Howie Emmer was one of the founders of SDS in 1968; Colt Hutchinson is the new president in 2020

April 30, 2020

When Howie Emmer came to Kent State University in 1965 from Cleveland, he remembers being asked by his roommate from rural Pennsylvania if Emmer would be wearing his rocketship pin each day. The pin was not a rocketship: It was a peace sign.

Emmer became an activist in high school, going door-to-door for Lyndon B. Johnson during his presidential campaign. He believed Johnson would de-escalate the war in Vietnam, something he says he felt betrayed about later when Johnson escalated the efforts instead.

In 1963, he became a student member of the Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland. As a white student, he joined a school walkout where 80 to 85% of public school students who were black stayed out of school to protest the conditions of the buildings.

In 1965, Emmer became involved in the anti-war movement, beginning in his later years of high school at Cleveland Heights before coming to Kent State. There, he became involved in the Kent Committee to End the War in Vietnam.

As a member of the committee, Emmer remembers one march in particular where about 10 to 15 students marched with signs against the war outside Bowman Hall while other students jeered and yelled at them.

“Yelling things at us like, ‘Go back to Russia,’” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘Russia? I’m from Cleveland.’”

Emmer says the decision to create a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter at Kent followed a protest at Columbia University in New York where a group of black students was joined by white students of SDS. The students took over university buildings until their demands were met. They had “two-pronged” demands: for the university to stop complicity with the war in Vietnam and to stop Columbia’s continued encroachment on and expansion into the black community by buying up parcels of land, Emmer says.

“Something that just moved us tremendously was, when the students took over the building, the New York police went in and beat the students big time in the process of arresting them,” Emmer says. “That contributed to me wanting to form SDS at Kent because SDS was the largest student organization of the time.”

SDS’ national organization had over 300 campus chapters created by 30,000 supporters as reported at the final national convention in 1969. At the convention, the organization broke into factions when different positions were taken concerning the Vietnam War, black power and other issues.

In 1968, Emmer helped start the Kent State chapter.

“We sat down in front of the old student union, and I remember it like it was yesterday, a few of us, a fellow named George Hoffman and a couple of others of us,” Emmer says. “We decided to form a Students for Democratic Society chapter at Kent State.”

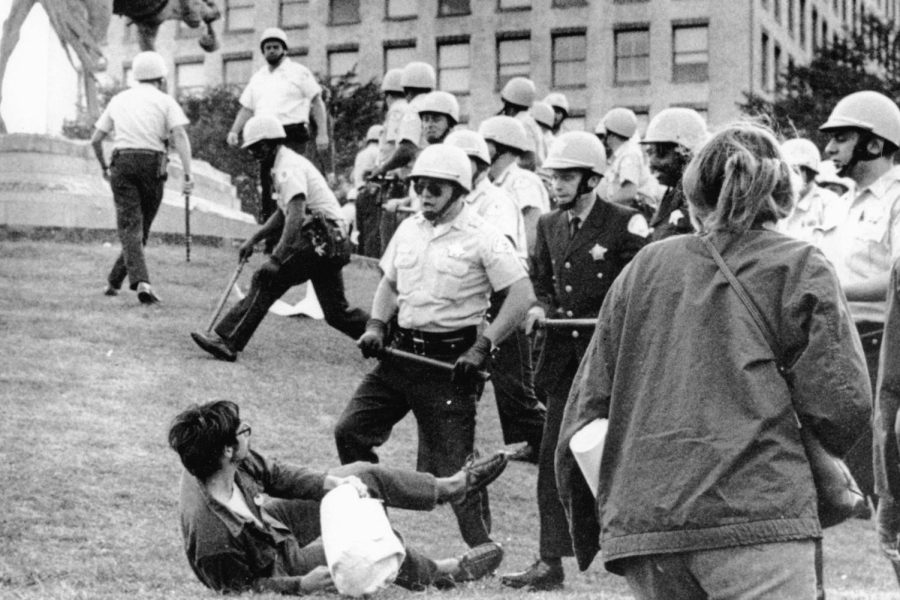

At Kent State, the first SDS meeting was held in fall 1968 following the riots at the Democratic National Convention, which Emmer attended. The protests were called for after Johnson announced he would not be running for president. Protesters came in the thousands to speak out against the Democratic Party for continuing to enable the Vietnam War.

