Kent State professor, student research treatment for rare skin disease

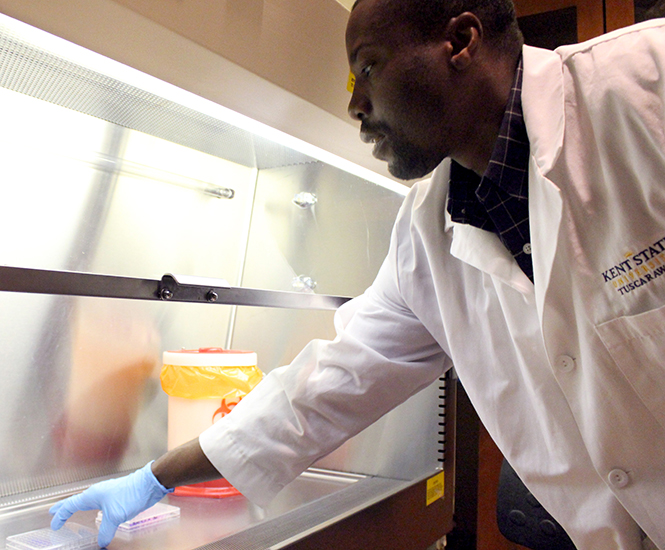

Dr. Engohang transfers resasurin in microplate Wednesday, April 2, 2014.

April 6, 2014

A Kent State professor and undergraduate student are working on a research project to discover a possible new antibiotic to treat a tissue-killing skin disease.

Jean Engohang-Ndong, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Kent State Tuscarawas, and Jean Wilson Mutambuze, a senior biology major at Kent’s main campus, are researching the new treatment for the disease called Buruli ulcer.

Buruli ulcer is a tissue-killing disease that eats away at soft tissue and skin if left untreated. It is caused by bacteria called mycobacterium ulcerans.

“The organism actually produces a chemical that is toxic for skin cells,” Engohang-Ndong said. “Therefore, it causes the necrosis of skin tissue.”

Engohang-Ndong said the mycobacterium ulcerans belongs to the same family as the agent that is responsible for human tuberculosis and leprosy.

Mutambuze said the two antibiotics they are working with are pipeline tuberculosis drugs named BTZ043 and PNU-100480.

“We thought that if these two drugs are showing successful clinical trials at treating mycobacterium tuberculosis, why don’t we use them to try to see if they’re effective at treating mycobacterium ulcerans?” Mutambuze said.

The two researchers started studying the Buruli ulcer antibiotics when they met in 2011.

“I was looking for a project that was interesting, something that would have an immediate impact on people,” Mutambuze said. “Dr. Jean seemed to be making an impact in the community. In addition to doing research and finding cures, he also reached out to physicians who were dealing with these problems in West Africa.”

Engohang-Ndong said he started working on antibiotics when he was a doctorate student in 1999.

“I did work on tuberculosis, and my major interest was to improve the treatment of tuberculosis using what we call second-line drugs,” Engohang-Ndong said. “What I showed when I was a Ph.D. student was that by playing a little bit with the mechanism of action with the drug, we can actually decrease the amount of drug that is needed to kill the microorganism.”

Engohang-Ndong said Buruli ulcer is oftentimes overlooked.

“Buruli ulcer is a neglected disease,” Engohang-Ndong said. “Because it is neglected, there are a lot of cases that go unnoticed because people are just not aware of it — not just the sufferer but also the professionals.”

Engohang-Ndong started a non-profit organization called the International Actions Against Buruli Ulcer, or IAABU, to continue to find a way to defeat the disease.

Mutambuze said the IAABU has the impact on the community that he was looking for.

“It would be nice if studying tuberculosis and mycobacterium tuberculosis would be done congruently with Buruli ulcer because the two are just about the same,” Mutambuze said. “So any investments made with tuberculosis should also be considered for tropical neglected diseases like Buruli ulcer as well.”

For more information on the Buruli ulcer, visit http://buruli.org.

Contact Hannah Reed at [email protected].