OPINION: With bipartisan support, it’s time to stop Ohio from executing people

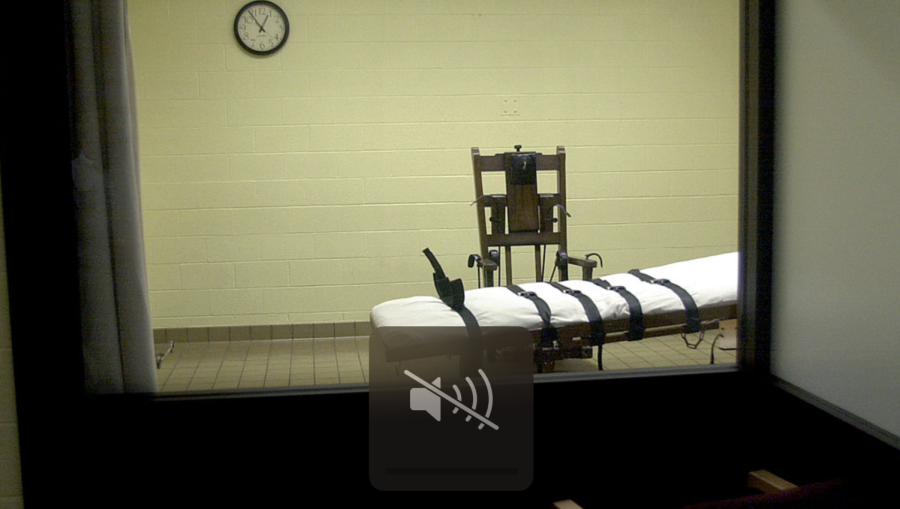

A view of the death chamber from the witness room at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility shows an electric chair and gurney. (Photo by Mike Simons/Getty Images.)

April 5, 2023

OHIO CAPITAL JOURNAL– Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost appears to have used a normally factual state report on the death penalty to make his case for resuming executions.

Going back to when it was first issued by AG Betty Montgomery, the Ohio Capital Crimes Report provided a valuable record of all executions and death penalty cases in Ohio. It is required to be issued by the Attorney General each year by April 1.

Over the years, the Capital Crimes Report showed the status of all capital cases, including those that ended in executions. The document contains details on where cases are in the legal system, a complicated and confusing process that often takes 15 to 20 years or more. The most painful part of the report is the brief summary of the crime in each case. They paint a grim story of murder, mayhem, and cruelty beyond imagination. It is hard, as a reader, not to think that the killer, if guilty, should not be allowed to walk among us.

Yost, a Republican death-penalty supporter perhaps eyeing a future run for governor, transformed the 2022 report into a personal campaign to fix the “state’s broken capital-punishment system.”

Translated, it appears to mean he wants to kill more people.

Yost, a former county prosecutor, dutifully includes all the facts in the report, but goes on to lament the state has executed only 56 people out of 341 death sentences issued since 1981 (FYI: The state didn’t resume executions until 1999 and has not had an execution since 2018 because of lack of drugs used for lethal injections.)

His move in this direction began, at least in a public sense, when he met earlier this year with Norman Stout, victim of a 1984 home invasion near New Concord that resulted in the death of his wife, Mary Jane. Yost publicized the meeting in advocating for greater emphasis on victims in capital cases. John David Stumpf, the man convicted of killing Mary Jane and critically wounding Norm Stout, remains on Death Row after 39 years.

The Executive Summary of the new Capital Crimes Report, written by or echoing Yost’s opinion, says the system “is not equally or promptly enforced, and because of that it invites distrust and disrespect for the rule of law.” He argues that the long appeal process is cumbersome, delays justice for victims, and costs taxpayers far too much money. And he sympathizes with jurors who handed down death sentences only to see 1 in 6 resulting in an execution.

Yost questions the idea of “exonerations,” arguing that there are a very few actual innocence cases.

In fairness, the Attorney General suggests some changes could be made, including requiring more than one eye witness in murder cases, and more specific evidence such as DNA or a video confession.

Many of Yost’s complaints are valid.

While I disagree with my former newspaper colleague (Yost was a reporter long ago) on nearly everything, I agree the system is broken. It is badly skewed against minority and poor defendants, suffers from radical geographic disparities, plus instances of incompetent lawyers, and unscrupulous law enforcement and prosecutors. Victims have a voice through the prosecutor and a Crime Victims representative.

The accused is represented by attorneys, typically a state or federal public defender. Left out of the equation almost entirely are families of the convicted killers who, in a sense, are about to become victims themselves.

As a reporter for the Columbus Dispatch, I personally witnessed 21 executions and wrote about dozens of others. I maintained an objective point of view throughout 44 years in journalism, the last 33 years in Columbus. I kept my opinions to myself in print and in person.

But after I left journalism, and not coincidentally after I went to theology school, I became convicted that the death penalty was morally, spiritually, ethically, and financially wrong. All life is sacred.

Yost downplays dozens of cases which resulted in exonerations, where decisions were reversed by the courts, or the governor granted clemency. I know these exceptions for a fact, having written about many of them prior to my retirement in 2017.

One case stands out. Tim Howard and Gary James, two Columbus men charged in a 1976 bank robbery and murder, were exonerated in 2003 as not guilty after being behind bars for 27 years, part of the time on Death Row. Their death penalties were overturned when capital punishment was found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, but they remained incarcerated for life.

The Howard and James case had all the markers of injustice: false witness identification, missing and withheld evidence, no film in the bank surveillance cameras, investigative abuses by a corrupt police officer, and legitimate alibis conveniently ignored. They were railroaded.

The wrongful prosecution ended up costing Ohio taxpayers $4 million in a court settlement, the largest in state history at the time. Similar settlements have happened since. Yost would prefer you forget about those.

There have been 191 innocence exonerations from capital cases nationally since 1973, 11 in Ohio, including Howard and James, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

My personal and firm belief as a Christian is that killing people to punish people for killing is wrong. Yost, who professes Christianity, must deal with that in his own mind.

In his official screed, Yost says, “Either make capital punishment an effective tool for justice or eliminate it.”

Easy. End it.

Bipartisan legislation has been introduced in the General Assembly to end the death penalty.

Do it. End killing by the state of Ohio.