Emmer watched as people linked arms while sitting in before police waded into the crowd and began to swing clubs at them, trying to break up their linked arms, and began arresting the protesters.He said that as the police descended on the protesters, a chant went up: “The whole world is watching.”

He believes this event brought more people to the first SDS meeting at Kent State, which he believes close to 100 people attended. Following the first meeting, an action committee and an education committee were created before the first tactic went into effect. SDS members built a coffin in fall 1968 to symbolize the death of the electoral college, because Emmer said college students were unrepresented by the elected officials. Students were angry that no one in power held their beliefs.

However, SDS at the university is not remembered for these smaller tactics, but rather their larger protests that began to set the stage for what was coming to Kent State in 1970.

Emmer remembers the SDS and Black United Students (BUS) joint takeover of the Student Activity Center building proudly. The groups were protesting the Oakland Police coming to campus to recruit students. The groups remained in the building until administration and campus police threatened to arrest them. Emmer said they thought they had made their point and prevented the Oakland police from recruiting, so they left.

Following the protest, leaders from BUS and SDS, including Emmer, were threatened with university disciplinary action. In response to this, every black student at Kent State walked off campus, setting up a freedom school in Akron. The students refused to return to campus until amnesty was granted to all the people threatened with disciplinary action. The university backed down, which Emmer said he thought was because universities wanted to appear that they were on the side of civil rights.

During the protest, Emmer remembers black student leaders throughout the takeover giving speeches and leading chants.

Emmer admired the “eloquence of the black students talking about what they faced, how few black students there were on campus, how isolating it was for them, how their culture and their needs weren’t respected and (sharing) their connection to the black liberation movement and the civil rights movement,” he says.

Following the protest of the Oakland police, Emmer says SDS remained dedicated to its anti-war cause, and a core group worked to keep the chapter active near the end of 1968, when the country became more polarized.

Emmer says students were angry that the government was “killing Vietnamese” in their names and not listening to student demands. He supports the silent vigils that groups such as the Kent Committee to End the War in Vietnam did, saying they did good work to bring people to a place where they were questioning the war. However, Emmer says SDS slowly shifted from protests to resistance, which made the government pay attention.

In spring 1969, the Kent State SDS Spring Offensive began

SDS planned on presenting a list of four demands to the president of the university, Robert White. Two had to do with the anti-war movement and two were focused on racism at home.

The first demand was for the ROTC to be abolished at Kent State. Emmer says ROTC produced second lieutenants for the Vietnam War who would direct soldiers overseas. He says they were angry that the university, a place for higher education and future careers, would be a key operator in this function.

The second demand was to abolish the development of liquid crystals for Project Themis. An SDS publication stated that Kent State was one of two organizations that researched liquid crystals, which were used in the Vietnam War. In the military, liquid crystals were used to detect heat, either from campfires or bodies when the crystals were dropped from aircrafts.

The third and fourth demands focused on the abolishment of the law enforcement school and the Northeast Ohio crime lab. Emmer said the point of these demands was to draw attention to police brutality. They were protesting the university having law enforcement on campus that harmed black people.

On April 8, SDS took these demands to the office of the university president following a rally and march. As they approached the doors, they were met by university police.

Emmer says SDS at Kent State was a minority in terms of their mindset against the rest of the university. They often received pushback from others declaring them communists or calling the movement unpatriotic. He remembers they continued their “no business as usual” plan to make people think about the government’s actions.

When SDS met the university police, a scuffle broke out, according to Emmer, who was in front of the group. SDS attempted to get into the building to deliver their demands as officers kept them back, and, following this demonstration, the university pushed back.

Emmer says the university came down on them “like a ton of bricks,” as if they had waited for this moment to punish SDS. The organization had their chapter decertified by the university and were removed as a campus organization. Emmer and others were charged with battery and assault on police officers.

“I will acknowledge there was some pushing, some of us pushed on some of the police officers,” Emmer says. “I did not do it. If I had, I (would’ve said) so more than 50 years ago, but I did not, but I was charged.”

Emmer and others were also suspended. He says after this, the tension between protesters and the university escalated.

Alongside other students facing arrest, Emmer hid out that night, so he would not be arrested off campus. He wanted the arrest to happen on campus during a rally to prove they were being arrested as political activists and anti-war protesters, not criminals.

During the rally the following day, Emmer spoke and noticed the police getting into formation, preparing to arrest him alongside Colin Neiburger and Jeff Powell, who went by the name Donovan.

