A sound, fundamental relationship

October 20, 2016

On a muggy, late August evening in 2013, Mike Lude sat next to his friend and former colleague, Don James, during the University of Washington’s season opener against Boise State in the newly remodeled Husky Stadium, watching head coach Steve Sarkisian lead UW to a 32 point win over the No. 19 team in the nation.

Two decades earlier, James was the one roaming the sidelines of the historic field that borders Lake Washington and overlooks the scenic Cascade Mountains.

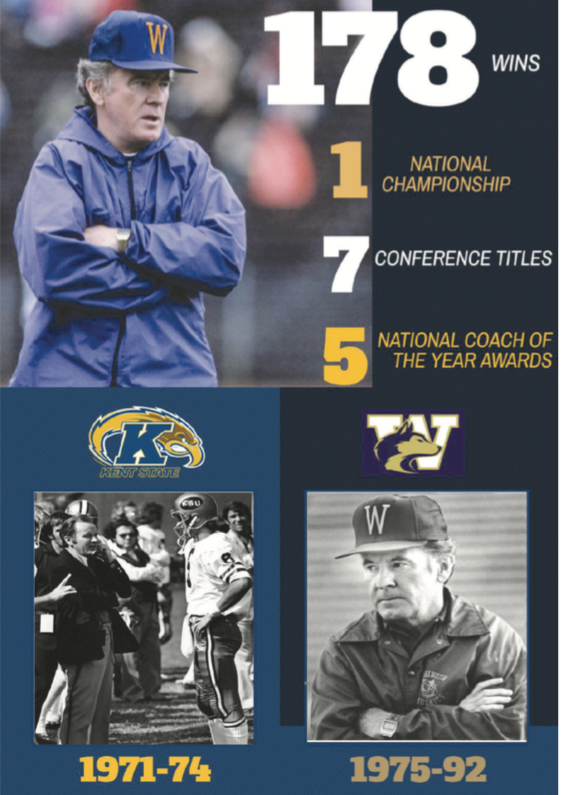

Whenever he was first hired in 1975, most had wondered why Washington took a chance on a guy whose only other head coaching job had been at Kent State.

But in his 18 seasons in Seattle, James took the Huskies from a middle-of-the-road Pac-10 team to a national contender.

There were the six trips to the Rose Bowl, four of which he won. There were the six conference titles. And then there were the five national Coach of the Year awards.

He was “The Dawgfather” of Washington football and remained connected to the program long after retiring in 1993.

He served on the committee that proposed the $280 million redesign of the 93-year-old venue and he gave his annual preseason pep talk to the team one week before the start of the season.

But on this day, James was simply supporting the school that had meant so much to him over the past 38 years with his family and longtime coworker.

Midway through the game, his wife, Carol, informed Lude that James hadn’t been feeling well that morning.

When probed about it, though, the tenacious coach claimed he was fine.

However, James wasn’t one to complain about anything. He had an innate toughness about him that was born on the gridiron of Massillon High School in the late 1940s, bred while playing for the University of Miami and refined as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

“Now don’t BS me. Are you alright?” Lude asked his friend.

“Mike, I’m okay,” he replied.

Laying the groundwork

Inconsistency plagued Lude’s coaching career at Colorado State. There was the 0-10 mark the Rams posted in 1962 – his first season in Fort Collins after spending the previous 10 at the University of Delaware, where he is credited with co-developing the Wing-T offense.

There was the 1966 team that knocked off No. 10 Wyoming en route to a 7-3 record, his only winning season. And then there was the 0-4 league mark three years later that garnered a last place finish in the Western Athletic Conference and his ultimate release.

Shortly after getting fired from Colorado State, Lude was hired by the Denver Broncos to scout college players during spring practice and was subsequently sent to the College of William & Mary, a Southern Conference program led by college football hall of famer Lou Holtz.

“Mike, you ought to apply for the job at my alma mater, Kent State,” Holtz told him.

“Lou, I don’t even know where Kent State is,” he responded. “I know it’s in Ohio and I believe it’s near the turnpike.”

Holtz’s recommendation wasn’t even enough to make Lude entertain the offer. He had been a football coach for the past 22 years since graduating from Hillsdale College, a small liberal arts institution in lower-Michigan, so why would he want to begin a career in athletic administration?

But three days later, when he was at the University of Virginia to observe a practice, his attitude began to shift after Steve Sebo, UVA’s athletic director at the time, convinced him to apply anyway.

