Kent residents debate fracking

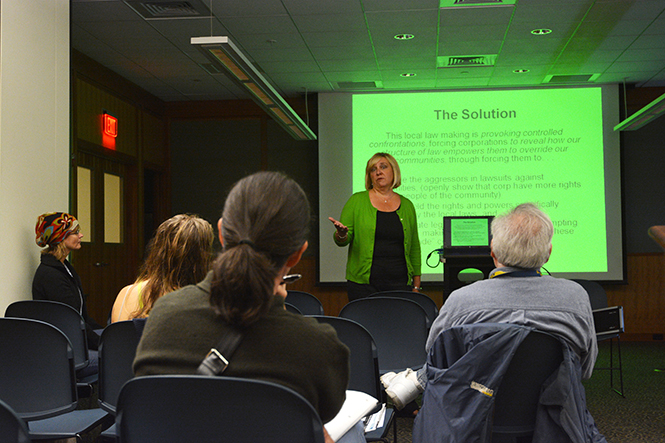

Tish O’Dell, the Ohio organizer for CELDF, Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, speaks to a group of 20 people in the Kent Free Library about environmental issues such as fracking, on Sept. 22. Photo by Jacob Byk.

September 22, 2013

Members of Concerned Citizens Ohio, and the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund gathered in Kent Free Library on Sunday to discuss how to protect their water.

Speaker Tish O’Dell, a member of CELDF and co-founder of Mothers Against Drilling In Our Neighborhoods, urged citizens to “think outside of the box” when going against the state government on environmental rights.

“Not only has federal law failed to protect our environment, the current structure of law prevents those communities most affected by environmental destruction from adopting local laws to protect themselves,” O’Dell said.

The process of hydraulic fracturing, commonly called “fracking,” involves injecting large amounts of fluid — a briny mixture of water, sand and other chemicals — deep into the earth. Once the drill reaches the desired location within the shale, the rock is fractured and natural gas is extracted.

The process has made natural gas more accessible, creating a hefty price drop among products relating to natural gas. Some fracking sites require several million gallons of water and chemicals that are largely unknown to the public because they’re determined to be “trade secrets.”

Assistant geology professor David Singer said some of the liquid blasted into the ground comes back to the surface, and this uprooted waste cannot be tossed into a normal landfill. Instead, the waste is injected back into the earth using disposal wells.

According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Portage County had 25 Class II injection wells as of Sept. 12 — more than any other county in Ohio. These wells are used to dispose of brines and other waste involved with oil and gas production.

Much of this waste is shipped across Ohio’s border from other states such as Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia and even Texas. Mark Bruce, spokesman for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, said Ohio is not allowed to distinguish where waste comes from — if a company refuses waste, it breaks Ohio’s interstate commerce laws.

“The underground injection is an established practice and, when done properly, it carries a low risk of contaminating drinking water,” Singer said. “I am personally concerned about transportation and storage of these materials and the potential for accidental release into surface environments. These fluids are brines — incredibly salty — and often contain elevated levels of naturally occurring radioactive material like radium.”

Singer said some fracking waste fluids have especially high radioactivity levels, and their contaminants exceed the maximum level set by the Environmental Protection Agency. Tanker trucks and river barges are known to carry these hazardous brines.

While many share the same concerns as Singer, others are concerned about what these chemicals might do to other aspects of the environment.

“The county is laced with poison,” Concerned Citizens Ohio coordinator Mary Greer said. “These elements and chemicals they are using are natural but only in their solidified state. Some of these materials are poisonous, especially if they were to be released in the atmosphere.”

Many Portage County residents are concerned about a decline in their property values because of truck traffic, well-water contamination and other issues revolving around injection wells.

Mark Brumbaugh said he is worried about his property and his neighbors’ properties on Webb Road north of Ravenna as well.

“Most everybody out here has well water,” Brumbaugh said. “Basically, if you have no water coming to the property, the property is worthless. All the money you put into your home, unless you get city water, is worthless.”

Portage County citizens Craig and Karia Lanken also are concerned about their property values. The couple lives on the outskirts of Ravenna and Kent.

“I was pretty proud when my wife and I bought a house out here, and now I’m thinking ‘What is this going to do to our property values?’,” Craig Lanken said. “We used to live in the city for years. We moved to the country because that’s what we enjoy and like because of the quiet, the solitude, the nature, and we are concerned that’s going to go away.”

According to ODNR, Class II injection wells use layers of steel piping and cement to protect aquifers from becoming contaminated. After the waste makes it down the long piping, ODNR claims the briny solution is trapped within the rock below.

“Industry says that due to our rock formations underground, we [Portage County] have the best way to hold this huge amount of poisonous water in place,” Concerned Citizens Ohio member George Sosebee, said. “But what’s happening underneath? Millions of gallons of poisonous water underground — where does it go? Nobody knows.”

O’Dell said people in her hometown, Broadview Heights, were not so concerned about their land being used for fracking or waste disposal wells at first. Many citizens owned small amounts of land.

“Wells were placed in people’s backyards on half-acres,” O’Dell said. “The people of the community don’t have a say, that’s been stripped from us.”

It is possible fracking sites or disposal wells could be placed within Kent or even on Kent State property. Kent State officials have the authority to deny or allow these actions on university property.

There are currently no official plans to frack on university land.

Kent City councilwoman Heidi Shaffer says the state wields a lot of power in these matters. The state has control over who gets what resources, and it is often difficult for local-level government to change that.

“I realize it’s very important to our economy,” Shaffer said. “We have some manufacturers who are benefiting from fracking, as well as property owners. They’re bringing in resources and providing jobs, but I think we’re selling out. I think we’re selling our future. We spent the last few decades cleaning up the environment, and now we’re willing to cause great damage again.”

O’Dell and her community created a Broadview Heights Bill of Rights and 10 prohibitions within the bill. O’Dell says her community has the right to Home Rule. Local people are the best to address local concerns.

“We’re always waiting for someone else to come and fix the problem,” O’Dell said. “It’s up to us, the people, to use our democratic rights they’ve stripped from us, and we didn’t even flinch, but we have to get them back. It’s up to us.”

Contact Rachel Sluss at [email protected].