“This was, to me, kind of a foreshadowing of the shootings a year later, a squad of police officers walked in an ultra-disciplined way. There must’ve been about 20 of them, long clubs held to their chests and face masks down,” Emmer says. “They were an attack squad and off-campus police force, and they went kind of in front of the administration building near the rally. And I was like, ‘Wow, this is really kind of a militarized presence.’”

Emmer’s arrest, among the others, led to bail bond collections by students at Kent State and friends and family in Cleveland. However, even though bail was made and they were released, Emmer and the others were served an injunction to stay off campus.

Neiburger was granted a conduct court hearing by the university, following the due process of being removed as a student from Kent State, but Emmer says they wanted more than just the hearing.

Emmer says he and Neiburger were fed up with the university being complicit in the Vietnam War, and they wanted to use the hearing to protest that.

“We were dedicating our lives at that point to being social justice activists and ending the war in Vietnam,” he says.

The original goal was for the students to use the hearing to explain why they took actions that led to their suspension. Emmer said they wanted to use the hearing as a forum to tell the university why they were protesting.

The plan changed when the university did not make the hearings public. Emmer believed the university did this to avoid an SDS protest at the hearings. When a police car came to the edge of campus to pick up Neiburger and Emmer on April 16, they refused to get in until the police told them where they were being taken: the Music and Speech Building.

Waiting with the two was another student, who was not banned from campus, who then ran to the SDS rally taking place at that very moment and spread the word of where the hearing was.

When the SDS rally marched to the building where the hearing was taking place, they were met by a crowd of pro-war students, Emmer says. When the groups collided, a fist fight broke out. SDS members found a side door to enter the building, and 70 members made it inside.

Emmer had been yelling out a second-story window, alerting the students where the hearing was. Police locked the building, turning the protest into an unplanned takeover, and began arresting protesters.

Emmer believes about 67 people were arrested. He was arrested for inciting a riot and served six months in the Portage County Jail in Ravenna.

When so many people were not allowed on campus, Emmer says meetings were still held and actions carried out, mostly led by the women of the former chapter of SDS.

Colt Hutchinson (2020)

Colt Hutchinson grew up in Marietta, Ohio, right along the West Virginia state line. He is a junior double majoring in political science and jazz. He is sitting inside the Kent State University Library’s May 4 room, just a few days before the new SDS would take their first action in the new decade.

Huchinson says that while there are other left-leaning organizations on campus, SDS will be more active, looking to do more than social events and hoping to push people forward. This new SDS is part of a national organization of 120 chapters that was created in 2006.

Kent State SDS held its first protest about the war in Iran on Jan. 25, 2020, as a part of Global Protest Day. The group ended up moving inside due to weather conditions and hosting a teach-in where all participants could discuss the war and the sanctions, according to KentWired, Kent State’s student-run news website. Hutchinson says they had about 35 people join.

“SDS is a direct action organization. That’s very fundamental to our beliefs,” he says. “Historically, all change that has happened in America, or anywhere, has come from people being on the streets, out in public and very visible strikes, boycotts. We’ve just planned to be very visible, to be a present force.”

Hutchinson says SDS is different from the political groups on campus because it is supposed to be more of a unifying organization, pulling people from different areas to focus on key issues they can work on together. While some political organizations work on one specific target, such as supporting a candidate, SDS wants to focus on local issues and promote change for students on campus while also getting them involved in progressive causes.

On Feb. 11, 2020, SDS, joined by BUS, Students for Justice in Palestine, Jewish Voices for Peace, Young Democratic Socialists of America, United Students Against Sweatshops, and Threads marched into President Todd Diacon’s office holding a codified list of four demands, echoing the demands of the original chapter.

According to Hutchinson the four demands are:

1) for a “proper” committee for May 4 that involves students and public meetings;

2) removing Aramark from campus;

3) a student workers contract;

4) and a joint fourth demand for the university to protect students’ health and safety specifically concerning the mental health services on campus.

After 1970, both the university and student groups held memorials. Since the May 4 Task Force was established in 1975, it has continued the tradition. But for the 50th anniversary, the university has taken charge of the events.

In March 2019, the Board of Trustees passed a May 4 resolution stating, “That for the continuity and sustainability of these efforts, the time is right for the university to assume responsibility for annual May 4 commemoration and ongoing educational events through the Office of the President, beginning in 2019-2020 and continuing from that time forward.”

