Defining the black experience

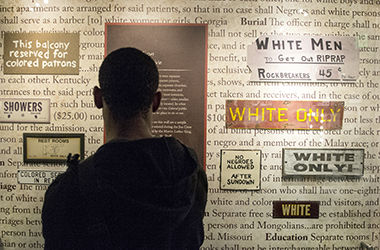

Kenny Jenkins, a communication Studies major, stops to look at a wall in the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia that shows just a small sample of the thousands of Segregation laws from the Jim Crow Era on Friday, Sept 19, 2014. The list of laws was compiled by the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic site interpretive staff.

September 21, 2014

At a Chinese restaurant in Big Rapids, Michigan, a group of Kent State students discussed the meaning of “the black experience.”

Their waiter, who asked them questions about race and race relations, suggested making a Facebook page about it.

“That’s a terrible idea,” said Jasmin Sparkman, a sophomore journalism major. “Because not only do you open it up for ignorant people to get on there and spout nonsense, but how are you going to try to tell or educate a race on how to approach another culture?”

“And talk about the black experience, how it is to be a black person,” interrupted Sabrina Mazyck, a senior political science major. “But not everyone has the same experience.”

Roughly 30 Kent State students in the Black Images I class traveled to Michigan Sept. 19 and 20 to learn about racism and how African-American culture was shaped throughout history. The class visited three museums: The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids; the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit; and the Motown Museum, also in Detroit.

“It’s a journey. It takes students through a journey,” said Traci Easley Williams, associate professor of Pan-African studies and journalism, who also teaches the class. “From the time you guys got on the bus to the time when you got off, it’s about the journey.”

Jim Crow Museum

A lynching tree, its grey bark gleaming in a spotlight, stood prominently in the middle of the silent exhibit room. Gathered under a noose dangling from the branches, the students watched, grimacing and scowling at times, as video clips and still photos of lynchings — or hangings — scrolled across the screen.

Once the symbol of death for blacks in the 1950s southern United States, the tree reminded students of a painful history. Images of white men posing with dead black men flashed on the wall as gasps and sniffles echoed throughout the otherwise silent room.

Lisa Kemmis, the museum assistant and tour guide, had prepared the students before they entered the exhibits by warning them about the racist content of the museum. Some weren’t prepared for the harsh realities the museum exposed.

“The museum is an experience,” Kemmis said. “It’s going to make you uncomfortable. It’s going to piss you off. It’s going to be painful. The museum is very a real experience.”

Divided into different sections, the museum includes exhibits on the Civil Rights movement successes (including a pen that was used to sign the Civil Rights Law of 1964), black musicians and athletes, military heroes, a wall of mammy dolls, Aunt Jemima figurines, a whole wall of the caricatures of black children and a section on the Ku Klux Klan.

David Pilgrim, the museum curator and director, said the goal of the museum is to change the way people talk about race relations by using items of intolerance to teach tolerance.

“I truly believe that you have to do an honest assessment of the past if you’re going to function intelligently in the present,” Pilgrim said. “This museum unashamedly and unabashedly deals with something in a way that no other place does that I know of, and that is, it’s not a black history museum, it’s not an American history museum, as those terms are understood. It is a racist museum. And by that I mean this: The objects in here are designed to get us to talk about racism and race relations. I will make no apologies for that.”

Students wandered the museum, some slower than others, quietly observing little details of each object set upon the shelves and within cases, and often made exclamations to classmates.

Isaac Floyd, a sophomore exercise science major, noticed a roll of toilet paper, with President Barack Obama’s face on it. Situated on a small shelf next to other recent examples of racist items, like the Ghettopoly board game, Chief Wahoo bobble heads, fake, copper-plated teeth and magazine covers featuring LeBron James as a “savage” character, the toilet paper stood out to Floyd.

“You can buy that at Spencer’s,” he said. “I could go buy that tomorrow. That’s crazy. I never thought about that.”

