Founder of Institute for African American Affairs dies; revolutionized Black students’ education

February 19, 2021

Edward Crosby, who empowered Black students’ education as the founder of Kent State’s Institute for African American Affairs, died Feb. 10. He was 88 years old.

Crosby led the Department of Pan-African Studies for 25 years, which replaced the institute in 1976, from 1969 until he retired in 1994.

“He was dedicated to the students and improving the life of Black folk in general. He did that his whole life,” said his son, Darryl Crosby. “Even after he retired, he started his own elementary school with the same idea in mind.”

Crosby co-founded the Ida B. Wells Community Academy in 1999 for Akron urban youth, which later closed in 2006.

He lived in the projects of Cleveland and was an A student during his elementary years at St. Edward Catholic School, but when he entered junior high school his behavior and his grades changed.

After a few troubling high school years, he graduated in 1951. That same year he went with a friend to visit Kent State.

“That trip changed my life,” he wrote in his biography on the department’s website. He proceeded to enroll and become a student at Kent.

In 1952, Crosby was drafted into the Army during the Korean War and served in England.

After he was discharged from the military, he returned to Kent State to continue his education which was paused when he was drafted. Crosby finished his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1957 and his master’s in 1959, both in German.

He received his Ph.D. in Medieval German Languages from the University of Kansas in 1965 and taught higher education in Alabama and Illinois from about 1965 until 1969, according to Crosby’s biography.

Shortly after that, his life took another turn when a former Kent State classmate asked him to return to Kent to form the black studies program that BUS had asked the university to establish.

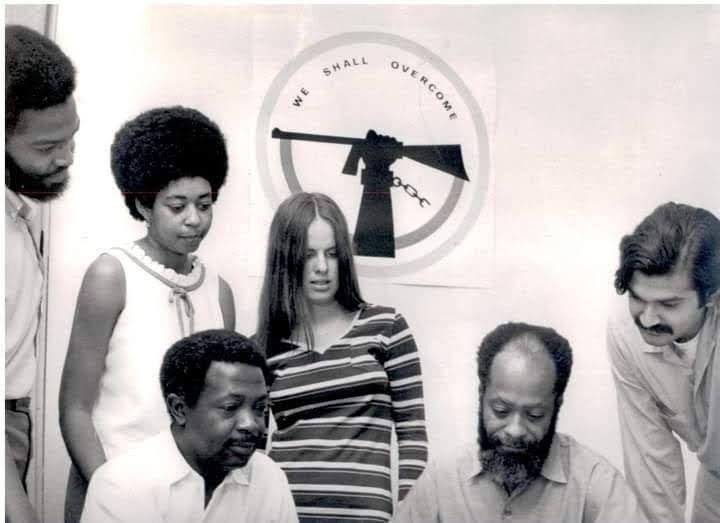

“When I came back in 1969, at the behest of black students, it wasn’t just to establish the Institute for African American Affairs. It was also to create change … and that’s just what I proceeded to do,” he wrote on the department’s website.

When he began his work in the late ’60s, people were not used to the idea of Black studies nor did they recognize that Black people had a history, Darryl Crosby said.

In February 1970, Crosby was one of the main organizers of the first celebration of Black History Month in the U.S. It was officially recognized six years later when President Gerald Ford announced its annual observance.

Crosby empowered Black students in their education and taught them about their history, Darryl Crosby said.

“He helped students if they had issues, like paying people’s rent on occasion. … [He] tried to get them through school and get their lives going in a certain way and have a knowledge of self and a knowledge of our history,” Darryl Crosby said.

One of Crosby’s former students, Mwatabu Okantah, who is now an associate professor and assistant chairperson in the Pan-African studies department, said he began his teaching career because of Crosby’s influence.

“I graduated in 1976, had no job and didn’t know what I was going to do. I got a job as a graduate assistant [at Kent State],” Okantah said. “Dr. Crosby put me in the classroom teaching a course called the Black Writers Workshop, and I had been a student in that very class. … It was Dr. Crosby who saw this in me before I saw it in myself.”

The department’s annual freshman picnic began in the 1970s at Crosby’s home. He brought Black students and faculty members together for a cookout to create community within the department.

As a student, Okantah was part of those cookouts.

“He gave us an opportunity to know him as a person. He was a father figure [and] a mentor for us. It also allowed us to interact with the staff. They understood that education didn’t just take place in the classroom,” Okantah said.

Described as an intelligent, driven and curious man by his son, Crosby began his work by the request of the students, and he focused on their success throughout his life.

“He had a life of service, even though he was employed by Kent. Everything in his life was about creating and educating and working with people,” Darryl Crosby said. “There wasn’t a separation between his job and the community.”

Edward Crosby is survived by his wife Shirley Crosby, sons Kofi Khemet, Darryl Crosby, Elliott Crosby and five grandchildren.

Because of COVID-19, services will be livestreamed from Sommerville Funeral Home in Akron Saturday at 10 a.m. An in-person private ceremony will be by invitation only.

Kelly Krabill covers administration. Contact her at [email protected].