College life through the eyes of students with learning disabilities

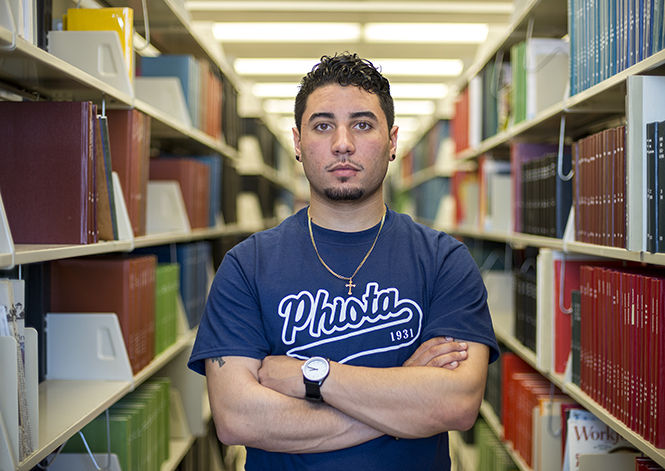

Senior technology major John Camargo, said his learning disability has made him unique and helped to improve his work ethic.

April 29, 2015

A teacher in high school once laughed at Hilary Mendel, a graduate student and teaching assistant in the College of Nursing, and told her to pursue a less competitive college major.

She said Mendel wouldn’t get into the nursing school of her choice due to her learning disability.

Ten years later, the teacher’s words still stand out in Mendel’s mind.

“I wish I could send her an email to let her know that I got in the first time I applied,” said Mendel, who has reading, writing and auditory processing impairments. “I selected nursing education for my master’s in order to help students with their own struggles. I openly tell my students that if they want to become nurses bad enough, they can and will overcome any challenge.”

Students with learning disabilities often experience the same type of discouragement from their peers and teachers in high school, which deters them from seeking help in college or other postsecondary settings, said Amy Quillin, director of Student Accessibility Services (SAS).

“We try to tell students that this is a big place, and we as a university want it to feel really small and intimate,” Quillin said.

Only 17 percent of students with learning disabilities received accommodations in postsecondary education, but 94 percent of students reported receiving accommodations in high school, according to The State of Learning Disabilities Facts, Trends and Emerging Issues, a 2014 publication of the National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD).

Fifty-five percent of students with learning disabilities also said they planned on receiving accommodations in postsecondary education. However, the publication said students contacted disability resources only 26 percent of the time.

SAS at Kent State works with students who have a variety of disabilities. The largest category of students registered with SAS is learning disabilities. Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) make up the second largest category, Quillin said.

Quillin said SAS typically considers learning disabilities based upon impairments in reading, writing, math or auditory processing. Some postsecondary institutions combine the categories of learning disabilities and ADHD, but Kent State accommodates those groups separately, she said.

Students with learning disabilities must self-identify in order to receive disability accommodations at Kent State. Schools are generally responsible for finding the students with learning disabilities, assessing their disability and providing appropriate support in kindergarten through grade 12, Quillin said.

“In postsecondary settings, it’s essentially the student’s responsibility to self-identify, so we don’t necessarily go looking for students with disabilities,” she said. “Now, we certainly want to be available, obviously accessible. We want to be visible, but we don’t necessarily go looking for students.”

Quillin said she often sees students who do not use the disability resources available to them during their first semester at Kent State. Many students want to see if they can successfully complete assignments on their own. Typically, these students seek SAS support during the beginning of their second semester, she said.

“Some of the reasons that we hear that they don’t want to use our services are because there was sometimes a stigma attached to having a learning disability or having to take their test somewhere else,” Quillin said.

According to the 2012 Survey of Public Perceptions of Learning Disabilities by NCLD, 43 percent of U.S. respondents incorrectly believe learning disabilities have a direct correlation with IQ.

“I wish there was more education about it, like people would understand better,” said Nicholas Carpenter, freshman computer science major with dyslexia, an impairment of recognizing and processing words. “Some people see us as dumb sometimes.”

Students with learning disabilities not only feel misunderstood by their peers but often by their professors, as well. Mendel said she found that many postsecondary professors are not properly educated about how to work with students who have learning disabilities.

John Camargo, senior technology major with reading and writing impairments, said graduate assistant instructors in particular need more training on how to teach students with learning impairments.

“I think even amongst professors, they don’t really grasp that concept,” Mendel said. “Someone with a learning disability is not necessarily stupid or trying to get away with something. We really don’t get one area, and we really need help with this one area, but in this other area, we’re going to excel.”

Camargo and Mendel, like many other students with learning disabilities, said they feel their disabilities do not define them. In many ways, Camargo and Mendel believe their disabilities have allowed them to achieve a stronger work ethic and sense of uniqueness.

For students with learning disabilities, writing papers and completing other projects can take weeks to prepare. However, students without learning disabilities may be able to complete the same assignments in one day. Time management can be particularly challenging for students with learning disabilities, said Micaela Moreno, freshman fashion merchandising major with ADHD and a reading impairment.

College allows students with learning disabilities to choose a career path that shines light on their academic strengths and excel in more hands-on activities, Mendel said.

“A lot of people kind of look down on me saying that, oh you have a disability, so that means you must be slow in some way, and it’s like no, it’s just the fact that I don’t learn the way you learn,” Camargo said. “I learn in a different aspect, and I can learn quicker in that aspect than you can just reading a notebook. For me, it helped me become unique.”

Contact Victoria Manenti at [email protected].