While looking at a Tuskegee Airmen GI Joe action figure, Jasmine Vaughan, sophomore criminology and justice studies major, said that she had a doll like that at home. Her mom collects them, she said, but she never expected to find one in a museum of racist memorabilia.

Students gasped at an animated video with stereotyped caricatures of black children as alligator bait and uneducated black men as sharecroppers in the cotton fields, produced by studios like Walt Disney and MGM. Some couldn’t believe that films like that could have been made at all, let alone circulated to the public.

“This was for kids!” exclaimed Dion McAllister, junior exercise science major. Racism, she said, is being systematically and subtly taught to children of all ages and all ethnicities through an innocent medium like television. And not only that, but it’s still present in today’s society with shows like “Family Guy” and “The Boondocks.”

Karess Gilcrease, a sophomore psychology major, looked at the Oreo Barbie, set among halloween masks of black caricatures, comic books featuring “savages” and candy dispensers of “negroes,” and was appalled.

Oreo Barbie, she said, embodies the concept of being black on the outside and white on the inside, a powerful representation of racism in something perceived as innocent.

“I’ve been called Oreo before. Or you get, ‘She talks white, she acts white, she’s oreo.’ That’s what other black students call other black students if they think they are acting white, which is talking with proper English, or getting good grades, or trying to do something to better yourself. It’s, ‘You’re an oreo,’” Gilcrease said. “That’s what the whole thing is for me.”

Even the year — 1997 — stuck with her. In the whole scope of African American history, 17 years is not a long time, she said. Knowing that at some point the creators of the doll discussed the Barbie, had it mass produced, then marketed it to a young audience disgusted her.

“The Jim Crow museum was powerful because it’s all still being made, and it’s being produced because people are still buying it,” Gilcrease said. “People don’t realize what that stuff means to people.”

An exhibit with three Ku Klux Klan figures stood next to the lynching tree. The figures, clad in the pointed white cloaks and red KKK symbols, visibly affected some of the students.

“I cried when I saw the wax statue of the KKK members,” said junior electronic media major Kenny Jenkins. “It just scared me. Because it was realistic, and thinking about it, like, if he was actually there, what he would have or could have done to me, or what he would have wanted to do to me. It was a painful thought.”

During the lynching video, some of the students noticed the children, young white girls, who participated or were exposed to the beatings in the film. This made some students question the current generation and what is being taught, both in school and society.

Key conversations should be with young people, students agreed. For younger generations, racism is perceived not to be real, but its almost omnipresent in subtle ways. From being asked how food stamps work to how to twerk in public, black students agreed that racism still exists in their own lives and on Kent State’s majority white campus.

“I felt so small,” said Kyndal Wilson, a student in the class, about coming to Kent State from a majority black neighborhood in Cleveland.

For Wilson, it wasn’t a violent reaction to her skin color, but subtle things that gave her a kind of culture shock that angered her.

Anger, Pilgrim and Kemmis told the students, is expected as people walk the exhibit.

“Anger is a necessary step, but it cannot be the destination,” Pilgrim said.

Kemmis, who identified as being in the minority as a white woman, said she often channels the anger she feels into constructive conversations.

“I’m here everyday,” Kemmis said. “I handle the collection. I do the research. I see some of the worst shit that humans do to each other that you could ever imagine. I’ve watched (the video) a thousand times. But at the end of the day, you cannot let that sit inside of you. Because it will eat you.”

Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History

After an emotionally exhausting day at the Jim Crow Museum, students boarded the bus early the next morning and headed for downtown Detroit.

The class met its tour guide, named Mama Kuba and gathered in a circle under the glass rotunda of the museum. In the shadows of flags from the African Diaspora — the forced emigration of the people of the African continent through the slave trade — they read the names of prominent African-Americans etched in brass plates framing the rotunda’s floor mural.

Harriet Tubman, Nelson Mandela and Malcolm X were just a few of the names.

