The ‘landlord who cares’

April 21, 2019

Chris Myers’ feud with the city of Kent and Kent State may finally be over

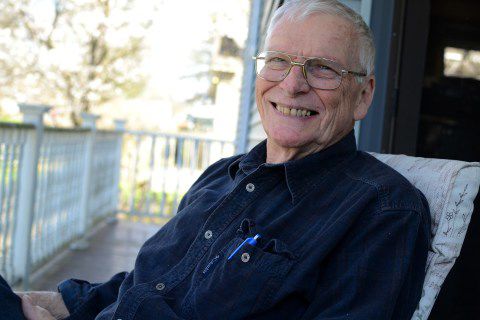

Within three minutes and nine seconds of meeting Christopher Myers, he interrupted me, and with a smug look on his wrinkled face and a coffee mug pulled to his lips, told me he was a controversial man.

Myers, a landlord in town since 1975, fought with the city of Kent and Kent State University beginning in 2012, when construction started for the Lester Lefton Esplanade and dust in the air began to settle on the shingles of the South Willow Street home he rented out to college students. He grew more agitated when the university began construction in November 2014 for the College of Architecture and Environmental Design, which is when he became “an instant environmental activist.”

He said his tenants couldn’t enjoy sitting on the front porch, and their cars were constantly covered in dust. “And worst of all, they had to breathe it!” he wrote to 70 people (city council members, university officials, local reporters and editors) in an April 2018 email.

Myers was angry — more than six years later, he still couldn’t let it go. And by protesting and maintaining his vocal role in the community, he made it his mission for everyone to know.

As Myers sat on the ivory couch in his living room in the fall of 2018, he donned large, square glasses on his face. He wore a red Cleveland Indians sweatshirt, cargo shorts, bandages around his knees, white socks pulled high past his ankles and slippers held together with lots of duct tape.

Myers was born in a house in Kent, the second house on the left at the entrance to Meredith Street. That was “82 freakin’ years ago,” and Myers said he spent a lifetime just being here — being a good citizen of the city, he meant.

Myers’ current home on East Elm Street in the heart of the city is blue like blue jays, and tall, orange flowers bloom along the path that leads up to his front porch. In a way, its old-timey exterior resembles a dollhouse. The 15-bedroom home Myers rented out to female-only tenants a few minutes away was his other baby, which he tended to obsessively, like a father who can’t get over his child growing up.

That house is now owned by the university’s Board of Trustees, which purchased it from Myers in March. The house was appraised at a value between $675,000 and $700,000.

Myers used to care for four rentals, but his knees are too weak for that now. He grew up here, attended school here, married and divorced here, raised his three kids here, served on city council here. For Myers, Kent is home. Kent is his city.

Covered in Dust

Kent State offered to buy Myers’ South Willow Street house when the Esplanade construction began. If Myers remembers correctly, the university bought and tore down about 13 homes along South Willow, Erie and Lincoln Streets. Whatever amount it offered wasn’t enough for Myers, though, and he refused to sell. But the commotion of loud bulldozers and banging hammers was an annoyance to him and his tenants and in the middle of the architecture building’s construction, about May 2015, Myers said the true “dust storm began.”

“Clouds of dust clogged my screens. My girls could barely use the front porch, the dust clouds were so thick,” he said with a can-you-believe-it look on his face.

“(The tenants) had to clean their cars off any time they wanted to go out to drive,” Myers says. “My girls had to go onto that construction site and hunt for somebody to move the truck — and the city didn’t give a damn.”

So Myers began to “rattle their cage” at city council meetings. He said he protested about once a week, and he was usually ready to go by 7 a.m. He still occasionally protests near the architecture building, usually close to the Starbucks at the corner of South Lincoln Street and East Main Street.

Myers’ sister Barbara, who lives in Austin, Texas, told me on the phone their parents raised them and their brother, Jay, to be “bright and capable” individuals. Chris — who she refers to as “Kit” — had a strong sense of right and wrong, she said, and that it’s his calling to speak out on the dust that once polluted his life.

“Anything he chooses to do, he does well,” Barbara said of her younger brother, and his protesting is no different.

“He just thought that no one seemed to care,” she said, remembering when the protests began, and she sounded sort of sad. “He feels he must get people’s attention, and he doesn’t know any other way to do it.”

Myers got up several times during my visit to rummage around upstairs for his hand-lettered protest signs. One is addressed to the “Kent see-no-evil quintet,” which includes Kent City Manager Dave Ruller, Mayor Jerry Fiala, members of city council, the police and health departments and the “air pollution quartet,” made up of Kent State President Beverly Warren, Associate Director of Architecture and Engineering Joseph Graham, Executive Director of Facilities, Planning and Operations Michael Bruder and former Associate Vice President for Facilities, Planning and Operations Thomas Euclide.

The third group on the sign is “the victims,” the 25 tenants who lived in his rental when all the construction was taking place. Another sign refers to the architecture building as “Hypocrisy Hall,” and reads, “A monument to Pres. Warren’s endangering the health of 25 students by violating air quality laws.”

In May 2016, the Akron Regional Air Quality Management District notified Gilbane Building Company and the university that they violated Ohio Administrative Code 3745-17-08, which restricts the emission of dust. There was no fine, and the university was advised to hose the streets to keep the dust down.

Eric Mansfield, Kent State’s executive director of university media relations, confirmed the university dealt with Myers for years.

In a 2016 KentWired article, Euclide said the university was willing to hear Myers out on his concerns. Kelvin Berry, Kent State’s director of economic development and community relations, echoed Euclide’s message, and added Myers declined several offers to meet with the university.

