Opinion: My experience as a first generation college student

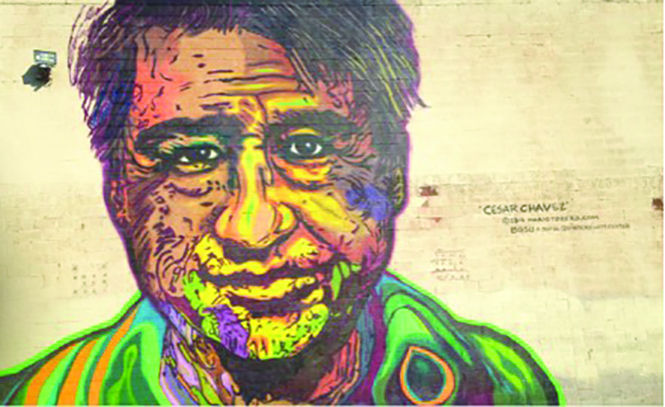

A César Chávez mural on Broadway Street in Toledo, Ohio painted by Bowling Green State University students.

April 26, 2015

Local Background

Northwest Ohio boasts a large Mexican and Mexican-American or Chicano population. This is due largely to the availability of jobs during the early part of the 20th century. Toledo, Ohio, is home to the headquarters of the famed Farm Labor Organizing Committee established in 1967 to advocate for the rights of laborers working in the local fields. It was established in the same spirit of the famous farm labor organizer, César Chávez who established the National Farm Workers Association just five years earlier in 1962.

Family History

My father attended a trade school and became a certified mechanic while my mother made the conscious decision to quit high school in order to take care of her grandmother and ensure that the household was maintained while both her parents worked during the day. Neither of her parents graduated high school.

My father attended a trade school and became a certified mechanic while my mother made the conscious decision to quit high school in order to take care of her grandmother and ensure that the household was maintained while both her parents worked during the day. Neither of her parents graduated high school.

“A house with a lot of people demands a lot of attention. You know, someone has to always take the trash out, someone always has to clean the toilet,” my mother said to me.

Her parents both came from migrant families. It was not unusual during the first half of the 20th century for many people to travel across the United States looking for work. Both of my grandparents’ families moved throughout the country looking for fieldwork and hoping to find a permanent place to settle into.

My father’s parents also worked in the fields.

His mother was born in México in 1943 and later became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1969, but she started working in the fields at the age of 9. Her father was also born in México but obtained papers that listed him as a bracero which originates from the word, brazo, or arm in Spanish. Bracero referred to “one who works with their arms.” This title on an official government document allowed for many non-U.S. citizens to enter the country as laborers.

We were people who traveled from job to job as migrants,” my grandmother explained.

Access to education as a child, too, was sporadic as my grandmother went to the local school wherever her family happen to be working or sometimes not at all. By ninth grade, her parents took her out of school permanently informing her that she didn’t need an education to have a baby.

My grandfather and my grandmother married when she was 17 and he was 30. Theirs was a marriage of pragmatism. In those days, my grandma tells me, you didn’t have any choices as a woman. You married who your parents thought would be able to provide for you and your future children

They arranged for us to get married because they worked at GM and they could provide for us and get us out of poverty,” my grandma tells me.

Back then they asked for the hand of the daughter. Whether you were in love or not, you’re getting married,” she said.

My grandparents divorced in 1990, and my grandmother remarried Justino Aguilar in 1994, who is originally from México. She helped Aguilar study and learn all the necessary information to become a naturalized U.S. citizen.

My grandmother tells me that had she been given the opportunity to go to school; she would have loved to been able to study to become a lawyer.

Despite all the obstacles as a child, my grandmother has never given up on education. A few years ago, I helped her with her writing and sentence structure as she studied to obtain her high school diploma, and in 2007 she was awarded this long overdue credential.

When I began inquiring about primary documents from her and her family’s past, she brought out this large zipped file full of government issued documents from the United States and México.

It felt absolutely fitting for her to be so organized and thorough given the fact that she wanted to study law growing up.

Leaving Home to Go to School

My earliest interaction with the education system is also my earliest interaction with institutionalized prejudice. A preschool teacher told my mother during a parent teacher conference not to teach Spanish at home citing the belief that it would confuse my younger brother and I.