Kuba, who worked at the museum for nine years as a guide, explained how race doesn’t exist because Africa was the cradle of civilization and the source of all people on the planet.

“Race is a social construct, for someone to feel on top,” she said. “We all come from the same people. There is no such thing as race.”

The museum’s main exhibit, entitled “And Still We Rise” took students through another journey beginning with the roots of the slave trade in Africa, through the process of traveling to the New World on a replica slave ship, and into the present age through the civil rights movements and other African-American successes.

“What is America?” the introduction video asked. “It is slavery, and it is freedom.”

Williams had explained before the trip that the most intense aspect of the exhibit would be the replica slave ship, complete with wax slave figures and sound effects. At the top of the stairs into the hold — “the belly of the beast” — students hesitated. Kuba, who recognized fear in their hesitation, challenged them to think deeply about the journey.

“It is not to hurt you, but to teach you and make you stronger,” she said. “Why should we learn this?”

“Because we do,” answered Otis Arnold, a senior public health major.

Stepping into the ship’s hold, a dry heat and complete darkness overcame the group. A recording of men crying out for help and women and babies wailing played in the distance. Some students cried out, leaning against the racks of wax slaves bound in chains. Some held onto classmates as they struggled to stand. And some even left the exhibit, overwhelmed with the realistic depiction of what life was like on the ship.

“I had to walk away, I was crying. It was too much,” said Jhane Gaines, a freshman exploratory major. “Just seeing how it was hot, they were laying on each other, they had to poop and pee around each other. I really tried to put myself in that situation. This stuff was real.”

Gaines’ experience was overwhelming and life-changing. She couldn’t imagine being at home and having her family taken and separated by force. After seeing the exhibits, her outlook on African-American history changed.

“I think it changed me. It opened my eyes,” Gaines said. “Before this class, I wasn’t into that black power stuff, like it doesn’t mean nothing to me. I get it, we were slaves, I’m over it. But no. I’m not over it.”

Kenny Jenkins sat quietly by himself after exiting the exhibit. Processing the information, he said, was tough because “when you’re in there there’s so much coming at you, you don’t really know what to think about.”

“At the beginning, I was kind of feeling inspired, just learning more about my history. But toward the slave part, it started to hurt a little bit. Kind of broken in a way. I felt like I went through the same history just by walking through there,” Jenkins said. “I thought going down there, into the belly of the beast, it would be a lot worse, but it was still pretty bad. I think it was the wax statues, but seeing them really realistic. It was scary. It was too real.”

For him, the journey was a roller coaster of emotions.

“It makes me feel empowered because we talked about it in class. All of the people who have went through things, African people have gone through some of the worst things, and we still exist today. We are still rising, even though all of the things we went through,” he said. “We were talking about other civilizations and how they all went through really tough times and kind of died out. But even going through all of the painful things, like slavery, we still came back, and we still have a chance to be empowered.”

Exiting the slave ship and moving through the remaining exhibits, many of the students chose to be optimistic after reading about African-Americans triumphs throughout U.S. history.

A replica of downtown Detroit — complete with a barbershop scene, the Horse Shoe Bar and a Baptist church, along with sections about the Freedom March of 1963 — helped students think more positively about the future.

They were survivors, some said. Their ancestors and relatives endured slavery and triumphed, often with the support of religion and music at their core.

Motown Museum

The class completed its journey listening to and singing the songs of Motown, a company located in downtown Detroit known for its role as a racially integrated record label.

Standing in Studio A, the recording studio at Motown Records, the class marvelled at being in the same spot where black musicians made history. Recording songs that broke more records than many of the prominent white labels of the time, the black musicians of that time broke not only music records, but rewrote black history and dissolved racial barriers as well.

“At Motown, I was so happy,” Gaines said. “It was a turnaround. The creativity of, like, from us not being able to know how to read to us knowing how to do music and make things…and the different ideas that came from a black person in that time period. That wasn’t something that was supposed to happen for us to do. And we did it.”

Contact Matthew Merchant at [email protected].