So, with nothing to lose, he mailed Kent State his resume, never fully expecting to receive a call from the school’s president.

A month later, in early May, after scouting the University of Iowa, Lude was having dinner with head coach Ray Nagel and his wife at their home in Iowa City.

He wasn’t fully aware of the events that had unfolded earlier in the day until he turned on the television at his hotel room and saw a news bulletin that said that the Ohio National Guard had discharged its weapons on Kent State’s campus, leaving four dead and nine wounded.

In that instant, Lude told himself that if anyone from Kent State ever called him about the job, he would decline without hesitating.

Once spring practices ended at the conclusion of the academic year, he returned to Colorado looking for work and eventually landed a position as an agent for Moore Real Estate Services, the state’s second largest firm at the time.

Dax Moore, the company’s founder, had sponsored a weekly CSU coaches T.V. program all eight years Lude was a head coach and told him that he had an opening if he was interested.

It wasn’t necessarily what Lude wanted to do, but it was steady work, nonetheless.

However, eventually, it grew boring, something so mundane that he couldn’t envision himself continually doing it for an extended period of time.

So, in early July, when Kent State’s faculty representative phoned Lude asking for an interview, he obliged, viewing it as a quick exit from the real estate industry.

If anything, he thought, this was an opportunity to get back into the realm of college athletics, even if it wasn’t as a coach.

In late October – when Lude returned home from his job at Moore Realty – his wife, Rena, told him that the president of Kent State, Dr. Robert L. White, had left a message wanting him to return his call. Almost immediately, Lude phoned White, who quickly informed him that the job was his if he wanted it.

“Mike, we have made so many mistakes in intercollegiate athletics for 25 years. All I want you to do is fix it,” he said. “There’s no office, there’s no staff. There’s nothing.”

Finding a replacement

After the seventh game of the 1970 season, Dave Puddington grabbed the tan, 8×11 in. manila envelope that he had previously sealed and made his way to the University Inn on South Water St. where Lude was temporarily staying.

Upon seeing Puddington at his door, Lude instantly knew the reason for his visit. When he first became Kent State’s athletic director, Puddington approached him about resigning from his post as the university’s head football coach, citing “the prevailing contagious negativism on campus and in the community” that resulted from May 4 as the main reason.

Though it was almost than seven months post-tragedy and even though Kent State was finally beginning to pull itself back together after the shooting, Puddington wanted an out. And starting the campaign with a 2-5 record was the last straw.

He wasn’t the only one who was having difficulty rebranding Kent State athletics. Despite the fact that he was able to relate to Puddington’s situation, Lude realized that change would have to eventually ensue if he wanted to establish himself as a worthy athletic director.

But he also knew that he didn’t have time to search for Puddington’s replacement midway through the season

“David, I don’t want that envelope,” he said. “I got too many problems.”

Prior to Lude’s arrival, Dr. Carl Erickson – head of the division of health and physical education – oversaw the university’s athletic programs and juggled teaching responsibilities with the administrative duties that came with fielding eight varsity teams.

Lacking a work space inside the Memorial and Athletic Convocation Center, White suggested that Lude occupy the empty room across the hall from the president’s office in the administrative building. It wasn’t necessarily an ideal situation, he thought, since White could constantly monitor his progress, but as time wore on, he grew accustomed to it.

If anything, it helped inflate his nonexistent reputation as an athletic director since word spread throughout campus that he must have been overqualified if White wanted him in the office next to his.

He then appointed an assistant athletic director, sports information director and business and ticketing manager in an effort to bridge the gap between the local Northeast Ohio communities and the university in terms of fan support.

Once that was done, he had to figure out what to do with Puddington.

But after losing, 20-8, to Miami (OH) on Nov. 14, the head coach once again returned to Lude’s room at the University Inn, envelope in hand.

And this time, he accepted the letter of resignation – effective after the season’s final game against Xavier – because he had a handwritten note with the names of the top six coaches he wanted to interview on a folded sheet of paper stashed in his shirt pocket.

Besides, topping the list was Don James, the University of Colorado’s defensive coordinator.

James, who had grown up in nearby Massillon and played high school football for Chuck Mather, had connections in Ohio and therefore could easily recruit the state.

