I am the daughter of immigrants

September 4, 2019

He was like a washing machine, my dad.

Cycling through tasks, moving mindlessly, over and over. He worked at Parker Steel Inc. in the daytime, returned home to eat and sleep, then drove to his second job mopping floors at a Kroger store while the rest of us dreamt under soft covers.

I remember walking downstairs to the kitchen for a glass of water at probably 5 in the morning, just as he tip-toed inside. He did not want to disturb the dog, who would wake everyone else, or my mother, who was never good at sleeping anyway.

I looked into his tired eyes. “Hi, Papa.”

“Hi, Lerochka,” he said, greeting me with my Russian childhood nickname, and a soft smile. He took a sip of orange juice from the carton. “I’m going to sleep, OK?” This was the extent of most of our conversations during my high-school years, when my parents took on evening jobs to make extra money. Dad walked wearily to the bedroom he shared with Mom, where he set his alarm and shut his eyes. He was readying himself to do it all over again.

Cleaning grocery stores and doctors’ offices wasn’t unlike jobs Mom and Dad had done before. My parents and two siblings are immigrants from Ukraine. This month marked 26 years since they packed their lives into suitcases and waved goodbye to their mother country. The economy was failing, the politics were in turmoil and the air they were inhaling hadn’t felt safe since the Chernobyl nuclear power station exploded in April 1986, blanketing the Soviet Union and much of Europe in a cloud of radioactivity.

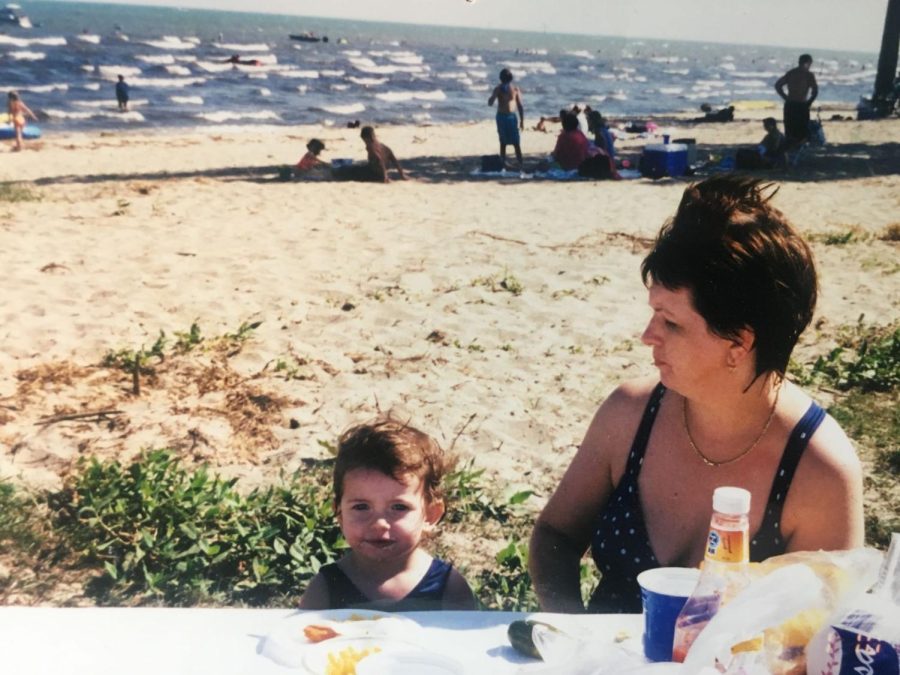

When I was little, I didn’t think anything of my parents’ many jobs. When my brother and sister were in school and nobody could babysit, Mama brought me to work. Sometimes we’d spend time with Dora, who I remember had an entire shelved wall of antiques and trinkets. And, I think, a pink-tiled bathroom. My mother was Dora’s caregiver, cooking and cleaning for her, as well as helping her bathe and get dressed.

Later, when Mom worked full-time as a hairdresser, I twirled around in beauty salons and looked myself up and down too much in the mirror as she cut her clients’ hair. I remember eavesdropping on their conversations. Mom always had gentle hands and left everything better after she touched it, especially hair. It’s why she could still play the violin and piano after years of setting them down and why her cooking is still one of my favorite things in the world.

As I got older, I realized my parents were always working. When they first arrived in Toledo, Ohio, they worked as babysitters and dishwashers to pay rent and buy groceries. They worked to learn English, to pay back Jewish Family Services for their plane tickets and housing costs, to prove themselves as dedicated Americans. They worked to buy a car and afford clothing that didn’t come from Goodwill.

When my mother gave birth to me in 1997, I was a United States citizen before she was.

Mom and Dad wanted their three children to go to college and pursue careers that meant something. They don’t want me to mop dirty floors for a living, unless they’re my floors, in a house that I own.

I’ve chosen to be a writer. It’s not exactly the most strenuous job, interviewing people and sitting in front of a MacBook screen and growing frustrated when I can’t seem to pinpoint the right word.

I carry around guilt knowing I’ll never need to do the same work as my mother and father. My hands will never be as soaked in bleach and cut up from metal scraps as theirs. I also carry this guilt understanding I was born into a life of privilege. I didn’t have to leave everything behind and cross the Atlantic into a foreign country.

But hard work will take you where you let it. It’s led me to storytelling and Kent State’s journalism school, and I often find myself searching for my parents in the stories I write about. These are stories of real people, stories of struggle, stories that kindle the spirit. Sometimes I wake up early to finish assignments and revise my writing, and I imagine my father’s tired eyes from years ago.

I recognize myself in them. In one eye, I see the reflection of the high-school girl whose parents were ready to sacrifice so much for their daughter’s future. In the other, I see the college girl ready to turn those sacrifices into the opportunity my parents sought when they stepped foot on American soil.

This makes me think that my guilt is really gratitude, that my work is my way of honoring my parents.

I will always be a daughter of immigrants.

And I am proud of that.

Valerie Royzman is a contributor for A Magazine. Contact her at [email protected].

This story was originally published on A Magazine’s website.