ISIS beheadings spark fear in young journalists

September 10, 2014

A global conversation about violence against journalists began when footage of an American journalist’s execution at the hands of the terrorist group Islamic State of Iraq and Syria surfaced on Aug. 19.

The video of journalist James Foley’s beheading was released along with warning for President Obama: Failure to end American military involvement in Iraq would result in the death of another American.

On Sept. 2, ISIS released footage of a second American journalist’s beheading, Time contributor Steven Sotloff.

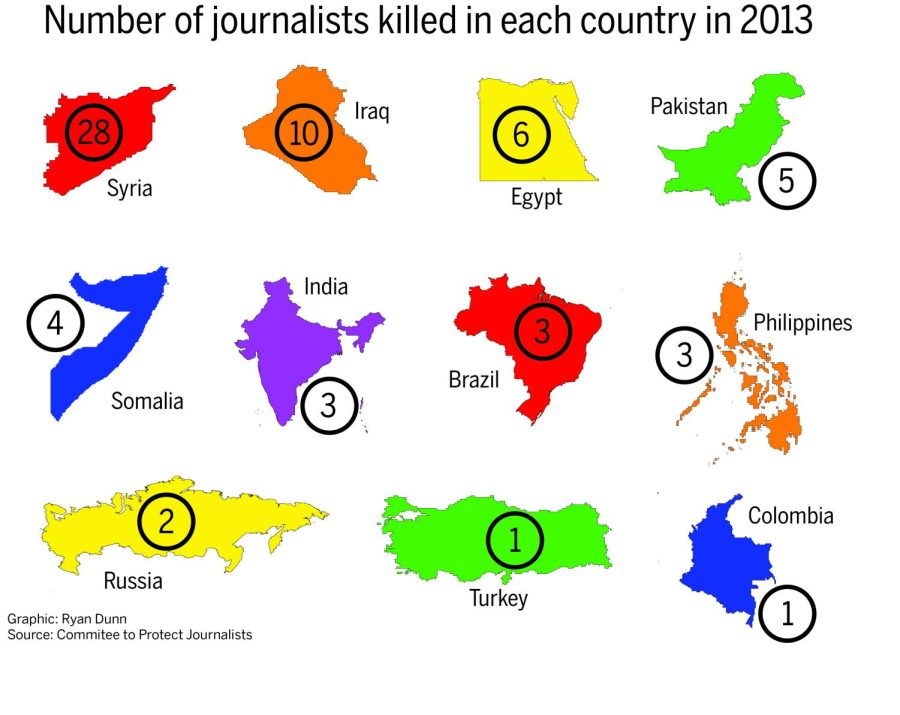

According to Reporters Without Borders’ 2014 World Press Freedom Index, areas controlled by ISIS are some of the most dangerous in the world for journalists. Syria ranked 177 on the list of 180 countries.

According to the report, 19 journalists were held hostage, detained or reported as missing in Syria between 2011 and 2013.

In recent years, foreign correspondents’ roles have evolved, as more journalists report in war-torn or politically unstable areas as freelancers, instead of with major news networks, said Joshua Stacher, associate professor of political science. Freelancers, without the benefit of news organizations’ correspondence and ensured security, are more likely to be taken captive.

Freelancers also tend to be bolder when covering a dangerous region, he said.

“If you’re freelancing, you have to be innovative, and you probably end up taking unnecessary risks,” Stacher said.

Over the last few decades there’s been a shift in militant organizations’ motives for detaining journalists, he said.

“Before, foreign journalists were things that you held, and you used as bargaining chips to extract things or get concessions from governments,” he said.

ISIS’s sequence of attacks, which targeted journalists and broadcast worldwide over the Internet, has affected the journalism community at Kent State.

John Bowen, adjunct journalism professor, said Foley’s and Sotloff’s beheadings were ISIS’s attempt to instill fear, and the media frenzy surrounding the attacks illustrates how fear influences the public.

He said the media’s job is to act as a watchdog for the public, and foreign correspondents’ roles, although risky, are that much more important.

“The media’s role is to ask questions, to challenge and to raise alternatives,” Bowen said.

Bowen said it’s important for international correspondents to educate themselves about the cultures they plan to immerse themselves in.

“You can’t go to the Middle East and not know anything about Middle Eastern history and culture and expect to be a decent reporter,” Bowen said.

Effective journalists, covering politically unstable areas, put themselves in the middle of the action, and as a result, in harm’s way, he said.

“(Journalists) are not going to be back in the safe areas,” Bowen said. “They are going to be out with the troops or villages because that’s where the real story is.”

Heather Inglis, a senior journalism major, said although news of the violence rattled her, it drives her to work harder.

“When I saw the story about James Foley…I couldn’t contain myself,” Inglis said. “I was very scared, and I cried.”

Senior journalism major Julia Adkins said the ISIS executions made her realize the potential dangers that can come with working as a journalist. Foley’s and Sotloff’s murders raised public awareness about the dangers that can come with the job.

Both Inglis and Adkins said they wouldn’t shy away from covering a story in a potentially dangerous region.

“I want hard-hitting news,” Adkins said. “I don’t want to be some reporter that stays swept under the rug.”

Contact Nathan Havenner at [email protected].