He had extensive experience playing and coaching in the south against Atlantic Coast and Southeastern Conference teams during his time as both a quarterback and defensive back for Miami. He was a graduate assistant on Mather’s staff at Kansas from 1956-57.

He had spent six years as the defensive backs coach and defensive coordinator at Florida State. And he had worked under legendary coach Bump Elliot at Michigan.

But what really stood out to Lude was the fact that James had always been a defensive-minded coach by trade.

Although Lude had originally planned to call James the next afternoon to see if he would be interested in landing first head coaching position, James phoned him first, bluntly stating his intention.

“Mike, I’d be interested in that job,” he said.

“Get your briefcase together,” Lude replied. “Put a couple of clean shirts in it and there will be a ticket for you at Denver Airport to fly out to Cleveland to come and see me.”

Sound, fundamental coaching

Don James was a football mastermind, the man who had every second of a practice accounted for, from the length of water breaks to the precise duration of the weekly intersquad scrimmages.

His philosophy was simple, though, one that emphasized the importance of diligence and continually stressed the need for organization within the program. It was a mix of good old-fashioned hard work and sound, fundamental coaching.

“What I remember, specifically, is how different the two coaches were. Coach James was very disciplined, very organized,” said Ted Bowersox, a quarterback who played for both Puddington and James after being recruited out of Canton McKinley High School in 1968. “He had a very methodical way about coaching.”

Entering James’ first year at Kent State, the NCAA extended the regular season to 11 games. With an additional week on the schedule, Lude contacted Earle Edwards, North Carolina State’s head coach, with a simple proposal.

NC State, an Atlantic Coast Conference program, needed an easy win, a guarantee game to pad its schedule for the rankings. Kent State, on the other hand, simply needed a large payout from an established program to fund its athletic department.

So, naturally, getting Edwards and NC State’s athletic director to agree to schedule a MAC team that hadn’t posted a winning record in six years wasn’t too much of a challenge. The real test, however, was how James was going to transform a program that went 3-7 the year before into a conference contender.

His head coaching debut against the Wolfpack ended with a 23-21 win, which promoted Edwards to tell Lude, “Friendship is fine, but don’ ever call me again for a favor.”

But the next five games of the 1971 season resulted in five consecutive losses by an average of 17 points.

James’ first season at Kent State wasn’t ideal, but the flashes of resiliency – the NC State upset, an 11 point victory over Xavier and shutting out Marshall – were indicators of what could potentially happen with his nucleus of talent.

And the following season, when the NCAA ruled that freshman were eligible to play for the varsity team, everything seemed to come together.

Now, James and his young staff of coaches – many of whom were only years removed from being graduate assistants – were able to play their freshman immediately without a waiting period, which meant that the team he fielded was a mix of both his players and those who were recruited by Puddington.

Even though the 1972 season began with a tie against Akron and a 34 point loss to Louisville, Kent State managed to win four of its five league contests to clinch the conference title, the first and only in school history, which led to a berth in the Tangerine Bowl.

“Coach James coached from a tower and it was like he was watching all the time. You didn’t want to let him down, therefore you put forth whatever effort it was,” said Handy Lampley, who played for Kent State from 1968-71. “But at the same time he was a down-to-earth guy …”

The longer James was at Kent State, the more wins the program accumulated.

In 1973, the Golden Flashes went 9-2 and narrowly missed out on another league title after a late season loss to Miami (OH). And the following year saw an upset win at Syracuse and a 7-4 finish.

Lude realized he wouldn’t be able to keep James much longer. Mid-major schools were constantly being used as stepping stones to get coaches into power conference programs and Kent State wasn’t any different.

What he didn’t know, however, was when he would be receiving that phone call.

Settling in Seattle

Joe Kearney needed a new football coach and he knew exactly who he wanted. Having seen the success that James put together at Kent State, Kearney – the University of Washington’s athletic director from 1969-76 – recognized that he would be a perfect replacement to fill the void that was left after Jim Owens resigned in 1974.

Every time Kearney saw Lude, he would constantly joke that James would be the ideal candidate to replace Owens. But every time he asked Lude if he could interview James for the vacancy, he always responded with a simple “Absolutely not.”

Setting the working relationship aside, however, Lude saw this as a major advancement in James’ coaching career. He could always hire another coach, but James wouldn’t always have the opportunity to guide a power program.

Kent State had served its purpose for James. It gave him his first opportunity as a head coach and enabled him to cultivate his system at a mid-major level.

