The conflict in Syria: A revolution, not a civil war

July 17, 2013

Skip to a section:

Secret factory of the Ahrar Suriyah | Adapting to overcome |

The birth of a democracy | The fighting | The cost of war

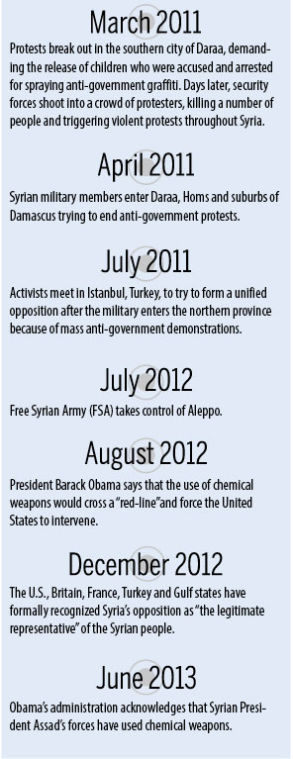

As the Syrian Revolution enters into its third year and the death toll rises to around 120,000, the international community has still done little to help stabilize the region. President Obama’s administration has acknowledged that the Syrian government had crossed the “red line” with the use of chemical weapons. The U.S. has now pledged lethal aid, in the form of small arms, rocket-propelled grenades and anti-tank missiles, to certain rebel groups fighting in Syria.

“We wish we could tell the difference between the colored lines. We are fed up with the red lines, yellow lines and green lines,” said Abu Hassam, a retired Syrian Army officer who now teaches military tactics at a small Free Syrian Army (FSA) squad, referring to President Obama’s declaration in June that Bashar al-Assad’s regime had crossed a red line. “The big players [of the world] are saying much but doing little.”

Hassam is not the only Syrian who feels this way. At this point in the revolution, many Syrians, fighters and civilians, have lost hope that the international community will step in to provide the aid they need. The international community’s lack of intervention leads many Syrians to believe that the world is “condoning” al-Assad’s actions against his people.

“If they do not want to help [the fighters] at least help the [civilians] here,” said Hussein, an English teacher who used to live in London. He now leads a small platoon of fighters a little north of Aleppo in Hritan. “They did not choose to be in the middle of this.”

That thought is shared throughout the military community in the areas around Aleppo. Many of the leaders are confident that they can win the revolution without international aid, though it will take longer.

“We [FSA] are advancing everyday. We will win,” said Ahmad Afash, the commander of Ahrar Suriya brigade. His brigade is arguably the strongest brigade in the area. “We [will] fight until our last drop of blood.”

Afash wasn’t always a soldier. Before the revolution he was a wealthy real estate broker. When the bands of rebels first stood up to the government forces, they were using hunting rifles and shotguns. It became apparent that those weapons would not suffice. Using the money made as a broker, Afash bought military-grade weapons and armed a small group of fighters.

In the early days of the brigade they were able to win major victories in the area, including a large regime military checkpoint in Anadan, about four miles north of Aleppo. From this victory they were able to acquire assault rifles, ammunition and a few armored vehicles, such as the Russian-made T-72 tank and BMPs, both armored personnel carriers.

His brigade is now in the thousands. Many of them do not receive salaries and those who do are receiving very little.

Even as one of the stronger and more organized brigades in the area, they have received little help to get where they are today and, like most units, are struggling to get the arms they need to end the conflict.

“We are depending on what we are manufacturing, what we are taking from the regime and God,” Afash said. “We were waiting for support, for anyone to support us.”

That support never came, but that did not stop his brigade from thriving on the battlefield.

Secret factory of the Ahrar Suriyah

Underground at an undisclosed location in the northern countryside of Syria, there is a factory run by six brothers and a handful of others. It’s a factory so secret that the thousands of fighters they build arms for know nothing of its existence. Here these men — some teenagers — manufacture and develop weapons for the Ahrar Suriyah.

Four of these six brothers left their jobs as foremen in Beirut; none of them had made explosives like the grenades and mortars that they now produce. Mohammed, 37, said they started off with less advanced weaponry, creating cannon-like weapons to combat the regime’s armor. But as they learned the ins and outs of manufacturing weapons, they began producing more traditional rounds.

After receiving the forged mortar casings, the workers begin hand-making each part that is needed for a functioning shell, from the tail fins and innards of the mortar to the more advanced fuses.

