CNN — Steve Maller, a flight attendant for nearly 20 years, was one of the flight attendants on the Alaska Airlines flight 1282 when a door plug blew out.

With the plane at 16,000 feet, the air pressure in the cabin plunged. Clothing and phones ripped from terrified passengers and flew out through the gaping hole. Maller helped make sure passengers were safe and breathing oxygen during the plane’s harrowing descent. For his work under pressure, he and other flight attendants on board received praise and thanks from many of the airline’s top executives, including an email from Alaska CEO Ben Minicucci.

“He was very complementary of the crew for our actions,” he said.

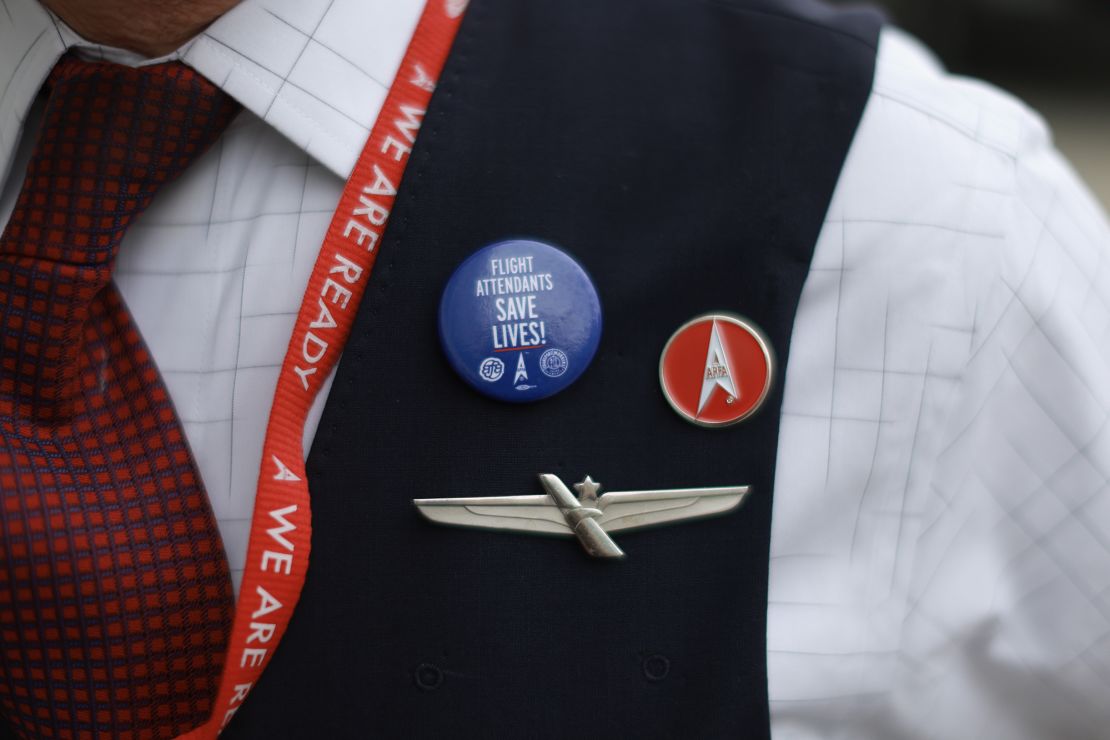

But Tuesday, Maller was on picket lines, along with thousands of other flight attendants from most of the nation’s major airlines, protesting for better pay.

“It’s kind of a strange juxtaposition,” Maller said recently about the upcoming picket plans. “I appreciate him reaching out. That’s great. But there’s more work to do.”

Maller said he can’t speak about details of the flight because of the ongoing investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board. But he did say he’s also proud of how the flight attendants on board responded.

“What 1282 reminds us, again, is the critical importance of flight attendants,” he said. “We don’t have these types of emergencies on a regular basis. But when they happen there’s no substitute for well-trained and qualified flight attendants [who are] willing to put their safety behind the safety of the people that they’re charged to take care of. And that’s what we all did.”

He said many flight attendants, particularly veteran flight attendants like himself, have seen very little increase in pay in the last several years as negotiations between the airline and union stretched on. He said most flight attendants he knows have a second job. He’s worked as a bar tender himself at times.

“You have to have something to have livable pay, to make ends meet,” he said.

“So it’s nice to have the support [of management] in the moment. But now it’s time to show support for all of us at Alaska Airlines,” said Maller, who is a union official at his airline’s Portland base. “The fact is that every flight attendant at Alaksa would have done the same thing on that flight. And management needs to recognize that value that we bring to the operation.”

