Opinion: What society needs to learn the most

April 30, 2017

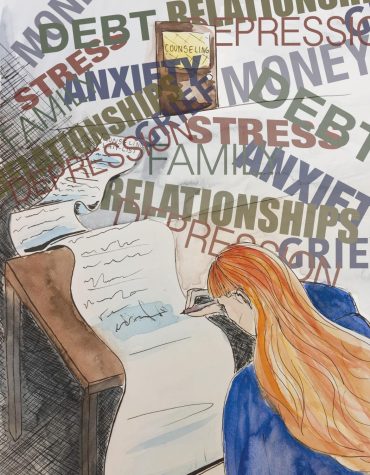

Anxiety isn’t just excessive worrying, and it’s not easily described as it appears in pieces titled something like “Top 10 Things People with Anxiety Want You to Know.” Neither is depression or any other internal struggle.

Mental disorders are never that simple, and they’re never the same for everyone.

I can only tell my story.

I have been labeled as a gifted student since preschool. While this may seem like an honor, it only added more pressure and stress. Getting less than an “A” was never an option, especially as I followed in my genius brothers’ footsteps. When I transferred schools in eighth grade, I was relieved because no one knew my family — there were no expectations.

Unfortunately, my classmates caught on as I ruined test curves, won awards and qualified for advanced courses.

Socializing was never an issue for me; I lived next door to a same-aged girl generous enough to introduce me to her friends and treat me like I had known her since birth.

In high school, I was elected class president both junior and senior year, National Honor Society president and named co-valedictorian with my best friend. At the end of the year, I was voted “Most Likely to Succeed.”

Impressive, right?

I established a great name for myself on paper, so no one even saw me start to self-destruct.

Junior year of high school, I developed a lot of stomach issues. Within a few months, I lost 10-15 pounds on my short, 5-foot frame, which was weight I desperately needed to stay healthy.

I couldn’t eat most foods, and if I did eat, the food didn’t stay down for long. I missed both final exam days of the second trimester because of what was suspected to be the flu.

Throughout my senior year, I underwent many diagnostic tests to try to find what was causing my major weight changes and stomach pains. I was put on medication to take before and after I ate in the hopes that I could gain back some weight. Nothing helped.

I ended high school in the hospital emergency room the night before the graduation ceremony, suffering from dehydration (I couldn’t even keep liquids down).

The next day, I weakly gave my speeches and talked with the guests at my graduation party.

I had been to multiple doctors and specialists to give me a physical diagnosis before they all gave up on me. The best answer I got was that my stomach was inflamed.

Still struggling, I prepared to move across the state for college.

I was lucky entering college: I made great friends with my roommate and established relationships with my professors. My stomach started to feel better, but my mental state got worse. I felt hopeless and empty, as if my friends hated me and as if I didn’t want to be anywhere: not school, not home.

Not anywhere.

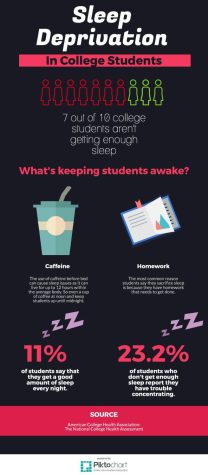

I stopped sleeping. My roommate and I drifted apart. I can’t blame her; I was impossible to deal with. I was never happy and never gave her any indication of how to help me.

Spring break ended in the second semester, and I completely broke down at my extended family Easter. For the first time, I was telling myself that I could not get through the rest of the year.

My breakdown alerted my family, and they kept a close eye on me, constantly calling me to assure that I had not done anything impulsive and destructive.

I got through my freshman year and finally admitted to my family doctor my intrusive and depressive thoughts, the never-ending worries and the sleepless nights.

I was put on several medications at once, and I was finally sleeping again. The medicine I was on caused me to sleep most of my summer away and experience unfortunate side effects.

Since then, I have switched dosages and medications several times, but I have not found a consistently effective treatment. I’m currently on two daily medications: an antidepressant and a sleep aid.

I’m not embarrassed to admit it: The medication helps me get out of bed and function somewhat normally.

For those days where I can’t handle the pressure, I have a fast-acting medicine for my anxiety attacks.

These attacks make me feel helpless and hopeless. I completely break down. I’m numb. I can’t even accurately describe the heartache and exhaustion I experience.

Even with the medication, I take a few days to recover and spend most of my time in bed. But I keep fighting for a “normal” life.

The worst thing that anyone can say to me is, “you can’t handle that with your anxiety.” I can handle responsibility, and I can still succeed. I just need more support as I struggle more than the average person. Not all of my friends understand that, and that is what I struggle to accept: that no one truly understands.

I know I sound like a girl who just couldn’t handle the pressure, who couldn’t accept the great life she was given.

And that’s why mental disorders suck.

I will never be able to explain why I fell apart or continue to put my pieces back together — I can only explain how I have struggled.

This is my story, and I don’t expect anyone to understand. I don’t want pity, I just need support.

Everyone needs help fighting their own mental disorder, and that is what our society needs to learn most.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a student media project entitled “The Silent Struggle.” See the whole project here.

Nadine Klemine is a guest columnist and junior psychology major, contact her at [email protected].