Sandusky runs risk of sexual assault in prison

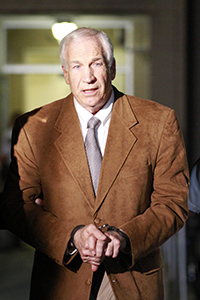

Jerry Sandusky leaves the Centre County Courthouse in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, at 10:15 pm, following guilty verdicts in his trial, Friday, June 22, 2012. Photo by David Swanson.

October 7, 2012

Associated Press

Because of who he is and what he’s done, Jerry Sandusky could be in particular danger of sexual assault when he is sent off to prison this week.

With thousands of inmates raped behind bars in the U.S. each year, statistics compiled by the federal government show that sex offenders are roughly two to four times more likely than other inmates to fall victim.

Sandusky, the 68-year-old former Penn State assistant football coach, will be sentenced Tuesday for sexually abusing 10 boys in a scandal that rocked the university and brought down coach Joe Paterno. Sandusky is likely to spend the rest of his life in prison.

It’s entirely possible that he will serve his time without incident. His lawyer, Joe Amendola, said he expects Sandusky will be housed with nonviolent offenders at a minimum-security prison, and the Pennsylvania Corrections Department said it is committed to the safety of all inmates, though it would not comment on what it plans to do to protect Sandusky.

But it’s also true that child molesters are reviled inside prison walls just as they are on the outside, and are often subjected to physical and verbal abuse, including sexual assault. Given the horrific nature of Sandusky’s crimes, will the public care what happens to him in prison?

“The Sandusky case is one of those moments when our core beliefs are really tested,” said Lovisa Stannow, executive director of Just Detention International, a group that fights prison rape. “This is a moment when it’s especially crucial to recognize that nobody ever deserves to be raped. No matter who you are, sexual violence and rape is wrong, it’s a crime, and it is something we have to fight.”

The U.S. corrections industry has long struggled with sexual violence.

In 2008, more than 200,000 inmates in American prisons, jails and juvenile detention centers were victims of sexual abuse, according to the Justice Department. Male sex offenders were among those at highest risk: Nearly 14 percent reported having been sexually assaulted at least once while incarcerated.

Yet experts say rape isn’t an unavoidable consequence of prison life. Justice Department statistics show wide variability in rates of sexual abuse across prisons and jails. Wardens who are committed to ending sexual violence, establishing clear policies against abuse and holding their staffs accountable are likely to see fewer problems.

“It’s all about management tone and style and leadership at the top. If you hear about abuse and sort of roll your eyes and look the other way, that sends a signal. If you tell the staff, ‘I want to get to the bottom of this,’ that sends a signal,” said Jamie Fellner, a prisons expert at Human Rights Watch.

In some ways, Sandusky, who has been held in isolation in a county jail since he was found guilty in June, is not a prime target for assault. Inmates who are young and small in stature are more likely to be sexually victimized; Sandusky is a senior citizen with an imposing frame. Other inmates at high risk include gay men, those who have been previously victimized and those seen as timid or feminine.

A convicted sex offender who spent 10 years in prison and now works with other released sex offenders through the Pennsylvania Prison Society said he believes Sandusky’s chances of assault are low.

“Are people going to bother him? Yeah, but a lot of it’s going to be verbal harassment — it’s not going to be physical,” said the 52-year-old man from the Philadelphia suburbs, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the stigma attached to sex offenses. “Because again, he’s an old guy; people aren’t into that. The verbal abuse is probably going to be significant. He’s going to have to have a thick skin.”

Lockups in Pennsylvania and across the nation are under a federal mandate to curb sexual abuse.

The rules, which took effect in August under the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, require screening to identify inmates at greater risk of sexual assault — and those more likely to sexually offend — with an eye toward keeping them apart in housing and work assignments.

Prisons must also offer at least two means of reporting abuse, preserve evidence, ban retaliation against whistle-blowers, keep juvenile offenders away from adult inmates, and devise plans for adequate staffing and video monitoring.

“You had corrections officials saying it’s not so bad, it’s not so bad, it’s not so bad, and then you had the data saying it IS so bad, it is a problem, it is prevalent,” said Fellner, who sat on the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, the panel charged by Congress with devising the new standards. “I think at this point, everybody understands this is serious.”

Pennsylvania’s policy for preventing sexual abuse dates to 2004. New inmates must be screened, and anyone determined to be at greater risk of sexual victimization is supposed to get his or her own cell, or be placed in protective custody or in a special unit for inmates in danger. Pennsylvania prisons hold about 6,800 sex offenders.

“Inmates and their families should know that we do our utmost to provide for inmate safety,” said Corrections Department spokeswoman Susan McNaughton.