As a result, when Kearney approached James with a base salary of $50,000 per year with an additional radio-television pact valued at $12,500, Lude realized he couldn’t compete with those numbers. It was more than double the $25,000 James was earning at Kent State.

“I have never campaigned for other jobs since I have been at Kent. But I felt if anybody offered more money and security for my family, I would think about it,” James told The Daily Kent Stater shortly after being hired by UW in January 1975. “I’m very impressed with the people and opportunities in Seattle. The job is one of the top ones in the country and in one of the top major conferences.”

Searching for his second head coach in four years, Lude promoted defensive coordinator Denny Fitzgerald, who strung together a 4-7 season in 1975.

But James hadn’t forgotten his old boss back at Kent State and the initial opportunity he gave him as a 36-year-old first time head coach.

Two years later, when Kearney left to take over the athletic department at Michigan State, Washington President John R. Hogness and Dave Cohn – head of UW’s Tyee Board of athletic boosters – asked James if he could endorse anyone for job.

“I want to recommend my old boss back at Kent State,” he told them.

Bowing down to “The Dawgfather”

On a cloudy, late Oct. morning three years ago, a purple flag adorned with the initials “DJ” in gold lettering was hoisted atop Seattle’s iconic Space Needle, freely flapping 605 feet above the city’.

Later that evening, after the first 30 minutes of play in Washington’s Pac-12 contest against California, members of the Husky Marching Band – positioned at opposite sidelines – began its halftime show by converging upon a pair of temporary “DJ” logos embedded at each 25 yard and playing Earth Wind & Fire’s 1975 hit “Shining Star.”

Ordinarily, halftime performances are utilized as a time when fans visit the concession stand, restroom or team store.

But even before public address announcer Eric Radovich informed the crowd of 66,328 of this performance’s significance, most remained fixed in their seats since it was their last opportunity to bow down to “The Dawgfather.”

Two days after attending the season opener against Boise State, James once again woke up feeling sick, but advised Carol not to call paramedics.

However, despite his objection, she swiftly dialed 911 so she could find out exactly what was wrong with her husband of 61 years.

After a full day of testing, doctors noticed that James had a malignant tumor on his pancreas and he began receiving chemotherapy to combat the issue shortly thereafter.

But the treatment wasn’t effective and his condition progressively worsened with each passing week.

Realizing that his time was limited, James began planning his own funeral the same way he approached his weekly game plan as a coach, methodically calculating exactly what needed to be done.

Four days before his death from pancreatic cancer at the age of 80 on Oct. 20, 2013, James auditioned musicians inside his Kirkland, Wash. home to play at his memorial service, one which he didn’t anticipate would run longer than an hour if each speaker was limited to three minutes

But a three minute eulogy wasn’t nearly enough for Lude. How could he touch upon 45 years of friendship in only three minutes, he thought?

So, he went over his designated timeframe, just like nearly everyone else who took the stage inside Washington’s Alaska Airlines Arena on that gloomy Sunday afternoon.

“He was the most organized and disciplined and attention to detail coach that I’ve ever been around,” said Skip Hall, who worked under James for nearly two decades at three different schools. “He was my mentor without question for all those years …”

Though he wasn’t in attendance, Alabama’s Nick Saban recorded a video tribute to the man who gave him his first coaching experience as a student assistant in 1972.

Former Missouri head coach Gary Pinkel, who was a tight end for James at Kent State and later served on his staff at UW, gave a speech remembering the impact he had on his career.

Following the 1991 season, Lude left UW to become the athletic director at Auburn, a position he held for two years before ultimately retiring.

James coached two more years before stepping down in 1993 in protest of a scholarship reduction and two-year bowl ban that the Pac-10 enforced because former players were found to have received payments from boosters.

But despite going their separate ways, Lude and James always remained close, both personally and professionally.

What started with a simple phone call inquiring about Kent State’s head coaching position ended with a Rose Bowl victory over Michigan that gave the Huskies a share of the 1991 national championship.

They had helped Kent State rebrand itself in the wake of tragedy. And they were responsible for the most successful run in the history of Washington athletics.

But more importantly, they had seen their working relationship blossom into a lifelong bond.

“Don James and I worked together almost 20 years and never had a fight,” Lude, now 94, fondly recalled. “We had the best relationship.”

Nick Buzzelli is a sports reporter. Contact him at [email protected].