did everything we could to stop it. In the end, there’s only so much you can do.

The biggest reason why he turned to heroin was he couldn’t sleep—he never could, not even as a baby. He was always concerned about other people being upset and, honestly, he probably cared too much about what other people thought. I think that’s why he couldn’t sleep; his mind would race at night.

When his best friend, Andrew Moncheck, died at the hands of a drunk driver, things only got worse.

(Editor’s Note: On July 12, 2014, Stow-native Andrew Moncheck, 18, was struck and killed by David Brown on Interstate 77 in Bath Township. It was Brown’s fourth drunk driving-related arrest and ninth car crash since 1996.)

Dylan was supposed to be with Andrew, but Dylan went on a senior trip to Myrtle Beach. I had to make the call and tell him he needed to come home. It rocked his world.

To make matters worse my grandmother passed away shortly after. They put him on Benzodiazepines, Valium, Xanax, Ativan and Klonopin—you name it he had it prescribed. But he couldn’t sleep. The physician then stopped prescribing them all.

Last summer, an upperclassman told him, ‘Heroin will make you sleep even better.’

That’s when his addiction began.

I first learned he was using heroin in August 2015. He was sick and wanted to quit it all; he came to us and asked if we could take him to rehab. He didn’t use very long—six months at most. He wasn’t someone who was using for years.

He started by snorting heroin, but then began injecting it—someone had told him that you can buy a box of 100 insulin syringes for $8 at Walmart.

I would never, in a million years, have thought he would inject. He would never share a needle, but once he knew he could get his own packages, things changed.

My son was ashamed. He didn’t want his brothers and sister to know he was going to detox—he asked us to tell them he was camping. We kept it quiet; none of them really knew.

He lasted three days at a detox facility in Akron. I remember thinking, “this is the kid who inspects spoons at home to see if they’re clean—this is not going to fly well.” He was always neat, right up until the very end. He told me, ‘The whole time I was there I wanted to use’ because it was not a good experience.

We took his car away and were driving him back and forth to school at Kent just to limit his ability to go get heroin. But that didn’t prevent him—of course. Friends would drive him to Akron to go get it because they wanted to do it too.

He tried to stop many times on his own, and I know he was cursing the person who introduced him to it and wishing they would die because he was so sick. He thought he was stronger and smarter and that this wouldn’t be him; he could take it and quit whenever he wanted. There are so many misconceptions about using.

In January, he overdosed for the first time. My husband (an Intensive Care Unit registered nurse) found him and had to do CPR on him. I was getting my nails done at the spa on Graham Road. He was awake in the emergency room for all of two hours and then the doctors sent him home.

His brothers and sister didn’t know about his addiction until he overdosed, but they knew then.

We took him out of classes and brought him home. Later that week, he left the house on foot and used again. I went to check on him and, although he was breathing, he was completely out of it. This time, my husband just loaded him up in the car and took him back to Akron General Medical Center.

By the time I got there—I had to wait for someone to come pick up my daughter—they were already signing the discharge papers. There was nothing; no toxicity screens or psychological consultations, even though I requested one. It was basically, ‘Oh, here you go.’

They gave us a prescription for an injectable can of Narcan (Naloxone). The next day, he was very sick and by Sunday, he was begging us to give him money so he could go use just so he could stop the cravings, which we wouldn’t do. My husband was literally restraining him and his brother had to tackle him in the snow.

We knew he needed help.

Monday, Glenbeigh (an alcohol and drug treatment center in Rock Creek, Ohio) called and said they had a bed. We saw him on Saturday after his first week—he was so sick they extended his detox. Finally, the next week, you could see he was starting to get better.

Our first visit, we talked the entire time we were with him—he told me everything—most of which I already knew by then.

I knew he was getting better, because he would give me a whole list of food requests: Emidio’s pepperoni pizza with extra bacon and a cannoli, or my mom’s cupcakes—all of his favorites.

We planned on getting him into IBH (An addiction and recovery center) in Akron because they have a 90-day residential treatment program—longer than Glenbeigh’s typical 30-day stay—and he needed more time. Your brain simply doesn’t heal that fast. We asked for special permission to take Dylan out of treatment at Glenbeigh early, and on Feb. 15 we picked him up to get him assessed.

Robert and I waited for Dylan in the parking lot for six hours. I asked him if he was on the waiting list when he came out and he replied, “Mom, they said I can’t go to IBH.”

I was fuming; I didn’t know you needed to have Medicaid to receive treatment. I couldn’t understand why my son couldn’t go because he had private insurance, two parents, a home and a driver’s license. When he first overdosed, we asked one facility if we could bring him in. They told us, “bring him in, in a week.”

I didn’t think he would make it that long; I thought he’d be dead in a week.

When someone is trying to get services, they shouldn’t be denied because they don’t have Medicaid. It’s a messed up system. He should have had more time. He should have had more time to heal.

