SI leaders utilize playful, non-traditional group study methods

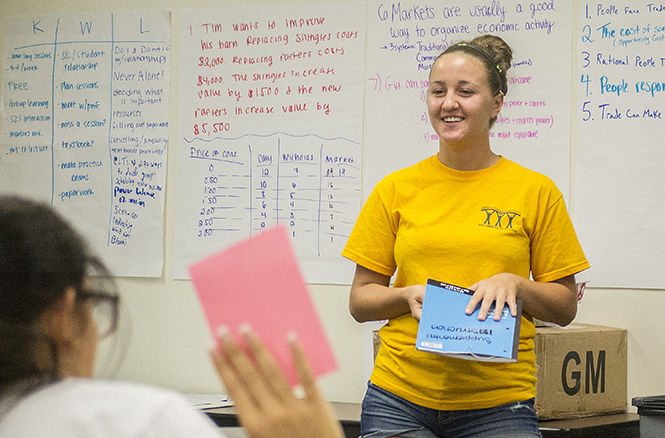

Supplemental Instruction leader Maggie Evans asks students questions for a review quiz on biology and postulates in the Schwartz Center on Tuesday, Sept. 9, 2014.

September 16, 2014

Freshman Sara Formoso stood in the middle of Room 207 at the Schwartz Center and pointed a six-shelled blue and orange NERF gun toward the front of the classroom. She looked indecisive.

“Go ahead,” Maggie Evans said.

Formoso fired, hitting a large sheet of paper taped up on the whiteboard that has “HYPOTHESIS” written near the top. She turned to Evans.

“Very good!” Evans said, and handed the toy gun to the next student.

It’s certainly not the most traditional way to learn the scientific method.

Evans, a senior integrated science major, has been an SI leader for almost as long as she has been at Kent State — seven semesters. She talks about organelles and mitochondria with students with an athletic pep, sitting on a desk in the back of the room. She boasts an old golden SI T-shirt with a faded logo. She’s been an instructor so long her co-workers call her the “Grandma of SI.”

Evans’ technique of helping students with cellular biology is just something typical among other SI Leaders at Kent State, a part of the Academic Success Center’s Supplemental Instruction program. Rather than tutoring one-on-one, SI Leaders take advantage of a group atmosphere, turning “historically difficult” class material into something that Evans believes can be “fun” — and also productive.

“Studies say that you can learn two and a half times faster with a group,” she said. “Or something along those lines.”

Based off of the educational psychologies of Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget, Deanna C. Martin created SI at the University of Missouri in 1973. Noticing that there was a 30 percent D-grade dropout rate for onerous classes such as logic and biology, Martin aimed to fill the gap left between professor and those taking the class with a student-run educational “supplement.” It’s a model that was adopted by Kent State in 1999.

Stephanie Jain, SI program coordinator, said that SI “fills this gap” via a connectivity not found in 300-plus person classes such as general psychology. Since all SI Leaders have taken their designated course — and gotten an ‘A’ — Jain said their knowledge and professor-specific experience make these student instructors the best form of connectivity between professors and the material lectured on in class.

Jain also said a small group setting makes for a learning atmosphere not readily found in many chemistry, biology and psychology courses. An SI session, she said, is where students can actually talk to one another on a communicable level while simultaneously “taking their own responsibilities for their learning.”

In such a way, SI may be needed by some, Jain said.

“One of the reasons that it is so hard to learn in a lecture is because you’ve got one expert explaining the concepts in one way to a group of 100-plus (students),” she said. “But in an SI session, you get several levels of knowledge coming together, along with activities that make it more meaningful.”

For such activities we turn again to Evans.

Other than selecting parts of the scientific method via NERF ammunition, Evans has other tricks up her sleeves. She often hands out biologically themed crossword puzzles, and might spend the beginning of class tossing around the “bioball,” Evans’ version of an ice-breaker through “cool facts.” And when instructing evolutionary biology, she’ll hand out sheets of paper to her group and tell them to write in a Dear-Abby fashion to the Father of Natural Selection. She rightfully calls it “Dear Darwin.”

Among the other nine SI leaders is junior Clay Snyder, who just kicked off his second semester as an instructor of general psychology. A frequenter of a session might find themselves describing the psychology of B.F. Skinner or Wilhelm Wundt — “W.W.” — while Katy Perry plays in the background. Although Clay also sports a fun philosophy, he takes the job of supporting the students that take time to study with him seriously, and swears by the effectiveness of being backup for professors.

Overall, he hopes students don’t confuse the two.

“We’re not really lecturing, but pushing people in the right direction,” he said. “SI is meant to keep you on track, and on your study schedule. So when you have Biology and Psych tests in the same week, you’re able to manage and do well on both of them. I always tell my students, cramming is not conductive.”

And for some folks, neither is studying alone.

Formoso, who brought friend and medical technology major Randi Lyle to Evans’ session, said that for many like her, having others to keep her focused is something her empty dorm room doesn’t permit.

“When I study alone,” she said, “I just can seem to concentrate. After a while I’ll just be staring off around my room — so I just come here.”

Other than being the push in the right direction, Jain said that SI sessions are also worthy of other outcomes. Along with the study skills passed down from veteran SI leaders, and the “historically difficult” material made somewhat easier to understand, Jain said that one of most rewarding parts of an SI session is what happens afterwards.

“I’ve seen students form study groups outside of SI because they met each other in SI,” she said. “And now they’re friends.”

Formoso and Lyle, who plan to be at Evans’ next Biology session, both agreed that Evans rightfully attains her veteran title as an SI leader and that her review style was on par enough to bring them back. Yet for Lyle, group instruction with cellular biology isn’t just for making friends.

“I’m also like kind of a nerd,” she said. “I want to get an ‘A.”

Contact Mark Oprea at [email protected].