The Risman Wind Tunnel: A tale of wind, trees and people

March 11, 2015

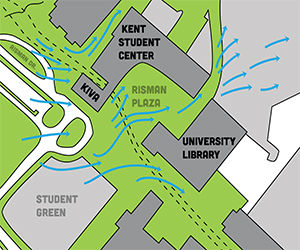

At Kent State, winds blow from the front of campus and whip down the Esplanade toward the Student Center and the University Library. The winds traverse over the hills and blow gently through the trees scattered across campus. Once they reach Risman Plaza, however, those gently flowing winds become cramped and congested.

Suddenly the winds hit the hard angles of the Student Center and the library arch, said Charles Frederick, Kent’s interim director of graduate landscape architecture program.

“The northeastern part of campus isn’t so windy because of the hill and the vegetation,” Frederick said. “Once the wind starts to travel down the pedestrian path, it’s free to pick up speed.”

Wind flowing on an open path isn’t very noticeable, but as soon as it’s constricted, wind speeds can really pick up. Think of a construction zone on the highway.

“People can pile up for miles, and they just creep along because you’ve got two or three lanes merged into one,” said Jonathan Secaur, an assistant professor of physics. “As soon as you get to that point and there is no one in front of you anymore, you zip right along again.”

This same concept works with wind, he said.

“(People) think about air as like being nothing, but it really is,” Secaur said. “It’s surprising how much there is to air. All those molecules are a lot like a zillion little cars trying to get through a passageway. They might move at some reasonable speed when they’re out in the open but when they get to a constriction, they just have to speed up to get through.”

The path that the wind takes down the Esplanade doesn’t constrict the flow until it blows past the Student Center and enters the main plaza outside the library. Not only is the wind picking up extra speed there, but it is also encountering the corners of the buildings that line the courtyard.

“Once, I was walking through the plaza and it was really windy,” said Christina Lamorgese, a sophomore pre-dentistry biology major. “I was headed towards the science wing and the wind literally pushed me over. It was pretty embarrassing.”

These winds can cause some trouble for students as they walk through Risman Plaza.

“I’ve seen people who have to lean forward in order to keep going,” said Courtney Kennell, a sophomore stage management major. “The wind is so bad it tends to burn my skin.”

The Arizona connection

One explanation for the wind tunnel effect in Risman Plaza might be found in the dryness of Arizona. Some students around campus believe an architect from Arizona designed the area and used principles of design that enable extra wind flow.

“Since the ‘90s, I’ve heard that the redesign of the Student Center was done by an architect who designed a campus in a warm climate,” said Joe Fischer, a senior zoology major. “But the winds were worse before they redid the plaza.”

Fischer is not alone in his belief in this idea.

“I’ve always heard about the Arizona campus (architect), but I also think it has to do with lake effect winds from Lake Erie and all the hills on campus,” said Patrick Snead, a sophomore political science major.

The Arizona architect theory may make sense for a warm climate. Flowing wind helps to relieve us from the oppressive heat of a hot climate, but these explanations are just rumors, and rumors carry little weight.

“That is an urban myth,” said Michael Bruder, executive director of facility planning and design, about the Arizona architect.

Architects based in Ohio designed the Risman Plaza and the surrounding buildings.

Stickle Associates, Architects and Engineers of Cleveland, Ohio designed the library and Richards, Bauer, & Moorhead, Architects and Engineers of Toledo, Ohio designed the Student Center and original plaza, Architecture Database Coordinator Cheryl Smith said.

With the Arizona myth debunked, students have other ideas as to why the winds get so bad on campus. Everything from the height of the library to the contours of the local topography is used to try and explain the formation of the winds.

“It’s probably because of all the hills,” said Doug Stewart, a freshman sociology major. “I think the elevation and the hilly area has a lot to do with the winds.”

Claire Thiele, a junior zoology major, and Dean DePerro, a junior pre-medical biology major both think that the height of the buildings surrounding the plaza cause the winds.

“I was thinking how (the winds) might be caused by the buildings being so stark, tall and straight,” DePerro said.

Creating chaos

One fifth-year senior, Anthony Zawahri, an integrated health studies major, likened the winds to a literary adventure’s landscape.

“The journey to class was more treacherous than Frodo Baggins’ journey to Mordor,” Zawahri said, referencing “The Lord of the Rings.”

The sharp corners of the Student Center and other buildings surrounding Risman Plaza force the wind into unstable patterns, creating vortices and turbulence.

“If you’re in a swirl like that — a vortex — then suddenly it’s blowing the other direction, it seems like it’s windier than normal because you’re aware of that sudden change in the wind,” Secaur said. “We feel changes in motion rather than motion itself.”

The physics professor compares these changes in wind direction to the difference between a roller coaster and a train: Even moving at the same speed, a roller coaster has twists and turns that create an exhilarating ride, whereas a train typically moves on a straight path and passengers rarely notice the motion.

The science behind fluid motion can be challenging to nail down, Secaur said. To monitor the variable wind speeds and directions near Risman Plaza would take a great commitment of time and resources, something almost impossible to do.

“You would probably need 100 people with anemometers standing in the area,” he said. “And you would have to take note of their readings, somehow trying to hear them over the winds and the distance.”

An anemometer is a common tool used to measure wind speed. The device uses a propeller fitted with three or four cup-like objects positioned to catch the wind and spin as the wind blows.

The hot and cold of motion

The combination of speed and the variability of the wind’s direction make the wind more noticeable to students venturing through the area, but the temperatures can play a role as well.

“It happens in the winter and the cold weather makes us feel more uncomfortable,” Frederick said. “It’s not like a nice breeze on a hot summer day. Students are already bundled up against the cold so they are more aware of the wind in the winter.”

It’s precisely this colder weather that creates the winds in the first place.

“We have wind in general because of changes in pressure and mostly because of changes in temperature,” Secaur said.

The changes in atmospheric temperature create a basic physics principle known as a heat engine.

“A heat engine is any device that turns heat into work (into motion),” Secaur said. “The atmosphere is a giant heat engine because it’s hotter in some places than others. So when a cold front comes in — when you have warm air in place and cold air starts to mix with it — that’s when you get the winds because you’ve got energy required to make the wind move.”

Fighting nature with nature

Kent’s campus was originally built by working off the hill near the northwest portion of campus at the corner of South Lincoln Street and East Main Street. As the university expanded, buildings were constructed along the pedestrian corridor. Areas with more vegetation are likely to experience less winds.

“Microclimates, like the shrubs and trees, can create protection from the winds,” Frederick said.

These microclimates can help protect small areas of campus from these wild winds. The vegetation acts like a filter that the free-flowing wind can’t overtake.

Conifers are good for both the summer and winter, said Thomas Schmidlin, a geology professor in the geography department.

“Conifers keep their needles all year long,” he said. “They disrupt the wind as the wind goes over (the trees). They slow it down and it becomes turbulent.”

As an example, a 30-foot tree will have about a 300-foot area that is protected from the wind, Schmidlin said.

“Farmers in the Great Plains will plant rows of trees on the north and west sides of their fields to really slow the wind down,” Schmidlin said.

The Esplanade sports one of these microclimates between the Art Building and the Business Administration Building. If it’s a windy day and someone stops to rest in that area, her or she will notice that the winds aren’t as extreme because of the vegetation surrounding the area.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to keep a tree growing in a windy spot.

“They can dry out and they’re usually planted in some type of artificial turf,” Schmidlin said. “The wind also affects the trees, too.”

Contact Karl Schneider at [email protected].