Opinion: When art reflects a sobering reality

November 1, 2015

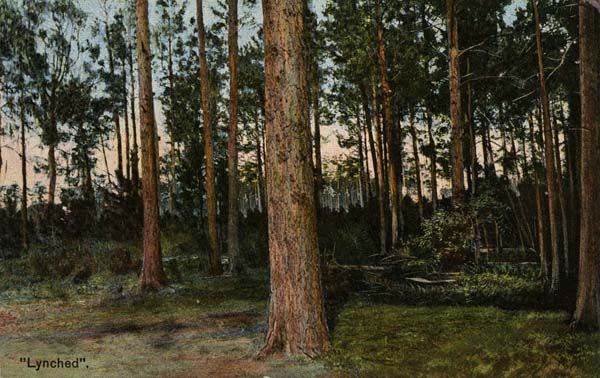

In a sea of flashing images that continuously force us to watch the brutalization of black and brown bodies, the calming quiet of Ken Gonzales Day’s 2015 work titled “Lynched,” only begins to become unsettling when we, as an audience, begin to fill in what isn’t there. His work is unsettling, challenging and absolutely heartbreaking.

In 2015, many Americans are still grappling with acknowledging racism and racial violence. Just last week a young girl was violently pulled from her chair and body slammed against the floor by an officer for being noncompliant in class. Despite the irrefutable evidence of excessive force, there are still many apologists who not only believe the officer was within his rights, but that this young girl got what she deserved.

Allow me to jump for a moment to the case of Eric Garner, who was illegally choked to death amidst several witnesses for the “crime” of allegedly selling illegal cigarettes. The Tuskegee Institute defined when murder becomes a lynching back in 1959: “There must be legal evidence that a person was killed. That person must have met death illegally. A group of three or more persons must have participated in the killing. The group must have acted under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition.”

When taken into account simultaneously—the video, the number of officers and the means in which force was applied—it becomes disturbingly clear that a modern day lynching may have occurred.

Gonzales-Day’s work not only shifts the emphasis from victim to perpetrator, but also confronts viewers with an often forgotten and rarely acknowledged history of racial violence against Latino bodies.

“I believe in art,” Gonzales-Day said to Latin Times, in reference to the Photoshopped images from “Erased Lynching,” in which the victims are subtly erased. “The erased images serve as a metaphor for the erasure of history. In his art exhibit, he didn’t want to re-represent and re-victimize Latino bodies. We should be able to have this conversation with me ‘showing you the body.’ People want to look at the body, get grossed out by the body, and then forget about it.”

Too often apologists use victim-blaming language to justify the outcomes of each violent encounter with police. Using actual postcards depicting the brutalization of Latinos in the West, Gonzales-Day’s series, “Erased Lynching” confronts viewers with an image that only leaves the perpetrators staring blankly out at us.

Back then, the agents of violence were self-appointed vigilantes “upholding rough justice.” Though centuries apart, these histories are intimately linked to the current forms of state violence inflicted on black and brown bodies.

Amanda Anastasia Paniagua is an opinion writer for The Kent Stater. Contact her at [email protected].