Students devise campaigns to address Trumbull County’s alarming opioid epidemic

May 13, 2018

It’s no secret the opioid epidemic — declared a nationwide public health emergency by President Donald Trump in October — is grabbing hold of Ohio, as the state ranked second in the nation for drug overdose death rates in 2016.

It’s especially harrowing in small, rural counties like Trumbull, which had the highest overdose death rate in all of Northeast Ohio from 2011 to 2016, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

In 2016, the epidemic claimed 111 lives in the county, an increase from 54 in 2014 and 89 in 2015.

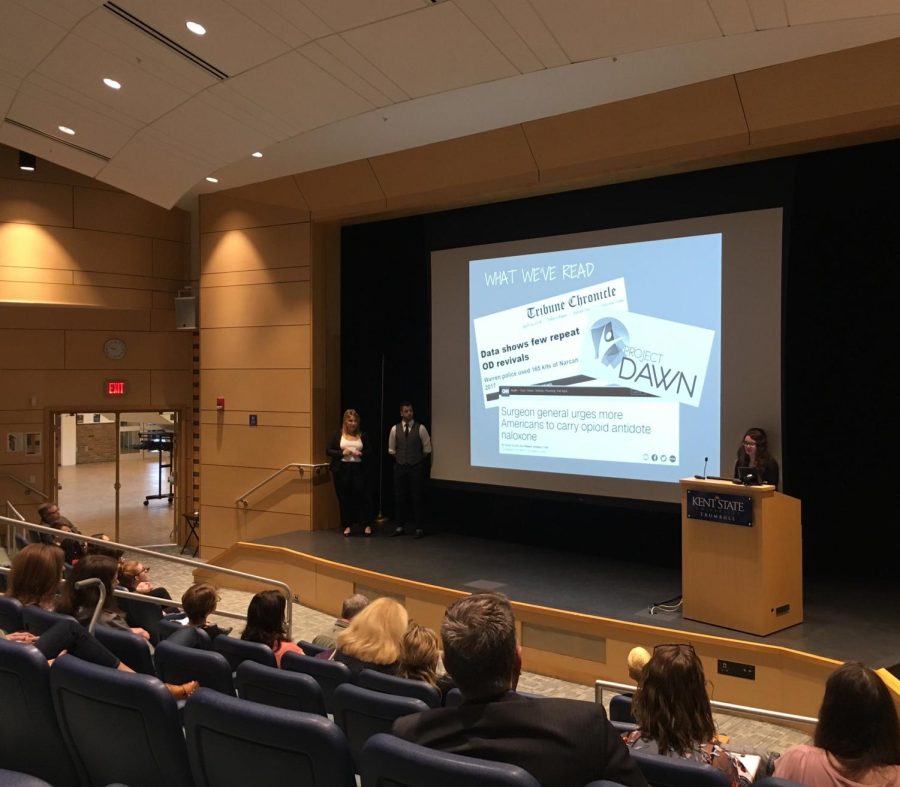

On May 4, Kent State students part of a course on the opioid crisis presented campaign ideas to the Alliance for Substance Abuse Prevention of Trumbull County, or ASAP, in hopes of spurring change in the midst of the epidemic.

The semester-long course, “Media and Movements: The Opioid Epidemic Seminar,” was centered around advocacy in the Trumbull County community, where students conducted more than 200 interviews with residents.

Stephanie Smith, an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication who taught the course, said it pushed students to “go where it’s hard, where it’s gritty and where the news is not good.”

The course was composed of public relations, journalism, communication, visual communication design and nursing majors — some of them with a direct family tie to the epidemic — who shared their campaigns at the Trumbull campus.

The first team’s campaign, called Practice Positive, focused on a non-school related drug prevention program for children. The group tailored their campaign to children ages 9 to 12 because they fall into the “risk zone” for drug use, meaning they’re more likely to be exposed or face peer pressure.

Practice Positive revolves around a made-up character, Pax, who is neutral in gender and ethnicity, aimed to encourage children to make smart decisions, especially in situations involving peer pressure.

Pax was created based on responses when the group asked children to draw their role models, which generated pictures of parents and relatives, along with athletes who “were committed and practiced every day,” one member said.

The campaign is intended to reach athletes, children who attend church and disadvantaged children involved with after-school or summer programs. Practice Positive members designed 10 lesson plans for instructors to implement in after-school activities, like youth clubs or sports clubs.

The second campaign, Everybody Knows Someone at Risk, concentrated on research that found Trumbull County residents are aware of their risk for addiction. The campaign’s target audiences included those most susceptible, but also residents easy to reach.