Using outdated machines and recycled material, this facility is able to produce 50 mortar shells, ranging from 40 mm to 120 mm, in 14 hours. It also produces about 1000 grenades a day, made using old-pipe, salvaged explosives and fuses that must be lit. Mohammed says they could produce much more if they could get their hands on newer machines, but they make due with what they have.

Abu Abdul, 30, stands in a corner of the facility surrounded by scraps of metal, gutted fired extinguishers and other materials they will use to develop new weapons to combat the advanced weaponry of the regime. He slides his welder’s shield down and begins to work on one of the factories newer projects, rockets. At this stage in the development the rockets look like something you would see in a cartoon: a long cylinder, with bent metal triangles as fins and a comical-looking cone at the top. This is just the beginning though; they hope to develop a guidance system for these weapons.

One of the biggest thorns in the FSA’s side has been the tanks and other armored vehicles that the regime uses ruthlessly against them. Fighters are forced to use mortars to combat the enemy tanks, but they lack the technology to accurately aim the mortars, making it very hard to hit a group of tanks from even a mile away.

The workers are doing what they do best though and overcoming a challenge. They have recently started to develop anti-tank mines, or improvised explosive devises. According to an officer in the Ahrar Suriyah, if these mines are used properly, then one is strong enough to destroy two tanks. There is a downfall to this method: the fighter triggering the explosive must be close enough to the tank to send the electrical charge down the wire to ignite the blasting cap.

As the revolution continues, with no sign of the advanced weapons they had hoped the west would provide them, the brothers hope to produce 200 mm mortar shells, grenades and even a device that can only be described as a hand-held grenade launcher made from scrap and using recycled machine gun casings.

Building missiles and mortars is one thing, but how do the rebels accurately aim them to minimize civilian casualties and maximize the small amount of ammunition that they have? Tawfik, a math teacher living in Aleppo, has come up with a method of directing weapons to a target using only Google Earth and a compass. His method works so well that he says about 90 percent of the weapons launched using his method hit their intended target.

Tawfik starts off by scouting locations to fire from and targets on Google Earth. From Google Earth, rebels can get the longitude and the latitude of the target. Next, they go to the area they plan to launch from and make sure it is safe. From here, they can use an electronic compass to determine the angle of the mortar tube or missile platform. There are other factors to take in like wind speed and quality of the weapon they are using. Some local manufacturers have not mastered the process of creating a mortar or rocket, leaving room for errors in their design and making it harder for Tawfik to use his targeting method.

Tawfik has taught other fighters his method and he says that it is simple enough that most fighters pick it up after seeing it done once, and those who don’t just take a few more extra lessons.

Tawfik said the weapons they launch using this method are anti-personnel, meaning they are used to attack people rather than vehicles. They lack the punch needed to penetrate the thick armor of a tank. According to Tawfik, the FSA has chemists and physicists working on a way to develop more deadly explosives, like C4, to increase the destructive power of their missiles and take away one of the few advantages the regime has over them.

The people of Aleppo have not only stepped up as a fighting force but have also set up a governing body. At first, villages set up councils that were established by a popular consensus. At the beginning of the revolution, some of these councils were funded by military brigades. They would organize public services like garbage removal, sewage issues and fuel production. A council in Qubtan Eljabal is even urging its young people to do volunteer work around the city. A lot of this work is about maintaining the city and beautifying it after months of neglect.

“Fighters should fight and civilians should [help out with problems on the home front],” one of the men in charge of organizing the volunteers said.

“Before the revolutions there was nothing like this, now you can find it everywhere,” Muhammad Ali Ahmad, the Qubtan Eljabal council head, said. “Although we don’t have enough financial aid we are trying to do the most we can.”

Even in the city of Aleppo, where fighting occurs daily, garbage fills the street and walking down the wrong street could mean death, the FSA has managed to provide assistance to the civilians trapped there. But with money and food scarce, and ammunition even more rare, the people and fighters have been forced to sell their possessions to buy the things they need. For example, fighters must pay 185 liras (one U.S. dollar) for one round of AK-47 ammunition. It costs around 40 cents per round in the U.S.

Eventually, the village councils selected representatives to take part in something bigger. They created a governing body to organize the people living in the free part of Aleppo and provide the things a government would normally provide. Every village chose two or three representatives, and those 243 people convened in Gaziantep, Turkey, to vote for the municipality council of Aleppo.

