“Burnt-out”: college students experience mental health decline

November 20, 2021

College students nationwide are feeling the pressure of returning to in-person classes as demand for access to mental health services has been at an all-time high. Campus administrations attempt to accommodate the mental health of students as the workload and stress levels increase for students across universities.

“Burn-out,” or the feeling of work overload, is increasingly common for college students who decided to return to the college curriculum. Scrolling on social media and online college community groups, almost everyone has something to say about the increasing amount of stress.

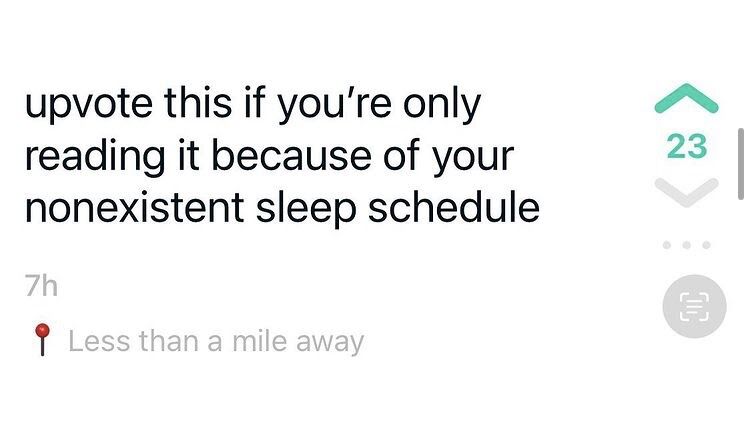

“Upvote this if you’re only reading it because of your nonexistent sleep schedule,” and “Kent read kent write kent go a day without sobbing” are just a few of the anonymous posts shared on the social media site Yik Yak. Anonymous users in the area, most likely Kent students, can “upvote” posts they agree with, and these two posts earned at least 50 upvotes.

In October, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill canceled classes for student “wellness” days after two deaths by suicide were reported since the semester began. It resonated nationally at a time where students feel particularly overloaded.

What exactly is causing this heavy burden? A recent study found by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that more than 10 percent of adults surveyed in June 2020 have seriously considered suicide within the past month. Among 18-to-24 year-olds surveyed in 2020, the CDC said about 25% had seriously considered suicide. The most recognized cause of this heightened workload and depression statistics is the simultaneous ongoing and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the fall 2021 semester, Megan Pearce, a junior psychology major, was enrolled in one in-person class while the rest were online and she believes the pandemic has heavily impacted the typical college experience.

“I feel like it [mental health] is harder, although it has improved,” Pearce said. “But it still is hard at times because you’re not getting that face-to-face that some people need.”

She still accredits the university for handling mental health on and off-campus and notices when professors make extra efforts to offer resources and see the strength in asking for help, she said.

“I know for my Abnormal Psychology class, we talked about suicide, and there was a national hotline at the end of the PowerPoint,” she said. “By reaching out to your professor, I feel like that would be a good step into getting the help that you need.”

In this ideology, she is certainly not alone.

In fact, there are a variety of mental health resources on campus available to students throughout the semester. One mental health professional at Kent State is Dr. John Schell, the associate director for Counseling and Psychological Services, also known as CAPS. The department is located in the Health Center on campus and Schell has worked there for 21 years.

“Our role is really to support students and help them kind of navigate their mental health issues,” he said.

Schell’s department offers several programs for students who might be struggling, with individual and group counseling free of charge. The group counseling sessions allow students to meet virtually with psychological professionals to discuss specific concerns.

Emily Lian is a sophomore psychology major and has been receiving mental health services since she was thirteen years old.

“Being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety and an obsessive-compulsive disorder, I can say I’ve gone through the wringer with different intensive treatments and interventions, “ Lian said.

Lian and her therapists in the past concluded that her diagnosis comes from childhood trauma. This year they have been working together to heal her inner child through trauma therapy.

“I believe we’re all products of our environment and the behaviors that are modeled to us as a child,” Lian said, “The trauma I went through basically rewired my brain and I’ve never been able to heal that.”

Going to college and becoming a bit more independent, Lian said she was able to utilize therapy with counselors she trusted. But therapy isn’t the only course of action Lian has taken to help her cope with the weight of her diagnosis. She started implementing meditation and breathing techniques to help manage any overwhelming emotions.

“In my healing process I’ve taken the step to recognize what my thoughts are when I’m making a decision or how I choose to react to things,” she said.

The healing process can be a plethora of options that students and young people have a choice in what is most comfortable for them.

Dr. Jason Miller, director of the Counseling Center, oversees group and individual therapies for students on and off-campus. The center is located in White Hall, Room 325, with roughly 223 appointments occurring every week, between 60-80 of which are remote.

One distinctive factor of the Counseling Center is that higher education students give the services almost entirely.

“The counseling is provided by masters and doctoral students in the counseling program, some of which are already licensed counselors in the state of Ohio,” Miller said.

He oversees the students and the program as a whole and helps other Kent faculty members in program supervision overall. To Miller, students’ primary mental health issues have always been the same, even before the pandemic.

“Our top presenting concerns are anxiety, loneliness and depression,” he said.

However, these concerns have gotten worse over time. Isolation, general health and the political spectrum are just some subjects that have worsened mental health. For example, Miller said there was unwanted solitude as a result of the pandemic.

“COVID has impacted loneliness … even just with the remote classrooms and stuff,” he said.

Less time in classes means more time alone, and students have been experiencing increased feelings of alienation in turn, Miller said. Additionally, anxiety surrounding health concerns has also risen in students.

“I think COVID has increased anxiety based on people’s personal needs … in terms of wearing masks, getting vaccinated and reading the news, to name a few factors,” he said.

Similarly, he said depression might make it so that students don’t want to get out of bed in the morning and deal with the heaviness of the external world. This also relates to overall feelings of tiredness, which can be induced by large amounts of screen time, whether from classes, homework or pleasurable purposes. This heaviness has been made apparent to campuses and their cities nationwide, and the university has been committed to it’s mental health expansion and access for students.

Joan C. Seidel, the Kent City Health Commissioner, said Kent State has increased its capacity for psychological services on campus because they see the need to serve its students.

More updated info here about the KSU mental health expansion.

“I know sometimes when you’re depressed, it’s hard to be motivated about your care,” Seidel said. “Sometimes people are hesitant to use services on campus, and there are different places that people can turn to if they’re feeling more anxious than usual.”

Morgan McGrath is a reporter. Contact her at [email protected].

Natalia Hernandez Maceira is a health reporter. Contact her at [email protected].

Annie Zwisler contributed to this report. Contact her at [email protected].