People think, ‘Oh, they just need to ask for help.’

Well, bullshit. That’s not the case.

On March 1, he came home. We were unsure what to do. My husband and I set it up so that one of us was always home with him and he went to a meeting once a day, sometimes more. We drove him every time.

He began IOP (Intensive Outpatient Program) treatment. Dylan told me he didn’t mind the them, which surprised me because he wasn’t always so keen on group meetings with people he didn’t know because he was shy by nature.

Dylan liked going to the Big Book meetings (A form of meetings focused on specific readings) because it was a little more intellectual and you talk about it versus the meetings where he said people ‘bitch about their lives and feel sorry for themselves.’

He sent me a text, I said: “How was IOP and what time is your meeting today?”

“Good,” he replied. “The counselor calls me Princess.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Because I look so young and innocent and good-looking,” he responded. “It’s kind of embarrassing, but whatever.”

Wednesday, March 9 was the first day he was alone at home. I was a nervous wreck. I beat myself up about going back to work.

Thursday, our friend drove him to meetings. He’s a music teacher and was going to teach him guitar lessons because Dylan was bored at home. Dylan liked to be busy; when he had a lot of things to do he was at his best. So, him sitting at home wasn’t really good for him.

Thursday night, he went to a meeting and he talked to a couple of his friends he made at Glenbeigh.

Now, I know that his friends from Glenbeigh had used a couple of different times. From what they tell me, Dylan was the one on them saying, “Don’t use or I’m going to kick your ass.”

They felt like he was the strongest one of them.

He hated heroin. Hated it.

- I knew something was up Thursday night—he was up late. He was back on medication for sleep and had been going to bed. But, that night he wouldn’t go to bed, he kept talking about guitar lessons or transferring to the University of Florida. His grades weren’t great. It’s amazing he passed anything his first semester to be quite honest—he was high the majority of the time.

It was one of those situations where you’re still half asleep and don’t snap right into things. He just said, “Nevermind Mom, I’ll talk to you about it later.”

That’s the last time I ever talked to him.

I’ll never understand what happened that Friday, ever. All I know is it’s that strong of a craving. People have that negative opinion about using, but 75 percent of people are addicted after one try.

I know this: If this could happen to my son, it could happen to anyone.

- He had been home 11 days—clean for 48 days—and he had snorted it. There wasn’t even that much, we haven’t gotten his toxicity screens yet, but suspect there was fentanyl in it.

Editor’s Note: Fentanyl, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, is a powerful synthetic opiate analgesic similar to but more potent than morphine. When combined with other abused substances, fentanyl can markedly enhance their potency and danger.

As angry as I am about the person who brought it to him, I’m more upset about the lack of services.

My husband and I both constantly see him lying on the floor. If I sleep for three hours, it’s a good night. I can’t go in his room.

I am in denial. I either think he’s still in Glenbeigh or I can’t function. You know, you try very hard to keep it together, especially for the other kids. We don’t want to see them so upset.

I literally think about him every second of every day. You rehash and rehash, ‘What could you have done differently?’ I feel angry at him, sad for him, and you feel like you failed him as a mother. People always said I needed to cut the cord with him, I have four kids, but it was just different with him. We just had that connection and now it’s gone. I love my other kids but no one can make me laugh like he could. And that sucks.

We were open and honest with each other and so I know kids his age who are using. I’ve reached out to a couple of them. I’ve reached out to parents, too. Some are in disbelief. People don’t want to believe it’s a big issue, but it is. And it’s a big problem in Kent.

Editor’s Note: The Kent City Police Department said they typically receive eight to 10 heroin-related calls per month. Wayne Enders, the coroner’s office administrator, said Portage County ranks at the fifteenth largest county in Ohio.

- I want people to know that if someone is using they need to run toward them not away from. That’s what they need. I want to tell people to educate themselves; don’t be ignorant about this. He had a supportive family with two parents, siblings and grandparents. He had all the right things. He wasn’t from a broken home, we weren’t arrested or criminals. He had it all.

Our world is forever destroyed. He should have been going to school, planning his future, dating, having kids—all these things he’s never going to get to do. We feel cheated.

Dylan didn’t fail. I’m proud of my son, I know who he was and how he was with my family. I’ve had people come up and tell me things he did for them—he would do anything for anybody. But this is an addiction, and once you start, good luck getting off of it.

- A friend made me a charm necklace to remember him: It has a ‘D’, a heart that says ‘son,’ an angel wing, a football, an old car, a dolphin and a sand dollar. Every beach vacation our family took, he was a dolphin because he could hold his breath forever and he’d always collect so many sand dollars, his boogie board was covered.

And, there’s the legend of the sand dollar.

Now break the center open/

And here you will release/

The five white doves awaiting/

To spread goodwill and peace./

This simple little symbol,/

Christ left for you and me./

To help to spread His Message/

Through all eternity./

Without him, our world is forever destroyed.