My mother, having complete trust in the education system, took the teacher’s advice.

I was once told later, in a rather accusatory tone, by a classmate my senior year of high school that the only reason I had been admitted to any university was due to affirmative action.

I found after talking to Ryan Kreaps, a senior psychology major, that the experience of a rural, small-town way of thinking was still alive and well. Kreaps said he comes from a very bigoted area.

“You hear the n-word,” Kreaps said.

Seeing people drive around with a confederate flag, Kreaps said, makes him cringe. Kreaps said he definitely experienced culture shock when coming to college.

Kreaps, like me, is what many folks in academia would call a first-generation college student. This simply means that we are the first in our generation to attend a four-year institution of higher learning.

I have already received my bachelor’s degree and am currently within reach of my master’s degree. This achievement, however, is not without its own bittersweet irony. While I may have fulfilled a great hope for my family, I have a six-figure debt to worry about after I walk across the stage to accept my diploma.

Brandon Morton, a junior philosophy major, told me that the debt situation for a lot of first-generation college students is definitely a “chair of privilege.”

Students whose parents were better off financially from the beginning, he said, are able to better provide for their students when college comes. He also spoke to the disconnect that occurs between peers when some students are able to drive around in brand new cars and take Spring Break trips that they may not have had to pay for while other students work to pay their bills while they are also going to school full-time and cannot afford the same experiences as their peers.

Rachel Mass, a sophomore English major, also spoke to this disconnect between peers. Mass shared a story in which she was telling a friend about a $40 sweatshirt she wanted to buy but couldn’t afford because she didn’t have enough money.

Her friend told her that she should just go ahead and buy it; however, Mass wasn’t just saying she didn’t have the money as an exaggeration but literally didn’t have the funds.

Morton talked about the overall confusion that can occur for a first-generation college student because he or she doesn’t have a team of people to ask, “How did you get through this part of college?”

He specifically was referring to the balance of the social, academic, and work demands of being a college student.

Morton and Mass are also first-generation college students like Kreaps and I. All three students agreed that a college degree isn’t necessarily the key to success.

The key to success, Mass said, is circumstance. She elaborated by explaining that for a lot of folks, it is a bit of luck.

“Sometimes opportunities come and sometimes they don’t,” she said.

Kreaps said that for him, an ideal situation would make education “free and accessible to those who want it.”

“It should be a public good,” Kreaps said. “For me personally, it’s my key to success because I love learning now.”

Kreaps also said he lacks the skills to fix a car but admires those who have these kinds of skills that he does not posses. In his ideal world, society would value both paths: the college path and the labor path.

My younger brothers, Tom Paniagua III and Isaiah Paniagua, work as a press operator in a factory and as an employee for the village of Deshler, Ohio respectively.

“I think we all knew you would be the one to go to college and continue it,” Tom said. “You were always the smartest and brightest.”

Both my brothers said that they felt pressure to follow in my footsteps. Tom attempted a semester but due to health related complications, found himself unable to maintain the demand and decided it wasn’t for him.

Isaiah said that he definitely felt pressure from mom and dad to go to college because he knew mom and dad wanted him to have the best possible life.

“I thought that maybe I would need a college education to make it, and I realized later down the road that maybe that’s not what I needed to do and I’m happy just working the job I am now,” he said.

Tom has a small amount of student loan debt that can easily be paid back in the next few years while Isaiah is debt free.

The Future of Education

According to the Institute for College Access and Success, in 2013, 76 percent of the student population at Kent State was in debt with the average amount lingering at $31,543.

With the rate of tuition increasing and the state funding for public universities decreasing, the business model of education is steadily inching toward an unsustainable end.

Yet, advancement project after advancement project at state universities continues to feed into a competitive race to have the “prettiest” campuses and amenities that even the Huffington Post can’t help but call these places Country Club Colleges.

Meanwhile, adjunct faculty is paid exploitative wages that result in seeking out public assistance. Administrators continue to micro-manage all aspects of the university at the cost of full-time, tenured faculty.

All of these facts plague my thoughts, especially as someone who would like to teach in the collegiate setting some day. Today, as a student, I know that I will try to instill in my students, some day, the same spirit to push back at an education system that is, in my opinion, fundamentally flawed.

Contact Amanda Paniagua at [email protected].