Kent State student: I was there

September 9, 2011

It took me a moment to process her words. Then it dawned on me: If it was an earthquake, the last place on earth I wanted to be was on the floor 16 of a building.

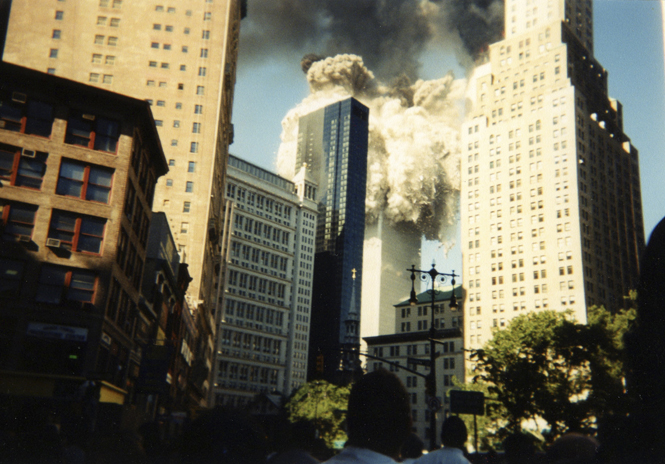

I turned on my TV to see if the news had any answers. I remember staring at the screen for a moment before bolting out of my room into the lounge. I pressed my face up against the glass and stared at the two towers burning.

I remember running back to my room and shaking Alex from her sleep. I told her that the World Trade Center was on fire, and she had to get up now. I don’t really remember getting dressed or heading downstairs.

When we approached City Hall Park, hundreds of people were standing in the street, staring up. We stood there for a moment with the crowd, and I decided I needed to get a camera.

I ran over to Duane Reade pharmacy across the park. All of the regular disposable cameras were already sold out. I guess a lot of other people had the same idea.

There was an underwater camera left. I bought it and ran back out onto the street. A few police officers were trying to keep people back, preventing them from impeding the towers’ evacuations.

But I don’t think anyone expected the towers to fall.

I walked out to the tip of City Hall Park and started to take some pictures. I could hear people in the crowd talking about what happened.

No one seemed to know why it happened or who was responsible. We all stood there and stared for what felt like a long time, but it was probably less than 30 minutes.

I remember hearing a rumble coming from the direction of the twin towers. It sounded like a loud creaking noise at first. People started to scream.

The south tower started to collapse that morning a little before 10 a.m. I could see the top of the building tilt slightly and then it started to come down.

I stood there taking photos while everyone around me ran away. It felt so surreal to me. I kept wondering when I would see a giant monster creep around the corner like in the movies. I couldn’t process that this was reality.

I remember Alex tugging on my arm and screaming at me that we had to go. The crowd was rushing past us. People were looking over their shoulders as they ran from the giant cloud of dust and debris that was now weaving its way through the city streets. I stood there, staring at it.

Alex was tugging harder. She made it quite clear that staying put was no longer an option. I felt her jerk my arm, and I began running.

We ran down the street and back into the lobby of our dorm. Almost immediately after we got inside, a dark cloud rushed past the entrance and the sky turned black.

I remember thinking how strange it was that it was dark outside in the middle of the morning.

We stood there stunned for a few moments. Students and pedestrians who had taken shelter inside the building all had the same two questions on their mind: Who could have done this, and what do we do now?

Most people started to cry.

After what seemed like a short time, the building shook and lights flickered. I could hear a loud rumbling and the sky went dark again. It sounded like everyone in the lobby screamed at the same time.

I began looking around and saw a guy and a girl just holding each other, sobbing hysterically.

It still felt so unreal to me – like I was having an out of body experience. It’s like I was watching the events of my own life from a sideline. I knew I was there, in a lobby in downtown Manhattan, but it didn’t feel like I was anywhere.

I walked around outside afterward. The streets were covered with gray ash and debris. There were pages from books, briefcases and shoes littered throughout the streets. The shoes were the hardest to look at.

I kept telling myself that if I lost a shoe running, I wouldn’t stop to find it. I wanted to believe the people who put on those shoes were still alive.

I picked up part of a manual. I flipped through the few pages, and I couldn’t believe it was actually in my hands. I was holding part of book that had been up in the towers only hours earlier. I still couldn’t shake the feeling that I was dreaming.

Eventually, I made my way to a friend’s house in Brooklyn for the night. My parents lived about an hour north of the city, and transportation from Manhattan was chaotic to say the least. I spent the rest of the week with my family, glued to the television like many other Americans.

It was strange to go back to classes. It felt awkward just jumping back into a routine when so much was obviously different.

Lower Manhattan was closed off to cars, and the police setup checkpoints where you had to prove you had business below Canal Street. The Trinity Church across from City Hall Park was covered with missing person fliers, candles and memorials.

I remember people cried a lot in the weeks after. Everyone you met would share their story about where they were and if they knew anyone who died or was still missing.

I still felt numb about the attacks, and I felt numb about everything else in my life. Weeks passed, and I still couldn’t shake the feeling I was dreaming. I felt like I was going crazy, or perhaps I had always been crazy and just never knew it.

One night in early October, I found myself out wandering the streets of lower Manhattan alone.

Like many nights since the attacks, I couldn’t sleep. I walked down to the makeshift barricades on Vesey Street. I don’t know what got into me, but I slipped through a crack in the barricade and made my way down to ground zero.

I stood in the shadows across from the entrance to the Borders that used to stand at the edge of the trade center. After a few moments, I stepped out to the edge of the sidewalk.

The cop approached me from across the street. I hadn’t seen him, and I don’t think he saw me until I stepped into the light cast by the floodlights.

We both stood there for a few moments, not saying anything. I pointed across the street and said there used to be a Borders on that corner. I told him there was an escalator right past the doors that would take you down to the mall and there was a Lens Crafters down there just past the escalator where I went for my checkups. I told him that a few days before the attack, they had called me to pick up my contact lens. I was going to go get them that morning.

I was supposed to take that escalator down there after a run I was supposed to take on the West Side Highway, but I had overslept. When my alarm went off, I ignored it and rolled over. I figured I’d get my contacts after class.

I started to tell him how I woke up when my bed shook, but my voice cracked. I could feel the tears welling up in my eyes. I’d been trying to cry for weeks, but now, in front of a complete stranger, I fought them back. I tried to keep talking while squeezing my eyes shut, but the first of thousands of tiny drops starting pouring down my face.

After a few minutes, the tears subsided, and I just felt embarrassed. I figured I’d made a complete ass of myself and probably looked like one too with my red, tear-stained face.

The cop said to take all the time I needed. When I was ready to go, he’d walk me out. He said I could have been arrested for sneaking past the barricades, but he’d make sure I got to the other side safely.

When I stepped through the barrier, it felt I was waking up from a long, strange dream. Things didn’t feel so hazy anymore.

In the years since Sept. 11, I’ve learned that dissociation is a common response to what we perceive as a serious threat. We “go someplace else” because where we are feels too frightening to stay.

My reaction was common and perfectly normal given the circumstances.

But at the time, I thought my lack of emotion made me some kind of heartless monster. The most important lesson I learned is that when tragedy strikes on any scale, there is no correct way to feel about it.

We all grieve in our own way.

Contact Anna Staver at [email protected].