Many haven’t received a raise in years

There are 75,000 flight attendants spread between four of the nation’s five largest airlines — American, United, Southwest and Alaska — who have gone a year or more since their previous labor contracts reached their negotiated end date.

But under the law that controls labor relations in the airline industries, union members don’t have the opportunity to simply go on strike, the way the autoworkers did at General Motors, Ford and Stellantis this past year when those contracts expired. Instead the law, which is known as the Railway Labor Act because it also controls rail workers’ labor relations, requires union members at airlines to remain on the job until after federal mediators declare an impasse in talks.

So the pickets by flight attendants across the country Tuesday doesn’t mean any of the airlines are on strike, or that a strike is imminent. And since the thousands of flight attendants who plan to be on the picket lines are off duty, their presence on the picket lines won’t disrupt Tuesday’s flight schedule.

But the fact that three different unions that represent nearly 100,000 flight attendants among them are all participating in the picketing is an unprecedented show of strength and unity by unions. The three flight attendant unions — the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA and the Transport Workers Union — have often competed with one another in the past more than they cooperated.

The APFA, which represents 23,000 members at American Airlines, is the first that has filed to have an impasse declared by mediators. Mediators will meet with the airline and the union about that request next month.

“Our goal is not to go on strike,” said Julie Hedrick, president of the APFA. “But we’re not going to settle for a contract that is less than we deserve. It’s very disheartening to the members. American is reporting record revenue. We know management is seeing it. But we’re not seeing it. We’re tired of waiting.”

Living in cars, preparing for strike

One of those American flight attendants is Ondrea Wallace, who has been with the airline for 10 years. She is one of those who works two jobs to pay the bills, working as a waitress at a New York restaurant between flights.

She said she’s already preparing for a possible strike, speaking to bosses at the restaurant about picking up extra shifts and to her landlord about possibly being late on rent. But she said the flight attendants have no choice but to push for better pay.

“We have flight attendants who live in cars because they can’t afford to live where they’re based,” she said.

Flight attendants say among the things that need to change is the hours they need to be at the airport, or on a plane during boarding and deplaning, for which they don’t get paid. For many, hourly pay basically begins when the plane’s door closes. While being a flight attendant is a full-time job, many flight attendants only get about 75 hours of hourly pay a month, Wallace said.

“We can work 15-16 hours a day but only get paid for seven hours,” she said.

The airlines have issued statements saying they support industry-leading contracts for their flight attendants. The airlines all agreed to deals in the last year with pilots’ unions that gave raises of 30% or more. American’s statement says it is offering boarding pay to its flight attendants. All the airlines say they’re confident they can reach a deal without the unions going on strike.

“We remain at the negotiating table, ready to make a deal — and we are confident that we will reach a new agreement soon,” said American’s statement.

“We agree with our flight attendants that we need a new contract, which is why we’ve been working hard to get an agreement,” Alaska’s statement said. “We remain optimistic in the negotiations process.”

Barriers to going on strike

Under the Railway Labor Act, even if such an impasse is declared at American or one of the other airlines, a 30-day cooling off period keeps the workers on the job. And at the end of that, President Joe Biden can name a federal panel to try to come up with a contract proposal both sides can agree to. While that happens, union members would need to stay on the job for another 60-day period. And at the end of that period, Congress could impose a contract on the union to block a strike, as it did when it blocked a rail strike in late 2022.

But the unions are on the record wanting the opportunity to go on strike without intervention by either the president or Congress.

“I do think Joe Biden will support a credible strike threat,” said Sara Nelson, president of the AFA-CWA, which represents nearly 50,000 flight attendants at 10 different airlines, including about 30,000 at United and Alaska who are working on old contracts.

She said if mediators start the clock ticking toward a possible strike at one or more airlines, and Biden does not name a federal panel to keep them on the job, it doesn’t necessarily mean a strike will happen.

“The airlines will cave long before that happens,” she said. “They know they’re going to have to pay. All these contracts are in a mature state of negotiations. Any one of them could be resolved in a matter of days.”

But Alaska Air 1282 flight attendant Maller said rank-and-file flight attendants are ready to strike if it comes to that. He said many are already walking out — and the steady flow of flight attendants leaving Alaska every month worries him.

“It was unheard of five years ago they would quit their jobs. Now we have 20, 25, 30 a month,” he said. “The flight attendants are unhappy. We’re frustrated with management. The longer they play games with us, there are consequences.”