“He wants to protest, but he doesn’t really want to tell us what he wants. …If he really wants to get something done in terms of a relationship with the university, we’ve opened that up to sit down and talk because that’s how it starts,” Berry said.

“The university continues to work with Mr. Myers and all who live and work around our campuses as we are committed to being good neighbors and building strong local relationships,” Mansfield wrote in an email in Fall 2018.

These comments made me think the word “gadfly” was invented for Myers. He carried his grievances as he buzzed and bustled through town for as long as he could.

Last April, former Kent Clerk of Council Tara Grimm filed a complaint against Myers with the Kent Police Department. Grimm’s statement lists incidents and dates when Myers made her uncomfortable. For example, he “waited for me in stairwells and the parking lot after adjournment,” she said, “violated Council Standing Rules on numerous occasions” and his “verbal tirades escalate each time” were some of her complaints.

The statement doesn’t ask for any charges to be filed against Myers, but Law Director Hope Jones notified Myers by phone and via email “not to have any direct or indirect contact” with Grimm because “she does not feel safe around you.”

Myers was open about sharing Grimm’s statement with me, which he said “reads like a teenage girl trying to get a rival cheerleader in trouble,” then handed me a copy.

Myers, waving his arms, read off Grimm’s complaints.

“Phone harassment, unannounced office visit, picketing,” he said, squinting as he scanned the paper. He paused for a moment.

“Phone harassment,” he repeated, his voice growing louder. “Phone harassment?”

Myers leaned in and peered at me as he became more agitated about the accusations.

“Picketing. Picketing! Look here — this is just awful,” he said.

A quiet meow interrupted him. Myers opened the screen door for his black and white cat, who stepped inside, plopped his soft body near my feet and curled into a ball. I asked his name.

“My daughter calls him Boo, but I like to call him Stretch,” Myers said, “because when he lays down, he stretches out like this,” and he spread his arms wide like a child who asks how much you love them and needs to be shown.

Battling With His Words

Jones, the law director, told me over the phone she didn’t know Myers for long (she began her job in March 2018), but she was familiar with his history with the city over the years.

Jones said he brought up Grimm’s statement at council meetings, and she recalled a meeting last summer where he was “inappropriate and loud,” so much so that police escorted him out of the building. She added that it was her understanding Myers was cordial with the police, and perhaps his frustration swelled when he wasn’t allowed to speak longer than the council permitted.

In the same April 2018 email, where Myers called university and city administrators “polluteocrats,” he said Grimm’s statement was “really every activist’s dream” because it made for “incredible publicity for one’s cause.”

Myers sometimes nonchalantly referred to the council members as fascists. I asked him what he meant by this, what made them fascists.

“Fascism is my way or the highway. Fascism is intimidation. Fascism is false reports. And that’s what they’ve done,” he said about Grimm’s statement.

“If that isn’t fascism, I don’t know what fascism is,” he continued. “When you can take somebody for what they are saying, legally, and write an intimidating police report, you are indeed pretty close to fascism, and you gotta watch out for it.”

In May 2017, Myers attended a city council meeting and used the word “asinine” to describe a remark made by Councilman Garret Ferrara. Myers said Grimm called his language “vulgar,” a word recorded in the meeting minutes.

He didn’t like that. He said the members felt targeted by him and refused to have a dialogue, which he believed used to exist when he served on council from 1979 to 1983. Myers told me he fights his battles with words, never violence or threats.

I told him I, too, value words, and he veers off topic to speak on the growing library in his home. Myers had books stacked on shelves, books sitting on top of his speakers, books splayed across his living room floor. As I later pore over his emails to city council, I notice he finds space in his long rants to recommend books to members.

At a fall council meeting, Myers showed up with his Webster’s Dictionary in hand, and when his three minutes to address the council arrived, this is what he said happened:

“Mayor, I have my Webster’s Dictionary here, and on page 109 is the definition

of ‘asinine.’ Would you like to read it?” Myers asked.

“No, Chris, you read it,” Fiala told him.

“So anyway,” Myers went on, “I read it and I said, ‘I’m going to leave the dictionary here and you can all get together and make up a list of inappropriate words.’”

He left the book there on the table, stood up and went home. A smirk flitted across his face as he remembered that evening.

As Myers walked me down a stone path to my car, he asked if I liked his duct-taped slippers. We both sort of laughed. “Yeah, they’re great,” I answered, careful not to offend him.

I turned the ignition key, and Myers started to speak. I rolled down my window.

“You ever read ‘The Handmaid’s Tale?’” Myers asked.

I shook my head.

“There’s a line in there: ‘Don’t let the bastards grind you down,’” he said.

I half-smiled in all my awkwardness because I wasn’t sure what else to do.

“That’s what you’re doing, huh? Fighting for what you believe in?” I asked after a long pause.

“That’s right,” he said, nodding, “but let me be clear. This is all for my tenants. It’s always been about the tenants — I just got caught in the middle.”

But Myers relished the fight, and every confrontation was like adding fuel to a fire. He was controversial. And he loved it.

Now that the South Willow Street house is off his hands, he said it’s time for a change. “I thought I would miss 224, but I don’t,” he said in a recent email. “After forty-four years it was time to duck and do some earthly traveling before I complete my journey between the eternities.”

He signed the email: “Cheers! Just call me Christopher M. Myers, retired.”

Valerie Royzman is the editor-in-chief. Contact her at [email protected].