Twenty-nine council members were elected and from there, and those members voted for the president and vice-president of the committee. Then, the governing council hired employees and set up 10 offices in charge of organizing different areas of the newly free areas of Aleppo.

“Our responsibility is to organize services and try to provide for our society,” said Ahmed Eido, the secretary general of Aleppo Municipality Council. “We are in a difficult stage. We lack financial support.”

The council is operating on a very small budget — higher-ranking members of the council work for as little as $100 per month. Their six-month budget is equivalent to what the regime government’s budget was for one day.

The council is hoping for outside support. They have met with Turkish and Syrian businessmen hoping to receive that support in the form of loans.

They are also looking for ways to support themselves. The council has been stocking wheat and selling bread. They are planning on building two bakeries in the area that will sell goods made with government wheat. The income from these bakeries will be split with local councils and will allow them both to finance future projects and rebuild Sheikh Najjar, the industrial city just northeast of Aleppo.

Sheikh Najjar has about 2,500 factories within its limits. These factories produce things like textiles, medicines, petrol and types of food. Only about 1,000 of these factories are currently producing goods. There are many problems that need to be resolved in the industrial city, such as electrical malfunctions, lack of raw materials needed to produce their goods and lack of markets to sell them.

The municipality council of Aleppo is convinced that if the industrial city gets up and running then the economy of Aleppo and surrounding countryside will thrive once again.

The revolution still has one obstacle to overcome before any of this can come to fruition: defeating al-Assad, his regime and its foreign supporters.

The sound of gunfire, warplanes and artillery echo throughout the night sky in northern Syria. The regime’s superior airpower forces the FSA, and groups like it, to wait for the cover of night to launch their attacks. Outgunned, the rebels set up snipers to watch their enemies during the day, hoping to catch a few off-guard to even the odds.

The lack of advanced weaponry hasn’t stopped the rebels from advancing. In the past weeks, rebels have made progress taking back neighborhoods in Aleppo and increasing the pressure on regime troops under siege at Mingh military airport.

Multiple rebel groups, such as Al-Nusfra, the Squadrons of Ilbez and Ahrah Suriya, have come together to work as one fighting force to take most of the compound. They estimate about 150 to 200 regime soldiers are left holding that part of the compound on the west side of the airport. They are equipped with at least three functioning Russian T-72 tanks, armored personnel carriers and assorted small arms. The besieged troops only receive supplies from regime aircraft that are forced to drop them in via parachute from high altitudes. This method has proved more helpful to the rebel fighters surrounding the compound than the regime soldiers inside. The leader of the Squadrons of Ibez reports that they receive about two-thirds of the supplies dropped.

The armor inside the compound and the constant threat of air strikes against the rebels has drawn out the battle for Mingh military airport for about eight months. The rebels here have only RPGs, heavy machine guns and assault rifles, none of which are able to take out a tank from a distance. That does not stop them from trying to advance. At night, they sneak into the compound and attempt to get close enough to disable the tanks with RPGs, but have been unsuccessful. On June 23, 2013, the rebel fighters surrounding the airfield loaded an armored personnel carrier with explosives, reportedly up to four tons, and remotely controlled the vehicle towards the area held by regime troops. The attack failed and the explosion was felt from about 10 miles away, but an organized attack like this illustrates the resourcefulness of the rebel fighters and their determination to defeat the regime.

The revolution has touched everyone in the country in some way, from the child who lost a father, the military leader who lost his two brothers and 36 of his cousins, to the old man whose sons paid the ultimate price during the fight for their village’s freedom.

Helal, a frail-looking, elderly man suffering from a heart condition sits on a stone. He is wearing traditional Syrian garb, with a red scarf around his head. He takes a sip out of his tea. Within arms reach, hiding behind a curtain is an AK-47. Because of his age and his heart condition, he is unable to fight, but he keeps his rifle near him, hoping that the regime will return to Benoun, an area under FSA control, so he can have his revenge.

“[The regime] is a bunch of criminals, they chose to fight us. We are only defending our village and ourselves,” Helal said. “When we win against the regime, I will feel like I have my children with me again.

As the revolution continues and the first few nails are hammered into the regime’s coffin, a vibrantly painted phrase can be seen painted on walls around northern Syria. This phrase describes the feelings of the Syrians people like only they can:

“It’s important to be free, but it is more important to know what freedom means.”

Contact Coty Giannelli at [email protected].