The group decided to address high school athletic coaches because of their influence on students’ lives and research that shows it’s common for opioid addictions to stem from high-impact sports injuries. The team presented posters to hang in locker rooms.

After visiting local bars and finding a strong correlation between alcohol and drug use, the group wanted to educate bar patrons, too, designing glasses, coasters and matches with their logo.

Movie theater-goers were part of the target audience as well, as the theater is a place where many Trumbull residents of all demographics congregate. Team members later brought out examples of movie posters with their logo and messages.

The group spoke of attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings, which inspired it to create an app, called Be Mindful. It’s meant to reach people beyond their ties to addiction, and it would ask daily prompt questions like “How can you be mindful today?”

Can You Imagine?, the third campaign, asked Trumbull residents to picture a world without Band-Aids, then asked what they’d do if they only had three for an entire lifetime.

The idea came about after the group’s research found some residents believe three overdoses should be the limit for the use of naloxone (also known as Narcan), a life-saving drug that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.

Both Band-Aids and Narcan are temporary, but effective, tools to healing, one member said. The campaign focuses on promoting awareness of access to Narcan in the area.

The campaign aims to reach parents ages 25 to 45 and increase their awareness of Narcan availability, and it encourages them to educate their children. Trumbull residents ages 55 and older are another target because of their concern with using tax dollars to pay for Narcan. Group members discussed that religious officials could help, as the clergy in the county they interviewed were in support of saving lives, no matter the circumstance.

Finally, nursing students’ input played a role in the campaign, as they will be entering the field professionally and working with patients affected by addiction.

Rachel Dalton, a sophomore nursing major, spoke after the team’s presentation and expressed that the use of Narcan isn’t brought up enough in class.

“We do talk about Narcan, but it’s just brief; no one really discusses it,” Dalton said. “I, myself, have experienced patients on opioids and who have had a heroin addiction. … I definitely think Narcan should be talked about more in the nursing field.”

Nursing students are not taught how to administer Narcan, she said, though she wishes they were because “our motto is to save lives.”

The final campaign, Hope Dealt Here, posed one question to Trumbull County residents: “What does hope mean to you?”

The group crafted three key messages based off responses, which urge residents to be kind, look to the future and believe in something bigger than themselves. A member of the team created a website, using pop art as the inspiration for the logo because the bright neon colors are intended to grab the attention of residents.

The campaign focuses heavily on community outreach work and the hope to involve schools and small businesses to spread their message. “Hope dispensaries” would be placed throughout the county, containing kindness coupons to use at local businesses, book boxes for visitors to take and leave books and “attention-getters,” like art or messages of poetry.

Lauren Thorp, the director of recovery and youth programs for the Trumbull County Mental Health and Recovery Board, said all of the campaign ideas hold a place in Trumbull County.

“This crisis — it’s not just one thing, it’s multi-faceted,” Thorp said. “Prevention is helping kids make good choices, to be more resilient. Then we have the Narcan issue and do enough families know that Narcan is available to them? We have it for free, but we know not everyone is taking advantage of it.

“Hope can help the person that’s addicted now get into treatment; hope can help somebody from not trying drugs in the first place.”

She added “knowing your risk,” especially for young athletes, is important in the community.

Thorp will take the campaign ideas and present them to the ASAP coalition, led by the Trumbull County Mental Health Recovery Board.

After the presentations, Smith, who is a Trumbull County resident, said the county is “disproportionately affected,” and praised her students for their willingness to be unafraid in tackling the epidemic.

“Both Kent campus and Kent State Trumbull are rolling up our sleeves; we are not ignoring it, we are investing our time, our energy and our best talent into it,” Smith said. “We’re going to put our oar in the water, and any ripple we make, we’re just going to hope that it leads to something greater.

“And we don’t have the self-aggrandizing view that we’re going to create a tsunami of change, but we’re unafraid to say, ‘If we do one thing, that’s important.’”

The all-consuming crisis isn’t slowing down in Ohio, and Smith said the role of young people during this time is crucial for raising awareness on addiction.

“I think the most important thing is to make other people aware that it is everybody’s problem,” she said. “It is a public health problem; it is a disease. It is a chronic, relapsing disease. That is not a social weakness; it is not a moral weakness.”

Everyone is vulnerable — “one bad surgery, one backache, one nasty fall” away — to potential exposure to opioids, she added.

“If every young person could know one thing — if you can tell one story, tell it,” she said. “Care enough and know enough to tell it well. It’s everybody’s responsibility.”

Valerie Royzman is an administration reporter. Contact her at [email protected].