The conflict with the new planning committee is that only two students serve on it, Hutchinson says. Other members of the committee include family of the students who were killed, family of those wounded and those who were wounded themselves. Among the members are Alan Canfora, who was shot in the wrist on May 4, and his sister, Chic, who ducked behind cars in the Prentice Hall parking lot.

The trustees’ 2019 resolution passed following the publication of an open letter from the May 4 Task Force that said, “Our future is being decided for us without us. We believe this resolution will give the university the authority to hold the commemorations after the 50th and become the main educational body for May 4. Many current and former Task Force leaders have objected to this proposal.”

“My concerns (are) that they are systematically wiping out the history of student activism and the antiwar movement with May 4, and they’ve turned it into this thing where the line they’re pushing is remembrance of the four students,” Hutchinson says. “I can understand it if you want to remember these four students who lost their lives, but if you’re only talking about these four students then you lose the picture of what (students) were fighting for.” Of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller were actively protesting on May 4.

The second demand is for the university to remove Aramark as the company running Kent State’s dining program. The food provider is linked to public and private prisons and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Instead, the coalition wants the university to create an internal dining service system and remove all third parties.

The third demand is for the university to create a student worker contract that would pay students a wage of $15 an hour, referred to as a living wage.

Students working under Aramark in dining services are contracted by the company and paid minimum wage; they are not paid by the university. The minimum wage in Ohio is $8.27 per hour and student workers are limited to working only 28 hours a week. International students cannot work more than 21 hours.

The last demand is for protection for students, both concerning the availability of on-campus University Psychological Services and in regard to the growth of white nationalism across the country.

Hutchinson says another issue that goes along with the four demands is the lack of transparency at the university on multiple issues, specifically in planning May 4 commemorations.

Howie Emmer supports the new SDS work alongside other student organizations and their new list of demands. He knows they face different problems than when he was leading SDS and can see it in the tactics they employ, but at the core the organizations are the same.

“We did also believe that there’s something rotten at the core of the way our country is run, politically, economically, militarily,” Emmer says. “There’s power that is wielded in the hands of relatively few people for the sake of maintaining the power and the wealth of relatively few people.”

Emmer believes that a major difference is the advancement that Hutchinson’s generation has in terms of gender issues, which Emmer himself did not fully know about until the Stonewall Riots in 1969, even though he became an activist in 1964. He says that Hutchinson’s generation is more prepared to educate and create a movement around those issues compared to past groups.

When it comes to tactics, Emmer believes those change depending on what the time period calls for. He believes the most important thing is that the organization is educating people and taking whatever action is appropriate.

The new SDS adviser is Idris Kabir Syed, an associate professor in the Department of Pan-African Studies and former adviser for the May 4 Task Force. He was approached by Hutchinson in the fall 2019 about restarting SDS.

Syed wants to be a point of reference for students, someone who can be of assistance while letting them make their own calls and set their own agendas. He worked with Hutchinson to set up the chapter but said Hutchinson had been communicating with the national SDS organization as far back as spring 2019.

“Those of us who’ve taught the May 4 class and teach a lot of social justice and activist-oriented courses here are aware of how much students of today are looking back to the time period of the late ‘60s, in terms of the issues they face today,” Syed said. “So many of those issues are so relevant in the modern world. We’ve got a lot of issues that are very much like they were 50 years ago. I think students are struggling to try and find ways to be active and have an impact on the society around them.”

Syed said the communication between SDS and the other progressive groups on campus is evident between the growth of the group from five or six people to 15 to 25, and that the representation of the group’s other issues solidifies SDS’ goal of being a unifying organization.

The main goal of SDS as the 50th commemoration of May 4 approaches is for the organization to continue to educate the campus about student activism, especially the historical role it played at Kent State, Syed says.

“I look forward to commemorating May 4,” Emmer says. “I do think it’s really important that the message of May 4 be that what’s being commemorated is that we should be honoring students who stood up and took risks standing up against any illegal, unjust war being fought in their names and the horror of the official U.S. government’s repression of protest. That’s the heart of it and I hope that is the central theme and message.”

The above article is from this semester’s special edition of The Burr that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the May 4, 1970 shootings. To read more, visit the full magazine on TheBurr.com.

Madison Macarthur — [email protected]