Censorship is unlikely in University Libraries

June 19, 2012

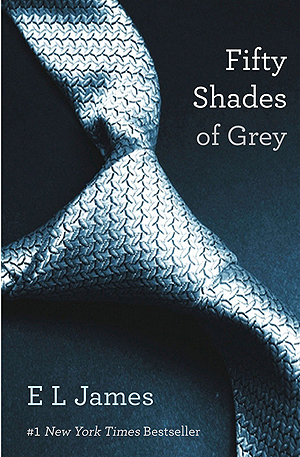

The New York Times bestseller “Fifty Shades of Grey” is the most recent book to fall victim to censorship in a handful of libraries throughout the United States, but it is unlikely any books will be censored by Kent State University Libraries.

Barbara Schloman, associate dean of University Libraries, said academic libraries do not ban or censor books, and Cindy Kristof, head of Access Services for University Libraries, said there has never been a book censored by University Libraries before.

“University Libraries has a collection development policy which lays out the collection parameters that are designed to guide the acquisition of materials to support university research and teaching,” Schloman said.

Censorship is more likely to be seen in public libraries because the environment is very different from an academic library.

“Public libraries have a much different environment,” Schloman said. “They are developing their collections to address the various needs and interests within the community.”

While academic libraries build their collections over time, public libraries change theirs according to demand, Kristof said.

Censorship is also more common in public libraries because of differences in audience.

While collegiate libraries have to answer to university administration and the needs of the university’s community, public libraries are accountable to their library boards and to members of the community as they go for levy support, Schloman said.

“Public libraries are more likely to face censorship because of the communities they serve,” Kristof said. “Members of the community are likely to want their library to conform to what they perceive as community standards.”

The process of banning a book is simple, and anyone can challenge a book. First, someone files a complaint with the library and specifies in the complaint what information is being considered offensive. Once the complaint is filed, a committee will review the challenged material to determine if the claim is substantial. Depending on what the committee decides, the book is either removed from the library or kept on the shelves.

The fact that there is a process for banning books and other materials does not mean the American Library Association approves of censorship.

“The American Library Association and the library profession value both intellectual freedom and the freedom to read,” Schloman said.

Kristof said she views herself as someone who wants all points of view expressed and available for study, even if she doesn’t agree with them, but there is no simple answer when it comes to censorship.

“There are certain materials, such as neo-Nazi propaganda, that my gut instinct finds repulsive, and I don’t think deserves a place on our shelves,” Kristof said. “However, what if we have a sociologist doing a study of this sort of propaganda?”

An emerging problem right now with censorship deals with electronic content, Kristof noted. Libraries choosing to license electronic content instead of purchasing the print materials are essentially renting the content, and once the license is up, the library doesn’t have access to it anymore, she said.

“‘Born digital’ materials could potentially be changed or edited, and if you don’t own the copy, how will you know?” Kristof said. “You can see how in the world of licensing, censorship could be accomplished more subtly and easily.”

Contact Erin Vanjo at [email protected].